Overview – Skip to a certain paragraph:

☛ National Chairman of the CDU and Opposition Leader

☛ Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

☛ Foreign-policy Successes and German Reunification

☛ Connection between German and European Politics

☛ Post-Chancellor Years, 1998–2017

Helmut Kohl was born on 3 April 1930 in Ludwigshafen am Rhein. His political career got off to an early start in 1946 when he co-founded the Junge Union of Rhineland-Palatinate, a youth organization of the conservative political parties CDU and CSU. After completing secondary education in 1950, he studied history, law and political science, first in Frankfurt am Main and then in Heidelberg. It was in Heidelberg, in 1958, that he obtained his doctorate in the field of modern history with the dissertation Die politische Entwicklung in der Pfalz und das Wiederentstehen der Parteien nach 1945 .

Kohl was keenly interested in the history of his native south-western Germany – not just contemporary events, but all the way back to the Middle Ages. The Gothic cathedral in Speyer, for instance, always remained for him one of the greatest religious and historical monuments and symbols of Occidental Christian culture.

Although his political career began in his teens, Kohl worked in industry full-time for many years after completing his studies. He began as an assistant manager in an iron foundry, from 1958 to 1959, and from then until 1969 he worked at the Rhineland-Palatinate branch of the German chemical industry association (VCI). Kohl held his first political offices while still a student in Heidelberg, and many others followed in later years. In 1959, he won a seat in the Landtag (state parliament) of Rhineland-Palatinate, which he kept until he was elected to the Bundestag in 1976. From 1963 to 1969, he served as the chairman of the CDU parliamentary group in the Landtag, and from 1966 on, he was the CDU state chairman and a member of the CDU’s national executive. In 1969, when he was only 39 years old, Kohl became the minister president of his home state, Rhineland-Palatinate – an office that he held until 1976.

Kohl’s impressive political career at the state level was characterized by active involvement at all levels of the CDU, including local politics, and he developed a wide range of acquaintances as a result. His youthful zeal for reform was apparent, as was his appetite for power – the latter was evident in the way Kohl and the younger generation of politicians forced aside and replaced Peter Altmeier, his predecessor as party chairman and minister president. Kohl pursued his political advancement with focus and determination, and he clearly found capable associates to accompany his rise, both then and later. During his time as minister president in Mainz (the capital of Rhineland-Palatinate), these included his minister of education and cultural affairs, Bernhard Vogel, who later succeeded him there.

In 1960, during his years in Ludwigshafen, Kohl married Hannelore Renner, who had studied linguistics in Mainz. The couple had two sons: Walter was born in 1963 and Peter in 1965. Kohl often stressed how important family life was to him.

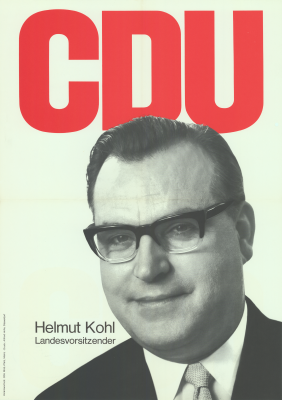

National Chairman of the CDU and Opposition Leader

In 1973, Helmut Kohl stood a second time for the position of CDU national chairman, after Rainer Barzel, the incumbent, had decided not to run again. His election took place during a difficult phase for the party. Although the CDU/CSU remained the largest parliamentary group after the Bundestag election of 1969, it was pushed into opposition when the SPD and FDP agreed to form a new coalition government. The party entered a period of crisis, which was aggravated by controversies surrounding the new government’s policy towards Eastern Europe and the division of Germany. It was further exacerbated by the defeat at the polls to Willy Brandt in 1972. In response, Kohl worked to increase the power of the party leadership relative to that of the CDU group in the Bundestag, where he was unable to act as opposition leader. At the same time, he energetically pursued reforms in the organizational structure and programme of the CDU, which had been described derisively since the days of Konrad Adenauer (not entirely without reason) as a “club for electing the chancellor”. To that end, he brought in energetic, hands-on general secretaries and gave them the task of introducing structural reforms. The first to take on this role was the economics professor and sometime industry executive Kurt Biedenkopf (1973–1977). He was followed by social policy expert Heiner Geißler (1977–1989). The result was an effective reorganization of the party headquarters and the party machine. The party’s internal consultation process was improved and there was a huge increase in membership, which rose from 457,393 to 718,889 between 1973 and 1982. With regard to the substance of its programme, the high point came with the 1978 CDU party conference in Ludwigshafen and the manifesto adopted there.

