Issue: 3/2021

Background to Freedom of Press in India

Discussions about freedom of the media in India often revolve around controlling free speech. The freedom to express opinions is essential for the fourth pillar of a democracy. As emphasised by UN Secretary-General António Guterres: “No democracy can function without press freedom – the cornerstone of trust between people and their institutions.”

Indian Nobel Prize laureate Rabindranath Tagore expresses it as follows:

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free; […]

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

However, his poem seems to have lost all of its meaning in today’s India. The country is far removed from this longed-for “heaven of freedom”. The state of the media in India is characterised by police violence against journalists, guerrilla attacks, and reprisals by criminal groups and corrupt politicians. The high number of murdered journalists and editors highlights the dangers inherent in their work. The freedom of expression protected in Germany by Article 5 (1), line 1 of the Basic Law finds its counterpart in Article 19 (1) of the Indian Constitution. It is a cornerstone of every democracy. All Indian citizens have the right to freely express their opinions without hindrance, and thus the same applies to journalists and the press. However, the Indian Constitution does not contain a specific guarantee of freedom of press similar to that found in Article 5 (1), line 2 of Germany’s Basic Law and an absence of censorship. In India, Article 19 (2) gives the government the right to impose “reasonable restrictions” on the exercise of these freedoms.

Although there is still no consensus on what constitutes “reasonable” restrictions, the increasing criminalisation of critical reporting has to some extent been countered by a Supreme Court ruling in favour of freedom of press. Article 19 (2) of the Indian Constitution sets out three conditions for restricting freedom of expression and freedom of press:

1. The restrictions are subject to a legal provision.

2. They must be in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency, or morality, or related to contempt of parliament or the court, defamation, or incitement to an offence.

3. They must be proportionate.

Freedom of the media encompasses the traditional print media, radio, and television but also other formats such as theatre, cartoons, graffiti, film, over-the-top (OTT) platforms, blogs, and various social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. A new medium that is emerging, particularly in India, is stand-up comedy. Any medium can be the target of government restrictions and private influence in order to suppress opinions or steer them in a particular direction.

How Is Freedom of the Media Restricted?

In recent years, efforts to stifle critical reporting and prevent participation in protests have increased. The government and police have exploited new constraints and made extensive use of old restrictions, while the private sector is also able to exert a major influence. The latter is generally done with a view to promoting rather than suppressing a particular opinion.

Criticising the government or its policies does not make someone a terrorist or a criminal. The legal validity of this obvious fact has to be constantly established in individual cases, even going as far as the Indian Supreme Court. A country cannot stifle its citizens’ freedom of expression by involving them in criminal proceedings for simply expressing an opinion.

The sedition law (section 124A of the Indian Penal Code) was introduced by the British colonial administration in 1870 to prevent Indians from expressing their opinions. It was abolished in Britain back in the 1920s, but was retained in the colonies and, even following independence, extensively exploited by successive Indian governments, mainly as a way of silencing their critics. In 1922 – still during the colonial era – Mahatma Gandhi was sentenced to six years imprisonment under this law for calling on people to resist the British administration.

More recently, under the coalition government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), annual cases have almost doubled compared to figures under the previous Congress Party administration. The Supreme Court of India has therefore rightly ruled that journalists cannot be detained for sedition merely for criticising the government. Despite the courts having repeatedly taken corrective action in such cases, this has had little impact on police practices, which are presumably intended to at least act as a deterrent. The law is now being scrutinised by India’s Supreme Court and examined for its compatibility with the Constitution. Remarks made by Chief Justice N.V. Ramana left no doubt that “the Supreme Court is prima facie convinced that sedition is being misused by the authorities to trample upon citizens’ fundamental rights of free speech and liberty”.

