Issue: 4/2024

Myanmar in the Fourth Year Following the Military Coup

On 1 February 2021, the military (Tatmadaw) staged a coup in Myanmar against the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi (ASSK), whose party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), had won a landslide victory in the November 2020 election. On the day of the constituent session of the newly elected parliament, State Councillor ASSK, State President Win Myint and other high-ranking parliamentarians were arrested. This led to a state of emergency being declared, and the internet was shut down. Shortly afterwards, the military formed the State Administration Council (SAC) to restore “peace and order”.

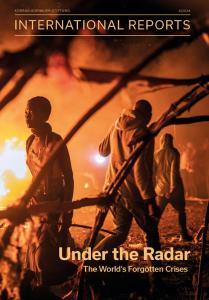

The takeover by the army initially led to widespread peaceful protests (“Civil Disobedience Movement”) on the streets of Myanmar, which the security forces gradually suppressed with increasing brutality. Mass killings, arbitrary arrests, torture, sexual violence and other abuses have been committed by the junta, all of which constitute crimes against humanity. The death penalty was also administered to four men after more than 30 years following summary and mock trials. The Head of the UN Human Rights Council, Nicholas Koumjian, stated in August 2024 that the “Myanmar military was committing war crimes and crimes against humanity ‘at an alarming rate’”.

Photos and reports of villages being burnt down are commonplace. Air strikes and attacks on the civilian population also take place time and again, notably in Kachin State in October 2022 when more than 100 civilians were killed (Hpakant Massacre) during a ceremony. Aerial bombardment has been dramatically increased throughout the last year, Mr Koumjian added. The United Nations’ Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM) reported that more than three million people are estimated to have been forced to flee their homes over the past six months alone. UN Human Rights Commissioner Volker Türk described the situation in Myanmar as a “never-ending nightmare”. Furthermore, the independent Assistance Association for Political Prisoners puts the number of fatalities caused by the military (as of 23 October 2024) at 5,871, as well as another 27,569 people arrested, while other estimates are much higher.

To add insult to injury, people are also suffering from the military conscription law (men: 18 to 35 years; women 18 to 27) enforced in early February 2024 by the SAC. This law also led to the migration of skilled workers and talented youth across Myanmar to neighbouring countries. The economy will continue to deteriorate in the foreseeable future, a recent World Bank report concluded. Much of the progress made during a phase of opening the country, especially under the civilian leadership of the NLD from 2015, has largely been reduced to nothing with half of the population living under the poverty line.

Decades under Military Rule

It is certainly not the first time that the people of Myanmar and in particular the various ethnic minorities in the border regions have suffered immensely at the hands of the Tatmadaw. Following a military coup in 1962, General Ne Win seized power in Myanmar and completely sealed off the country for more than half a century. All subsequent military dictators ruled the country with an iron grip. Peaceful protests for more democratisation and transparency, for instance, such as those in 1988 and 2007, were bloodily suppressed. Furthermore, massive election defeats for the political forces backing the military regime, such as in the NLD’s victory in 1990, were not recognised, and opposition figures such as ASSK were placed under house arrest even at that time.

In 2005, the military government moved the capital from Yangon to Nay Pyi Taw and amended the constitution three years later. That gave the military control over three ministries: defence, border and home affairs. They also have a fixed share of 25 per cent of parliamentary seats in the upper and lower houses, which amounts to a blocking minority for constitutional amendments. Myanmar’s 2008 constitution severely restricts the political participation of its many ethnic minorities, alienating them from common institutions such as parliament and ministries.

The Bamar people, Myanmar’s main ethnic group, make up about 69 per cent of the population and live mainly in the country’s heartland. While the various ethnic minorities, such as the Chin, Mon, Shan, Kachin and Karen, can mainly be found in the border areas with Bangladesh, India, China and Thailand. We hereby refer to the “ethnic states” that are dominated by an ethnicity which, speaking of Myanmar as a whole, constitutes a minority.