There is no doubt that, for Kohl, the CDU was always more than just a party-political organisation; it was something that lay close to his heart. That may explain his extensive knowledge of party life and party officials, which was legendary. In any event, he is considered one of the greatest party chairmen in the history of the Federal Republic.

The CSU’s chairman, Franz Josef Strauß, was the most effective and eloquent opposition leader to emerge since the union of CDU and CSU lost power in 1969. This led to friction between the two party chairmen early on.

As the frontrunner and chancellor candidate for the CDU/CSU union, Kohl achieved a fantastic result of 48.6% in the Bundestag election of 1976, which had an extremely high turnout of 90.7%. This was the second best result in the two parties’ entire history, after the so-called ‘Adenauer election’ of 1957. The CDU/CSU thus became the strongest group in the Bundestag once more, six percentage points ahead of the major party in the governing coalition, the SPD, despite the incumbency advantage of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt.

Paradoxically, it was precisely this electoral success that led to the disagreement between the CDU and CSU chairmen regarding strategy: while Kohl hoped that the FDP would opt for a new coalition with the CDU and CSU in the medium term and, to that end, fostered good relations with FDP chairman Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Strauß considered it unrealistic to think the FDP would take that step, at least for the foreseeable future. Nasty verbal attacks on the CDU chairman escalated the argument, as did the decision by the CSU regional group in the Bundestag to discontinue the parliamentary alliance with the CDU, which had existed since 1949 – and had originally been formed at the initiative of Strauß. The maxim of this decision, which was taken at a party gathering in Kreuth, Bavaria, was to ‘March divided, strike united!’ Kohl responded promptly with a threat to establish a Bavarian branch of the CDU, heightening the fierce debate underway within the CSU. Soon afterwards, however, the two party chairmen pragmatically agreed to continue working as a single parliamentary group in the Bundestag.

Kohl’s reaction to the election of 1976 was far-sighted. Although he was not elected chancellor, he gave up the office of Minister President of Rhineland-Palatinate. As the chairman of the CDU/CSU group in the Bundestag, he became opposition leader, facing a much weaker SPD/FDP government under Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Nevertheless, he had trouble competing with Schmidt on the public stage, as the latter was very experienced in national politics and a man of rhetorical brilliance. This and some clumsy moves on Kohl’s part led to mounting criticism of him within the party, and he opted not to seek the nomination as chancellor candidate for 1980. This, too, was a far-sighted decision. Without consulting the CSU, Kohl then brought forward Ernst Albrecht, the minister president of Lower Saxony, for consideration as a chancellor candidate. The reaction of the CSU could not have been harsher; it forced a vote within the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, in which Franz Josef Strauß won against Albrecht. This victory for Strauß, who privately had doubts about accepting the candidacy, proved to be short-lived.

Kohl supported him in the ensuing election campaign. Despite sustained and sometimes defamatory attacks from print media such as Der Spiegel and Die Zeit, Strauß did succeed in making the union of CDU and CSU the strongest group in the Bundestag in 1980. It won 44.5% of the vote, ahead of Chancellor Schmidt’s governing party at 42.9%. But the FDP stayed in the coalition with the SPD – as Strauß had foreseen.