Ongoing Criminalisation and Attacks on Freedom of the Media

Freedom of expression has also been effectively curtailed by the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) of 2019. The act – introduced to better combat terrorism – expands the previous definition of “terrorist” and the powers of law enforcement officers. This is problematic: according to experts, this law does not allow any kind of dissenting opinions, since it already criminalises mere thoughts that supposedly cause discontent. As a result, it criminalises political protests against the government. In this respect, it constitutes an assault on citizens’ rights to freedom of speech. In addition, those arrested under UAPA can be detained for up to 180 days without a charge sheet being filed. This may also violate Article 21 of the Indian Constitution (protection of life and personal liberty).

In mid-June 2021, three student activists who had spent more than a year in detention awaiting trial for “terrorist activities” for having organised demonstrations were finally released on bail – an example of how the State can abuse counter-terrorism tools to suppress freedom of speech. The Delhi High Court rightly maintained: “It seems, that in its anxiety to suppress dissent, in the mind of the state, the line between the constitutionally guaranteed right to protest and terrorist activity seems to be getting somewhat blurred. If this mindset gains traction, it would be a sad day for democracy.” Nevertheless, the instrument is likely to succeed as a deterrent, as the amended law will be used to suppress dissent through intimidation. This threatens the very existence of public debate, freedom of speech and press. A number of people have been detained for expressing their views under suspicion of terrorism.

Another instrument is set out in Section 144 of the Indian Code of Criminal Procedure. In this way, too, the freedom of expression can be suppressed, at least temporarily. However, this implies the existence of an urgent, specific threat to public order. Mere probability or possibility is not sufficient for this purpose. Given that case law has clarified the application only in the case of incitement to commit a crime, this instrument no longer plays a major role here. However, as will be discussed later, it is used as a legal basis for the frequent internet shutdowns occurring in India. Another form of restriction is blocking news channels and portals in the event of undesirable reporting. In 2020, India blocked AsiaNet News and MediaOne TV for reporting on the unrest in Delhi (farmers protesting new farm laws).

Attacks on Journalists

Today, Indian journalists are regularly charged with sedition or disturbing public order. They are charged in the name of national integrity – especially when criticising the government – and have to face criminal proceedings. They are often decried as being anti-national. On 3 July 2020, the journalist Patricia Mukhim, an editor at Northeast India’s Shillong Times, wrote a Facebook post condemning the attack on five youths by a group of masked men. A “first information report” was filed against her for allegedly creating communal disharmony. Her case went as far as the Indian Supreme Court, which ruled that her post “cannot by any stretch of imagination be considered ‘hate speech’”.

Journalists who voice criticism face a growing risk of physical assault or even death. Some 200 serious attacks on journalists were reported between 2014 and 2019, with 36 occurring in 2019, mainly clustered around the protests in Delhi. Journalists were killed in 40 of these cases, 21 of which were proven to be related to their work, particularly as investigative journalists. Yet these offences rarely result in prosecution, let alone conviction. Journalists regularly find themselves the target of angry mobs, supporters of religious sects, political parties, student groups, security agencies, criminal gangs, and local mafia groups. However, journalists have also been murdered in the past for exposing illegal economic activities, such as alcohol smuggling or the illicit extraction of mineral resources. In any event, killing journalists because of their work must surely be considered the ultimate form of censorship.

Restrictions on Artists and Cultural Workers

Four years ago, the film “Padmaavat” and more recently the web series “Tandav” attracted the attention of Hindu groups and Rajput caste organisations; the core constituency of India’s ruling parties. Protests escalated into vandalism and threats against the filmmakers and cast. In both cases, the filmmakers were forced to make compromises, such as changing the title to avoid confusion with a historical figure. The film “Bhobishyoter Bhoot” (2019), a satirical comedy in Bengali, was removed from several theatres in Kolkata immediately following its release. The Supreme Court directed the West Bengal government to pay compensation to the film’s producer for restricting its screening. The Court also imposed a fine on the government led by Mamata Banerjee (of the All India Trinamool Congress party) stating that “free speech cannot be gagged for fear of the mob”. However, it is not only filmmakers but also cartoonists who sometimes face the wrath of the government if they dare to criticise it or its policies. In April 2021, Ambikesh Mahapatra, a chemistry professor, was arrested and detained overnight for forwarding a cartoon to friends that mocked the West Bengali Prime Minister Banerjee.