The appointment of Thein Sein (himself with a long military past) as the nominally civilian president in 2011 heralded the start of the country’s gradual opening. This resulted in free and fair elections in 2015 and an election victory for the NLD. Under the NLD-led government of State Councillor ASSK, priority was accorded to national reconciliation in the Panglong Peace Conferences. The aim was to bring ethnic armed organisations and the Tatmadaw to the negotiating table, get them to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), and to discuss the prospect of a more federal and equitable Myanmar – goals that are now emerging once again.

Ethnic organisations had resisted the military virtually since the country’s independence to defend themselves and their identity against successive dictators in Myanmar who pursued a policy of “Burmanisation”; this refers to a forced assimilation, ranging from the suppression of their teaching of ethnic history, language and culture, to military attacks, human rights violations and atrocities on civilians. The Tatmadaw ignored the pursuit of self-determination and even secession movements of the ethnic states and attempted to push the ethnic states into the “Union” through coercion and military might. The military still considers itself to be the “guardian of unity”, mandated to preserve the country from falling apart.

Broad Coalition against the Military

Shortly after the 2021 coup, Myanmar’s interim National Unity Government (NUG) was formed by the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), with authority derived from the people’s mandate in the 2020 election. The NUG comprises lawmakers from the NLD and other MPs who were ousted in the coup and are now forming the government in exile. In the political sphere, it has been working closely with the ethnic organisations, such as the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), Karen National Union (KNU), Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) and Chin National Front (CNF), also known as K3C, as well as other ethnic revolutionary organisations and ethnic political leaders. Their cooperation now increasingly extends to the battlefields, where the People’s Defence Force (PDF) acts as the NUG’s military arm.

It is crucial to note that the resistance encompasses broad sectors of society, both Bamar and the ethnic minorities. “The widespread anti-junta movement has moved on from calls to reinstate the 2020 election results […] to become a radical and intersectional Spring Revolution, aiming to fundamentally change state-society relations in Myanmar.” Almost all of the resistance groups have a joint understanding that the military poses a threat to the people of Myanmar and is what stands between them and a better future for the country and its people. The Myanmar military is deeply unpopular and overwhelmingly seen as the enemy of the state, except only for cronies, as well as families and businesses linked to the military.

State of the Military in 2024 – the “Enemy of the State”

Armed resistance from the ranks of the ethnic armed organisations and the PDF has recently become more professional. Pressure on the military has been growing especially since the powerful Three Brotherhood Alliance (consisting of three ethnic armed organisations) launched a comprehensive and highly successful offensive (Operation 1027) in northern Shan State in October 2023. The city of Laukkaing, on the border with China and known for gambling, prostitution and online fraud, which had previously provided the military junta with crucial hard currency, was captured.

In April 2024, for the first time in history, drones attacked the military stronghold and capital of Myanmar, Nay Pyi Taw. What is more, in August 2024, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), part of the Three Brotherhood Alliance, seized the northern town of Lashio in Shan State. Lashio hosts a regional command centre for the Myanmar military and is located along a vital trade route to China. While writing this paper, 53 towns were captured and controlled by the revolutionary forces in the Chin, Karreni, Nothern Shan, Rakhine, Kachin and Karen States. These successes against the military are unprecedented in the history of Myanmar. Loss of control over the outer areas of the country is also tantamount to the military no longer having access to important trade and communication links with India, China and Thailand, or only to a limited extent. Drug cultivation and the illegal trade in timber, jade stones and weapons are flourishing in these areas, especially in the northeast.

Although the junta continues to exercise control over the populous and economically important heartland of Myanmar, including major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, it faces entirely new challenges. Reports indicate defections from the military ranks or surrenders. In August 2024, there were rumours that the army chief had been toppled by fellow generals, highlighting the poor morale of the military, which is reported to be at an all-time low. This decline has led to young people being forcibly conscripted into its armed forces. The military’s capacities for personnel are exhausted and overstretched, making it unable to rotate or re-deploy troops or regain lost ground after three and a half years of fighting on various fronts.