Kohl had again proven that he could wait for the right moment, and he refused to be discouraged by setbacks. The election result of 1980 finally resolved the power struggle playing out at national level between the CDU and CSU chairmen, in favour of Kohl. And although the coalition government remained in place, both men recognized that the unity between the SPD and the FDP was being gradually eroded by conflicting objectives in economic and social policy, and later in foreign and national security policy.

In the autumn of 1982, the government collapsed. Helmut Schmidt no longer had enough backing in his own party (SPD), and the FDP was no longer willing to lend its support to the misguided economic and financial policies that the left wing of the SDP was increasingly trying to force upon its own chancellor. Marshalling a majority within the party, SPD Chairman Willy Brandt torpedoed Schmidt’s security policy and the NATO Double Track Decision of 1979.

Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

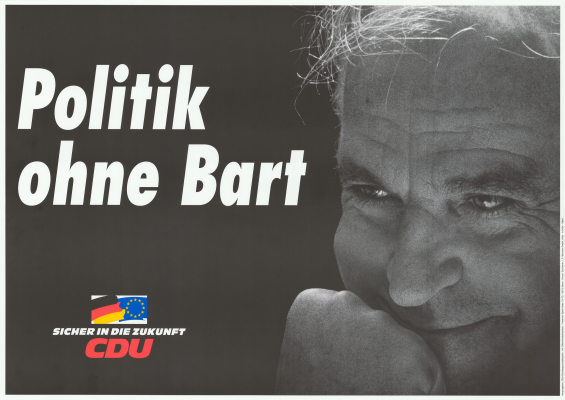

The election of Helmut Kohl as chancellor through a constructive vote of no confidence on 1 October 1982 marked the beginning of the next and doubtless most significant phase of his political career, in which he remained chancellor for sixteen years – longer than anyone before him. Although opinion polls often predicted defeat, he won every parliamentary election until 1998, in line with his dictum: “They win the opinion polls; we win the elections.”