On 4 April 2021, the Indian government ordered the abolition of the Film Certificate Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), which heard appeals from filmmakers seeking certification for their films. The abolition means that filmmakers will now have to approach the High Court if they want to challenge a particular certification or its denial by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). In India, all films must have a CBFC certificate prior to being broadcast on TV or screened in public. The CBFC can also refuse to certify a film. In the past, it was often the case that filmmakers and producers were unhappy about the CBFC’s certification or denial, but they had the option of appealing to the FCAT. And in many cases, the FCAToverturned the decision.

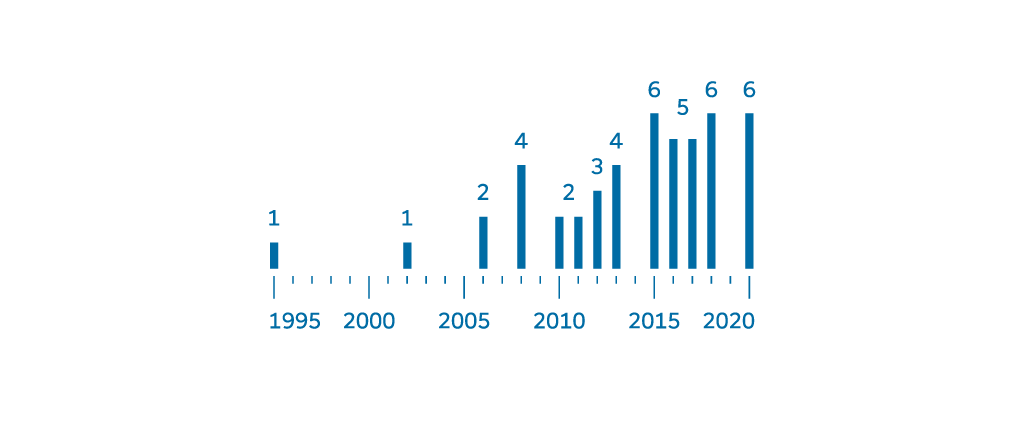

Fig. 1: Number of Journalists Killed in India per Year 1995–2020

Source: Own illustration based on UNESCO 2021: UNESCO observatory of killed journalists – India, in: https://bit.ly/3sGXd1A [24 Aug 2021].

The film “Haraamkhor” (2015) was denied CBFC certification as it depicted the relationship between a teacher and a young female student. The FCAT cleared the film on the grounds that it could be used for “furthering a social message and warning girls to be aware of their rights”. The film “Lipstick Under My Burkha” (2016) was denied certification in 2017. Director Alankrita Shrivastava appealed to the FCAT, after whose verdict some scenes were cut, and the film was released with an A certificate (for adults only). Thus, the main function of the FCAT was to hear the complaints of filmmakers applying for certification who were aggrieved by the CBFC’s decision. Numerous filmmakers, including the award-winning Vishal Bhardwaj, have voiced their concern following the abolition of the FCAT and taken to social media to protest the decision.

Fairly recently, the police also arrested stand-up comedian Munawar Faruqui for allegedly making jokes about Hindu gods. Meanwhile, in Goa, members of the rock band Dastaan LIVE were acquitted of charges of “hurting religious sentiments” while performing at an arts festival. The court noted that when it comes to the offence of hurting religious sentiments, the police should be more sensitive as freedom of speech and expression is at stake.

Abuse of Freedom of Speech

In India, media houses are sometimes accused of being corrupted and pro-government. This is illustrated by recent coverage of the COVID pandemic. According to German media reports, last year the government pressured the owners of 15 daily newspapers to report positively on its handling of the pandemic. These media outlets failed in their duty to inform, which led to problems being swept under the carpet rather than solutions being found. However, when the pandemic hit India on a truly horrific scale, the facts could no longer be concealed.