The junta is desperately trying to gain international recognition to officially and unequivocally represent the country to the outside world. Besides North Korea, Russia and China, it remains almost completely isolated in the international arena. The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine also ties up Russian war material, which, in turn, means that less military equipment can be delivered to Myanmar. Still, as a Washington Post article notes, rebel advances have been increasingly halted recently due to the military’s deployment of superior drones received from Russia. Faced with a lack of alternatives, a shortage of hard currency and tight international sanctions, Myanmar’s generals are now turning to North Korea for the purchase of weapons. Despite these developments, predictions of the junta’s imminent collapse are premature and misleading, as the Tatmadaw still has many soldiers within its ranks and military-technical superiority, not to mention a climate of fear cascading down the hierarchy.

Regional-led Solutions for Myanmar?

A few months after the coup, in April 2021, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Myanmar junta agreed on a so-called “Five-Point Consensus”. Myanmar is one of the ten Member States of ASEAN, and therefore, the EU, US and neighbouring countries have expressed an expectation that conflict resolution must be ASEAN-centred and ASEAN-led.

The “consensus” included an immediate end to violence in the country, dialogue among all parties, the appointment of a special envoy, humanitarian aid from ASEAN and a visit by the special envoy to Myanmar to meet with all parties. However, after only two days, the Tatmadaw said that “ASEAN’s proposals would be considered when the situation stabilises” and that “the restoration of law and order” would be given priority. Similarly, in October 2021, the junta refused to allow the ASEAN special envoy to Myanmar to visit ASSK and other detained members of the democratically legitimised government – a precondition for his visit, which was subsequently cancelled.

At the highly anticipated ASEAN Summit in September 2023 under Indonesia’s presidency, agreement was reached on a paragraph in the final declaration. Still, ASEAN has not been able to make much progress in dealing with Myanmar since the coup.

With Laos as chair, expectations of a regional-led solution were low in 2024, as the country was mainly imitating Cambodia to engage with the generals following a quiet diplomacy approach. For the first time since ASEAN barred Myanmar from sending political representatives in 2021, Laos, as chair, invited a high-level representative from Myanmar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is linked to the military.

ASEAN leaders remain divided on how to deal with the crisis in Myanmar, largely because of the diverse political systems within the association – ranging from democracies like Indonesia to autocracies like Cambodia and conservative monarchies like Brunei – or historical ties with the generals in Nay Pyi Taw. For example, former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen paid a visit to the military regime in 2021, and Thailand’s former Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha (who also rose to power through a coup in 2014) maintained contacts with the military government; actions that were heavily criticised by Indonesia and Malaysia which advocated a stricter and more decisive stance against the junta. Fast forward, with Paetongtarn Shinawatra in Thailand, who assumed premiership of the country in August 2024 and the transition of leadership in Singapore with Prime Minister Lawrence Wong taking over in May, some new impulses were secretly hoped for. However, it never went beyond wishful thinking.

While the issue of Myanmar notably receives centre stage in ASEAN Summits or Foreign Ministers’ Meetings in an attempt to showcase and promote “unity”, a breakthrough within ASEAN seems highly unrealistic. The joint communiqué during Indonesia’s chairmanship in 2023 already hinted at ASEAN’s inability to solve this “internal crisis” in Myanmar, acknowledging that it was time to invite external actors. This now becomes more realistic with Thailand’s push for an informal ASEAN ministerial-level consultation on Myanmar in mid-December, potentially opening the forum to neighbouring actors such as China and India. China has a strong influence on Myanmar’s domestic politics thanks to longstanding relationships with ethnic organisations along its border and the generals in the capital.

In 2025, Malaysia will hold the fifth chairmanship to oversee the crisis in Myanmar since the coup in 2021. Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, who has been very focal on foreign policy to date, is expected to reiterate the Myanmar issue. Still, without the consent (unanimity) of the ten members, a single member state cannot accomplish much.