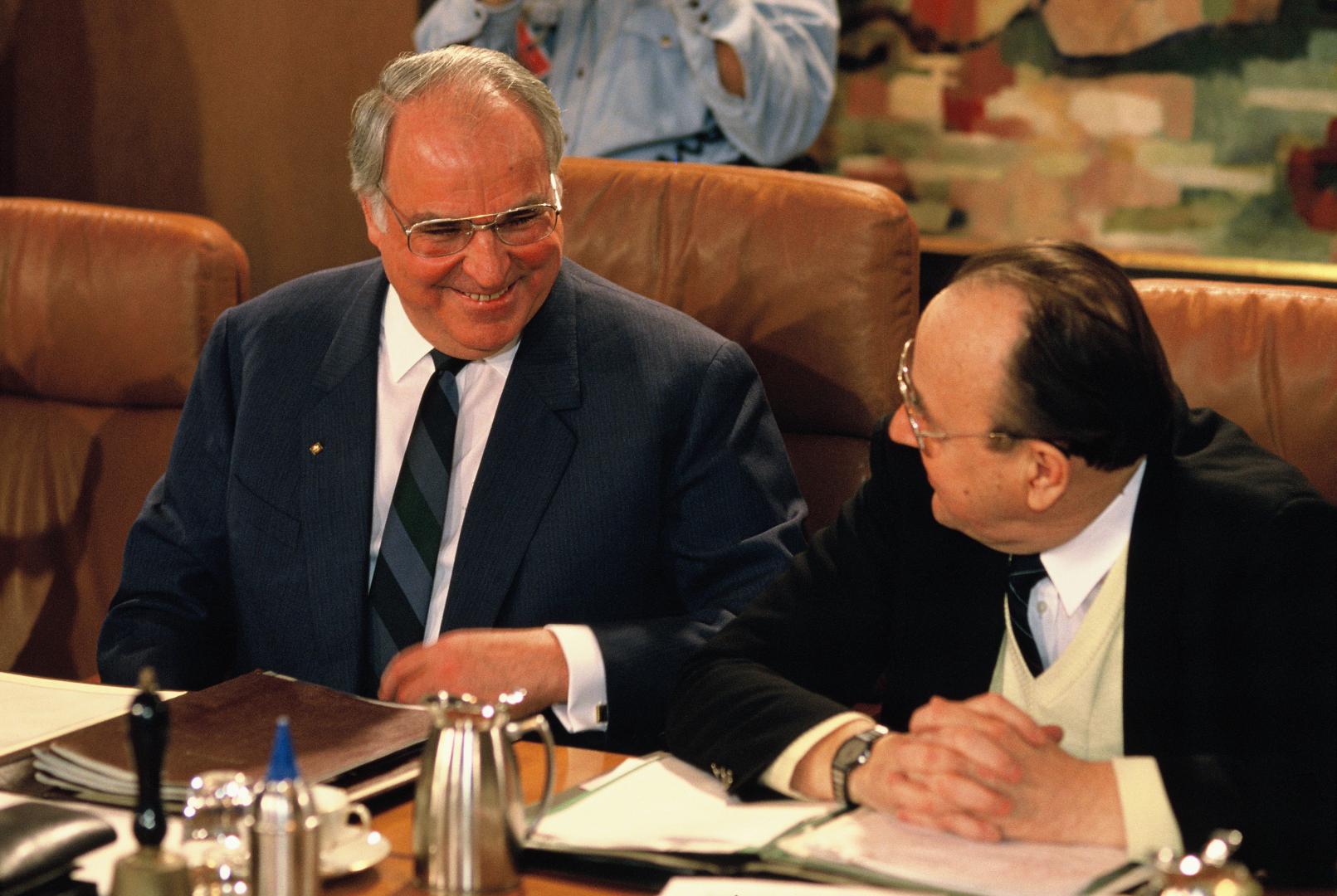

The chancellorship got off to a bumpy start in 1982–83, particularly in light of the fact that Kohl and Franz Josef Strauß disagreed about the date for an early general election. Strauß hoped that the FDP’s switch from one coalition to another would lose it enough support among voters to keep it out of the Bundestag entirely. This risk led the FDP to reject an early date, and Kohl kept his promise to Hans-Dietrich Genscher not to hold elections before March 1983. The biggest problem, as it turned out, was that the new coalition initially lacked a satisfactory candidate to serve as head of the chancellery. Ultimately, Kohl appointed Wolfgang Schäuble to this position in 1984, and henceforth it operated efficiently and without any slip-ups.

In addition to Schäuble, Kohl brought other highly-qualified advisers to his side. Some of them had worked with him in Mainz or at the party headquarters (the Konrad-Adenauer-Haus in Bonn), notably Horst Teltschik in the field of foreign policy. Kohl’s cabinet also contained heavyweights from each coalition partner. From the CSU, for instance, there was Friedrich Zimmermann as minister of the interior. From the FDP came Hans-Dietrich Genscher as foreign minister and Otto Graf Lambsdorff as minister of economic affairs. The CDU contributed Norbert Blüm as minister of labour and, in the key position of minister of finance, Gerhard Stoltenberg, the long-serving minister president of Schleswig-Holstein.

Although Kohl set great store by loyalty, he wasn’t afraid to have independent minds in his government. Stoltenberg was of particular importance, given that one of the basic demands of the CDU/CSU, when in opposition, had been to put budgetary policy on a firmer footing. Moreover, Stoltenberg worked in partnership with Otto Graf Lambsdorff, whose differences with the SDP over economic policy had played a major role in the FDP’s decision to align with a new coalition partner.

The Kohl Era Until 1989

The aforementioned fiscal reorganization took on great importance in the longer term, when Germany began to face the huge costs of reunification after 1990 onwards. In intra-German policy and foreign affairs, the new chancellor held to a course of continuity in many respects, belying the expectations of those who predicted regressive steps. In contrast to his predecessor, Helmut Schmidt, and despite the strong political headwinds of adverse public opinion and numerous mass demonstrations, Helmut Kohl even succeeded in implementing the NATO Double-Track Decision, which was the outcome of a debate initiated by Schmidt himself. This decision ultimately contributed to the economic decline of the Soviet Union by forcing it to maintain very high levels of military spending.