The influence of large corporations, which significantly impact on media outlets’ income through their advertising, also leads to restrictions on freedom of expression. Despite the huge number of media outlets in India, there is a high degree of market concentration. The Indian government is their largest advertising customer, which means that – together with its allies in the private sector – it has a major influence on their revenues. India’s richest businessman, Mukesh Ambani, a close ally of Prime Minister Modi, has “backed” five media companies with loans. To a great extent, large-scale media corporations determine what is published. However, “paid news” interferes with freedom of press and violates ethical principles.

Another problem in India is the phenomenon of the media proclaiming the guilt of the accused before the court pronounces its verdict, known as “trial by media”. Such reporting by news outlets hinders investigations essential for the justice system and permanently damages the victim’s reputation. Although the press is obliged to report on cases of public interest, before publishing they must carefully examine whether the article or statement crosses the boundaries of freedom of press. It is easy to cross the line and descend into trial by media. The suicide of actor Sushant Singh Rajput became the subject of such a trial. The press destroyed the reputation of the late actor’s partner, actress Rhea Chakraborty. She found herself the target of a vicious hate campaign propagated by high-profile journalists and social media trolls that pronounced her guilty of all kinds of crimes. In the murder case of 13-year-old girl Aarushi Talwar, the media had declared who was and was not guilty even before the actual trial began. It later turned out that the domestic worker, already “convicted” of murder by the press, was not the perpetrator. Yet there are also a few positive cases to report. In the past, the fourth pillar of Indian democracy has proven to be a potent weapon in promoting victims’ interests in some notable murder cases.

Control of the Internet and Electronic Media

Today, with an estimated 630 million users, the internet is one of the main methods of disseminating information in India and is therefore covered by the right to freedom of expression guaranteed in Article 19 (1) (a) of the Constitution.

India, too, is aware of how modern terrorists are exploiting these new cross-border opportunities for their own ends. A temporary ban on the internet may be an appropriate way of curbing terrorism when the web is used to incite violence. Nevertheless, recent years have seen internet shutdowns become a widespread phenomenon in India on the grounds of curbing fake news and terrorism. India has experienced more internet shutdowns than anywhere else in the world and represented 70 per cent of global shutdowns in 2020 (109 known cases). It also came top of this ranking in 2018 and 2019. As in previous years, most cases were recorded in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Faced with these alarming numbers, the question arises: to what extent do these shutdowns undermine citizens’ constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression?

The Indian Telegraph (IT) Act of 1885 empowers the government in Section 5 (2) to block the transmission of messages in the interests of maintaining public safety or in an emergency. Following a Supreme Court intervention over a five-month long shutdown on 10 January 2020, the Modi government finally decreed that internet shutdowns can last no longer than 15 days. Section 69A of the IT Act 2000 empowers the Indian government to block online content and arrest offenders. Originally intended to protect democracy, this instrument now seems to be used more as a tool to contain the media’s watchdog role.

In mid-June 2021, the Indian press reported that the Indian delegation at the recent G7 meeting had succeeded in amending the communiqué to remove criticism of Indian internet shutdowns and to place national security above individual freedoms. India’s Minister of External Affairs, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, stressed that public safety arguments ought to be prioritised when designing communication flows.

Work on the internet is (still) relatively free of regulation and censorship, which gives content creators the intellectual freedom to experiment without fear of being censored. OTT platforms have given their creative ideas a new lease of life. These relatively new platforms are free from the accepted moral standards prevailing in the largely conservative India. What is more, films released on an OTT platform do not require a licence from the Central Board of Film Certification. However, the regulation of content on OTT is of fundamental importance, not least to guarantee a level playing field with traditional – regulated – media and to take effective action against phenomena such as hate speech and fake news. In 2019, the Indian Supreme Court noted in the case of Facebook vs. Union of India that the misuse of social media had reached dangerous levels and urged the government to develop guidelines to address the issue.