The Way Ahead

Prompted by the above-cited military victories in the ethnic states and the absence of talks between the fighting parties, most ethnic revolutionary organisations are attempting to become de facto states in their controlled areas and have already begun to organise interim arrangements. As noted, some ethnic states in the north, northeast and east of the country have fiercely resisted military rule since independence and fought for self-determination and greater autonomy. The objective of becoming a de-facto state now seems more feasible than ever.

Ethnic states have been providing basic government services such as security, education and health in their area of control. In Shan State and the Kokang Self-Administered Zone for example, “parallel structures” have emerged over the years. The Karen National Union’s territory has vastly expanded since the military coup. If the many ethnic armed organisations continue to join the armed resistance alongside the PDF and continue to set aside their at times disputing and conflicting claims, they could greatly contribute towards ending military rule in Myanmar. While some ethnicities and groups in Myanmar are now actually seeking greater autonomy, democratisation and federalism, including a possible secession from Myanmar in a separate state, other groups primarily want to expand their territories and sphere of influence.

It is important to acknowledge that debates are already being held about a “post-war state” or “post-junta Myanmar”, referring to a time when the military is defeated or no longer in an influential position. Actors are calling for greater control over the country’s resources, fairer representation in parliament and a true federal system that confers more decision-making power on ethnic states. These and similar demands were already raised during Myanmar’s post independence negotiations – in the formation and discussion of the Union of Burma (the country’s former name) based on the Panglong Agreement – revisited in the Panglong Peace Conferences under Aung San Suu Kyi and her NLD from 2016 onwards and are now being addressed once again.

Unsurprisingly, the military has different plans: the junta will be trying to conduct a census in 2025 ahead of the planned elections in November to gain legitimacy. The military currently controls less than half of the country and the majority of Myanmar decided to plan for a military-free future and a complete restructuring of the polity. An election conducted under the military regime would be anything but free and fair. The international community should be on guard though, as some countries (also in ASEAN) may seek this as a welcoming option to normalise their ties with Myanmar.

At the same time, the military is systematically eradicating the NLD’s top officials, one by one, by withholding vital medical treatment from the detained NLD members. Four of its ageing leaders have died, while three others have been imprisoned. U Nyan Win, a senior adviser to deposed leader ASSK, died from a COVID-19 infection in Yangon’s Insein Prison. Monya Aung Shin, a senior leader and spokesperson died from a heart attack one month after he was released from an interrogation centre in Yangon. Zaw Myint Maung, NLD vice-chairman and former chief minister of Mandalay Region, succumbed to leukemia, having been denied adequate medical treatment. The 79-year-old State Councillor ASSK, 71-year-old President Win Myint and 83-year-old NLD patron Win Htein are still imprisoned, raising concerns over their health among the people. At Zaw Myint Maung’s funeral, some 10,000 people gathered to pay their respects, despite military pressure.

Germany, along with its European and international partners, accompanied and supported the country in its gradual political transformation and opening via the provision of development assistance and notably also facilitated the Panglong Peace Conferences based on the NCA. Ideally, this should have contributed to a national reconciliation.

It is impressive to see how the brief period of openness under the NLD has helped the population to embrace democratic and liberal principles. This development became noticeable after the 2021 coup and led to reactions ranging from an initial civil disobedience movement and widespread peaceful protests on the streets to the creation of the PDF and the formation of alliances between armed ethnic organisations.

A solution to the conflict must be driven primarily by neighbouring countries, while the international community has a responsibility to raise awareness about this increasingly overlooked conflict, too. As the coup recedes into the past, Myanmar risks becoming a “silent conflict” far away from the attention given to Gaza and Ukraine. Yet, it is still characterised by immense suffering for all its people – Bamar and ethnic minorities alike – the future of whom is denied by the junta’s sheer intransigence.

Moritz Fink works as a Policy Officer for the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Regional Programme Political Dialogue Asia, Singapore. He lived and worked in Myanmar in 2017.

Saw Kyaw Zin Khay is a visiting Research Fellow at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Department Asia and the Pacific.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.