Kohl’s demand for a spiritual and moral turnabout, supposedly endorsed by voters in his election to the office of Federal Chancellor, has often been politely ridiculed, yet the legacy left by Kohl in the field of cultural and educational policy is greater than any chancellor before him or since. Notable achievements in this regard include his initiatives in the field of history and politics, such as his support for the House of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn, and the German Historical Museum in Berlin. He also provided the impetus for the formation of German historical institutes abroad and for cultural facilities in Berlin. These buildings were largely erected under the aegis of his construction minister and later personal representative, Oscar Schneider (CSU); the projects were run from the chancellery by Minister of State Anton Pfeifer, who was responsible for science and research.

Kohl was nevertheless underestimated, not just by left-wing liberal intellectuals and media, but also by political opponents and rivals in his own party. Not only was he well versed in the tactics of party politics and the acquisition and exercise of power; he was also an exceptionally well-read and far-sighted strategist, thanks in part to his profound knowledge of history. In that respect, he certainly did resemble his CSU counterpart, Franz Josef Strauß. Another point of similarity is that neither man tried in the least to repress the history of Nazi Germany. This far-fetched charge was laid at Kohl’s doorstep on several occasions. In one notable case, a storm of indignation roiled the media when Kohl and President Ronald Reagan visited the German military cemetery in Bitburg. Although some members of the SS were buried there, it was primarily a cemetery for soldiers of the Wehrmacht, the wartime German army.

By contrast, Kohl’s major speech in April 1985 commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was practically ignored, although like many other addresses that Kohl delivered, it contained an unequivocal assessment and condemnation of the crimes committed by Nazi Germany. As a historian, Kohl’s interest was actually to confront the entirety of German history and to draw lessons from it, in a spirit of reflection, for political decision-making.

This is one of the reasons why Kohl was better prepared for the years 1989–90 than many of his opponents: thinking and acting with a long-term historical perspective, he had never given up on German reunification, an objective postulated in the Basic Law of the Federal Republic itself. When this prospect opened up unexpectedly in the autumn of 1989, he recognized and seized every opportunity with that purpose in mind, demonstrating superb diplomatic skill and exceptional staying power.

Foreign-policy Successes and German Reunification

Helmut Kohl and his foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, can be credited with a number of foreign-policy achievements of long-term importance, among them a strengthening of relations with neighbouring countries. France was a particular focus, and Kohl developed a close personal relationship with President François Mitterrand. He also brought about a lasting improvement in relations with the United States and its presidents: Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Within the European Union, Kohl knew how to take into account the interests of the smaller member states, which earned him considerable trust. His policy with regard to European integration led to constructive collaboration with the President of the EU Commission, Jacques Delors. Kohl also applied himself to the furtherance of German-Polish rapprochement. And after an initial period of disgruntlement on the part of Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR, following an unfortunate interview given by Kohl, in which he seemed to compare the public relations abilities of Gorbachev with those of Goebbels, he developed an ever better relationship with the Soviet leader too.

The esteem in which Kohl was held internationally and the trust he enjoyed among many statesmen proved to be a priceless asset during the process of reunification in 1989–90. Of course, there were many causes, both short-term and long-term, for the erosion of the Communist dictatorships and, therefore, of the Warsaw Pact. The West German chancellor could take credit neither for the civil rights campaigns in the East, nor for the growing wave of emigration and flight from the GDR, which ultimately led to the Peaceful Revolution. These developments, however, by no means automatically brought about reunification. That process was much more complex and could not be achieved through intra-German rapprochement alone. It rather depended, crucially, on international negotiations. Even among the governments of friendly nations, the dominant stance was of opposition to reunification, in part for historical reasons. Many of them viewed the re-emergence of a disproportionately powerful German state in the middle of Europe as a threat. In particular, they worried that German economic strength and political power would become even greater.