It was now a matter of creating an appropriate framework that balanced freedom of expression with the necessary restrictions for maintaining law and order. The Supreme Court also directed the central government to take responsibility for the digital content presented on these media channels. The Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI), the body representing OTT platforms, had previously proposed a voluntary model for self-regulation. However, the government rejected this proposal and issued its own Guidelines for Intermediaries and Digital Media Ethics Code Rules in 2021. These are intended to address people’s concerns while removing any misconceptions about restrictions on creativity and freedom of expression. The law regulates OTT platforms by requiring them to comply with the laws of the country in which they broadcast. These platforms are also required to set up a mandatory complaints procedure. Considering the political climate previously described here, the fear that an interpretation of these rules could get out of hand and result in more restrictions not only for the creativity of out-of-the-box content, but also for journalistic freedom, is probably justified.

There have been clashes ever since the Indian government began regulating social media channels such as WhatsApp and Twitter. For example, if ordered to do so by a court or the government, social media companies have to disclose who is the author of specific posts. The government can also demand the extensive blocking of tweets or entire accounts. According to critics, what was striking is that this related to media criticism of the government’s management of the pandemic and the highlighting of certain tweets by ruling BJP politicians as being manipulative. This has fuelled the debate about the limits of social media freedom, with numerous court cases now pending. One Indian response to the debate is to create a rival app to Twitter (Koo), which welcomes the government’s “user-friendly rules” and requires foreign companies to comply with them too.

Conclusion

Indian journalists merely enjoy the general right to freedom of expression that applies to all Indians under the Constitutional Article 19. Freedom of press is not regulated by constitutional law. A constitutional amendment to give freedom of press a stronger constitutional status is not expected in the foreseeable future. However, clearer media regulations should be considered at the level of simple legislation in order to protect freedom of press. The focus should not only be on the traditional media, but also on the digital sphere and future advances in communication technology above all.

Internet shutdowns are now time-limited by order of the Supreme Court but are still to be expected in future. Having said that, the negative impact on the right of citizens and journalists to communicate – and thus the harm to democratic principles – could at least be mitigated if the government did not constantly resort to total shutdowns. It may also be possible to achieve the intended security outcomes through less draconian measures according to the principle of proportionality. An example is the proposal not to shut down the network completely in such situations, but to restrict technical ability to send messages. Shifting from 4G to 2G connectivity would make it impossible to share videos or audios inciting violence, but the population would still retain this vital means of communication.

When journalists are attacked, one should expect the government and particularly the security forces to take a more proactive approach to protecting them. Monitoring bodies could be involved in the judicial processing of offences against journalists in order to prevent it foundering. A good start would be if executive authorities could show more restraint in the face of criticism. Academics, journalists, even entire media outlets have been repeatedly labelled as anti-national, hatemongers, or urban Naxalites (a Maoist-influenced guerrilla movement). All over the world, it is normal for people to have different views of government policies, however. The fact that these are allowed to be voiced and often lead to improvements in these policies, is one of the hallmarks of a democracy. If this is prevented, democracy itself is ultimately endangered.

The steady decline of India’s ranking regarding the quality of freedoms, including freedom of press, has little to do with Western bias. It is a consequence of the measures outlined or lack of action and is also perceived as such in India. As a result, complaining about the rankings will do little to change the situation. Instead, what is needed is a proactive approach or forbearance, as described above. If this is pursued, we can expect to see improvements to freedom of press in India. The fact this is likely to improve its ratings and rankings is a secondary effect.

– translated from German –

Prasanta Paul, a student at the Statesman Print Journalism School, Kolkata, class of 2020 – 2021, assisted with the preparation of this article.

Peter Rimmele is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s office in India.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.