With the trust he had built up, and with sensitive diplomacy, Kohl was able to overcome this resistance of the part of Germany’s European neighbours. The support of the United States, in the person of President Bush, proved to be indispensable in this regard. In arduous negotiations with Gorbachev, Kohl ultimately obtained his consent to NATO membership for a united Germany. This was one of the conditions that Kohl and Bush insisted on, but it was a very difficult one for the Soviet leadership to accept. Mitterrand was hesitant, but he was won over by the argument that reunification would play into the process of European integration that was being promoted by both himself and Kohl: the ties of an even more integrated Europe, it was proposed, would also bind a reunited Germany.

Achieving this objective, so energetically pursued by Kohl since the opening of the inner-German border and the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, required not just rapid decision-making and constant negotiation with many different governments, but also some tactical manoeuvring. The Ten-Point Plan of 28 November, for example, proved to be a skilful, attention-grabbing move. Although the plan wasn’t realized, it sent an unmistakable signal: we want reunification, and we are proposing concrete steps towards that objective. The ongoing peaceful revolution soon rendered the plan obsolete, but its progress also gave Kohl leverage internationally. Before this leverage diminished, he made sure to lay the groundwork for the definitive recognition of the post-war German-Polish border (the Oder-Neiße line), both domestically and at the international level.

A great many activities and initiatives had to be coordinated. These included the ‘2 plus 4’ talks by the Allied Powers and the two German foreign ministers (Genscher played a major role on behalf of West Germany, while Markus Meckel, SPD, and then Minister President Lothar de Maizière, CDU, represented East Germany); the arduous intra-German negotiations on the unification treaty, held by Wolfgang Schäuble with State Secretary Günther Krause of the GDR; and the measures that Finance Minister Theo Waigel introduced to support economic and monetary union. The fact that experts considered the economic and monetary union to be premature and overly ambitious did not diminish the need to decide the issue for political reasons. Nor should we lose sight of the fact that Kohl, in collaboration with Schäuble, lobbied heavily for the Bundestag to move the seat of government from Bonn back to Berlin as the capital. He also promoted huge investments in the eastern Länder with a view to turning them into “blühende Landschaften” (flourishing landscapes) – a goal which, despite many problems inherited from the years of GDR dictatorship, was largely realized within a single generation.

Although the window of opportunity was open only briefly, Kohl ultimately managed to constructively and efficiently combine the developments underway in the two parts of Germany with his foreign policy towards both western and eastern neighbours. There is no doubt that he deserves the lion’s share of the credit for German reunification, and thus for one of the most significant events in twentieth-century German history. For the first time since the ‘German problem’ had emerged in the seventeenth century, a solution was achieved by purely political, diplomatic and economic means – peacefully, in other words – in contrast to Bismarck’s founding of the German Empire in 1870–71.

Connection between German and European Politics

This outstanding feat of statesmanship was dialectically linked with fundamental decisions concerning European integration, namely the Maastricht Treaty, the Schengen Agreement and the introduction of the euro. The feats that Helmut Kohl accomplished as a major player on the European stage, for which he was rightly granted the title of “Honorary Citizen of Europe,” are often accorded greater recognition abroad than in his own country. Violations of the stability criteria of the Maastricht Treaty have been criticized, as have eurozone bailout policies, and such criticism is doubtless justified; however, the responsibility for them lies not with Helmut Kohl and Theo Waigel, but with those who later ignored core treaty commitments.

The third major achievement of Kohl’s foreign policy was his blueprint for lasting peace in Europe, which was to include not just the nations of Central and Eastern Europe, but also Russia. Although this visionary project initially seemed on track after the end of the Cold War in 1989–91, it remains on ice for the time being. But in this field as well, Kohl is responsible neither for subsequent mistakes, nor for the disputes between Russia and the West. He also helped to promote the perhaps too rapid eastward expansion of the EU. And by ensuring the withdrawal of the Red Army (450,000 troops and personnel) from the territory of the former GDR, he removed a major encumbrance for not only a reunified Germany, but also for Poland and the Baltic states, which no longer had to fear intervention from both directions. Yet Kohl was always convinced that post-Soviet Russia would have to be an essential part of the new order that was being built to secure peace, and it was with this objective in mind that he approached his relationship with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia.

In sum, even though the development of the EU has been problematic in some respects, and although the blueprint for a lasting European peace – introduced with so much promise in the 1990s – has so far been implemented only in part, the basic principles of these policies remain indispensable.

Post-Chancellor Years, 1998–2017

In his later years, Helmut Kohl endured a number of bitterly painful experiences, chief among them the death of his first wife Hannelore in the year 2001, which affected him deeply. Later, he suffered a fall that had severe long-term consequences for his health. The ever-present and imposing ‘giant of Oggersheim’ in a wheelchair? Inconceivable. After that, he was hardly able to mount any defence, by himself, against disparagements of his life’s work.

In the public sphere, there was the CDU donations scandal that emerged in 1999–2000. Kohl had failed to declare several large donations during his term as CDU chairman – thus violating the Political Parties Act – and later he refused to name the donors. He derived no personal financial gain from these actions and during the years in question, these donations had made up only a fraction of the annual CDU budget. Furthermore, he compensated the party from his own funds for the fines that were imposed. But the damage to his reputation proved to be irreparable and long-standing allies within the party fell out with him permanently. As a consequence of the scandal, he had to resign from his position as honorary chairman of the party. The last years of his life were spent mostly at his home in Oggersheim, with the indispensible support of his second wife, Dr. Maike Kohl-Richter, whom he had married in 2008. He still managed to release some relatively brief statements and other writings, but he was unable to complete the fourth volume of his memoirs.

Present-day Europe has been shaped to a great extent by German unification in 1989–90, by European integration and by the new, peaceful order established in the 1990s. Kohl played a prominent role in all of these developments, making him one of the greatest German statesmen of the twentieth century. After years of suffering due to poor health, Helmut Kohl died on 16 June 2017, at the age of 87, in his native city of Ludwigshafen. Leading politicians from around the world attended a ceremony in his honour at the European Parliament in Strasbourg, at which Chancellor Angela Merkel, President Emmanuel Macron, EU Commission President Jean-Claude Junker and others paid tribute to a great European. On 1 July 2017, he was buried in the Alter Friedhof cemetery near the Church of St. Bernhard in Speyer.

The original text was translated into English by Richard Toovey.

Curriculum vitae

- 1950 Completes secondary education (Abitur) in Ludwigshafen

- 1950–58 Student of history, law and political science in Frankfurt am Main and Heidelberg; doctoral degree from Heidelberg University in 1958 1959–69 Manager at the German chemical industry association (VCI)

- 1947 CDU member, co-founder of the Junge Union (JU) in Ludwigshafen

- From 53 Member of the committee of the Palatinate branch of the CDU

- 1954–61 Deputy chairman of the Rhineland-Palatinate JU

- 1955–66 Member of the committee of the Rhineland-Palatinate CDU

- 1959 Chairman of the CDU district chapter for Ludwigshafen

- 1960–69 City councillor and leader of CDU councillors in Ludwigshafen

- 1959–76 Member of the Landtag (state parliament) of Rhineland-Palatinate

- 1961–63 Deputy Chairman of the CDU parliamentary group in the Landtag

- 1963–69 Chairman of the CDU parliamentary group in the Landtag

- 1963–67 Chairman of the CDU regional chapter for the Palatinate

- 1966–74 Chairman of the CDU in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate

- 1969–76 Minister President of Rhineland-Palatinate

- 1969–73 National vice-chairman of the CDU

- 1973–98 National chairman of the CDU

- 1976–2002 Member of the Bundestag

- 1976–82 Chairman of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Bundestag

- 1982–98 Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany