Overview – Skip to a certain paragraph:

☛ Regaining Political Freedom of Action and Rebuilding the Country

☛ The Adenauer CDU as the ‘Party of the Federal Republic’

☛ Establishing a Social Market Economy

☛ The Invention of Chancellor Democracy

☛ Policy on Germany as a Whole

I. 1876–1949

Conrad (with a ‘c’) was the third of the five Adenauer children and he grew up in cramped conditions. After graduating from high school in 1894, he studied law and economics in Freiburg, Munich and Bonn on a municipal scholarship. After the first state examination in law, a legal traineeship, and the second state exam, he worked first as an examining magistrate in the public prosecutor’s office in Cologne and then, from 1903, for the lawyer Hermann Kausen (chairman of the Centre Party group on Cologne council) and from 1905 as an assistant judge at the regional court. In 1904, he married Emma Weyer (1880–1916) and thus became a member of high society in Cologne. The couple had three children together. Adenauer’s outlook was shaped by Christian and humanist values with a Catholic foundation; he never lost the liberal spirit of the Rhineland with its openness to western Europe and he remained influenced by the democratic and federalist tradition of the Centre Party in the Rhine region.

In 1906, Konrad Adenauer was elected an alderman of the City of Cologne, and in 1909 became First Alderman. His wife died in 1916 and he suffered serious injuries in a car accident in 1917. In the same year, he was elected Mayor of Cologne. Kaiser Wilhelm II changed the title to Lord Mayor and appointed him a member of the Prussian parliament (Herrenhaus). In 1919, Adenauer married Auguste Zinsser (1895–1948). They would have four children together. An interesting light on his character is cast by the fact that he spent a lot of his spare time exploring new applications of technology and even registered patents. For sixteen years, Adenauer shouldered responsibility for Cologne’s fortunes, transforming the cathedral city on the Rhine into a modern metropolitan centre for the west of Germany. Late in 1918, British troops marched into the city, beginning a seven-year period of occupation. As the ‘Rhineland movement’ gathered strength during the winter of 1918–19, he advocated the secession of the Rhineland from Prussia, but not from the German Empire. During the political and economic crisis in the autumn of 1923, he opposed the efforts of the national government, headed by Gustav Stresemann, to separate the west of Germany from the Empire for a period in order to save ‘the rest of Germany’. Adenauer took the French need for security seriously and sought to foster ‘organic interdependence’ between the heavy industries of western Germany and those of neighbouring countries.

As a Centre Party politician, he occupied leading positions in the Rhenish provincial assembly and its executive committee; from 1921 onward, he was also a member of the Prussian State Council. He was re-elected president of the council in every subsequent year until 1933. When he presided over the 1922 ‘Catholics’ Day’ festival in Munich, he promoted cooperation between different denominations of Christianity. Re-elected Lord Mayor in 1929, he drew the hatred of the National Socialists, for whom he embodied the bastion of republicanism in Prussia. After Hitler came to power, Adenauer was powerless – even as President of the State Council – to prevent Prussia being brought under Nazi control when the state’s parliament (Landtag) was dissolved on 6 February 1933. After the local elections on 12 March, Adenauer was removed from the office of Lord Mayor and on 17 July he was dismissed from the municipal service.

For a long time, he was threatened, banned and kept under surveillance. He took refuge in the Benedictine monastery of Maria Laach for a year in 1933–34. In 1934, he and his family moved to Neubabelsberg near Berlin, but he was placed under arrest for two days in June 1934. In 1935, he moved to Rhöndorf. After being banned from the Cologne metropolitan region, he lived in Unkel for a year. In 1937, he reached a settlement with the authorities in Cologne, which allowed him to build a house in Rhöndorf. Adenauer avoided contact with German opposition groups. On 26 August 1944, he was arrested and incarcerated in Cologne for three months. His wife was also kept under arrest for a while, which damaged her health and contributed to her subsequent death in 1948. Appointed Lord Mayor of Cologne by the American military authorities on 4 May 1945, Adenauer did everything possible to rebuild the devastated city. His relationship with the Americans was good, but at the end of June, they handed over to the British occupation administration and tension developed. On 6 October 1945, he was dismissed by the British military governor. He was also forbidden to engage in political activity, so he resigned from the executive committee of the newly founded Christian Democratic Party (a regional precursor of the CDU), to which he had been apponted on 2 September. Once the prohibition on his political activity was lifted, Adenauer resumed his political career in spectacular fashion, accumulating every leadership position in the CDU of North Rhine-Westphalia and the British zone. He also headed the CDU/CSU working group that was set up in 1947 and, as an organiser and effective public speaker, played a decisive part in the rise of his party.

Adenauer drew his own conclusions from the division of Germany and Europe: ‘no’ to the historical ‘see-saw policy’ and the restoration of the old nation-state, and ‘yes’ to the integration of West Germany in Western Europe. With his election as president of the Parliamentary Council on 1 September 1948, Adenauer assumed a key position in interstate supra-regional politics. As the ‘nascent Federal Republic’s spokesman towards the Western powers’ (T. Heuss), he was able to generate resonance for his concept of West Germany’s role in the free world and simultaneously reinforce his claim to the leadership of the Federal Republic of Germany.

II. 1949–1967

Regaining Political Freedom of Action and Rebuilding the Country

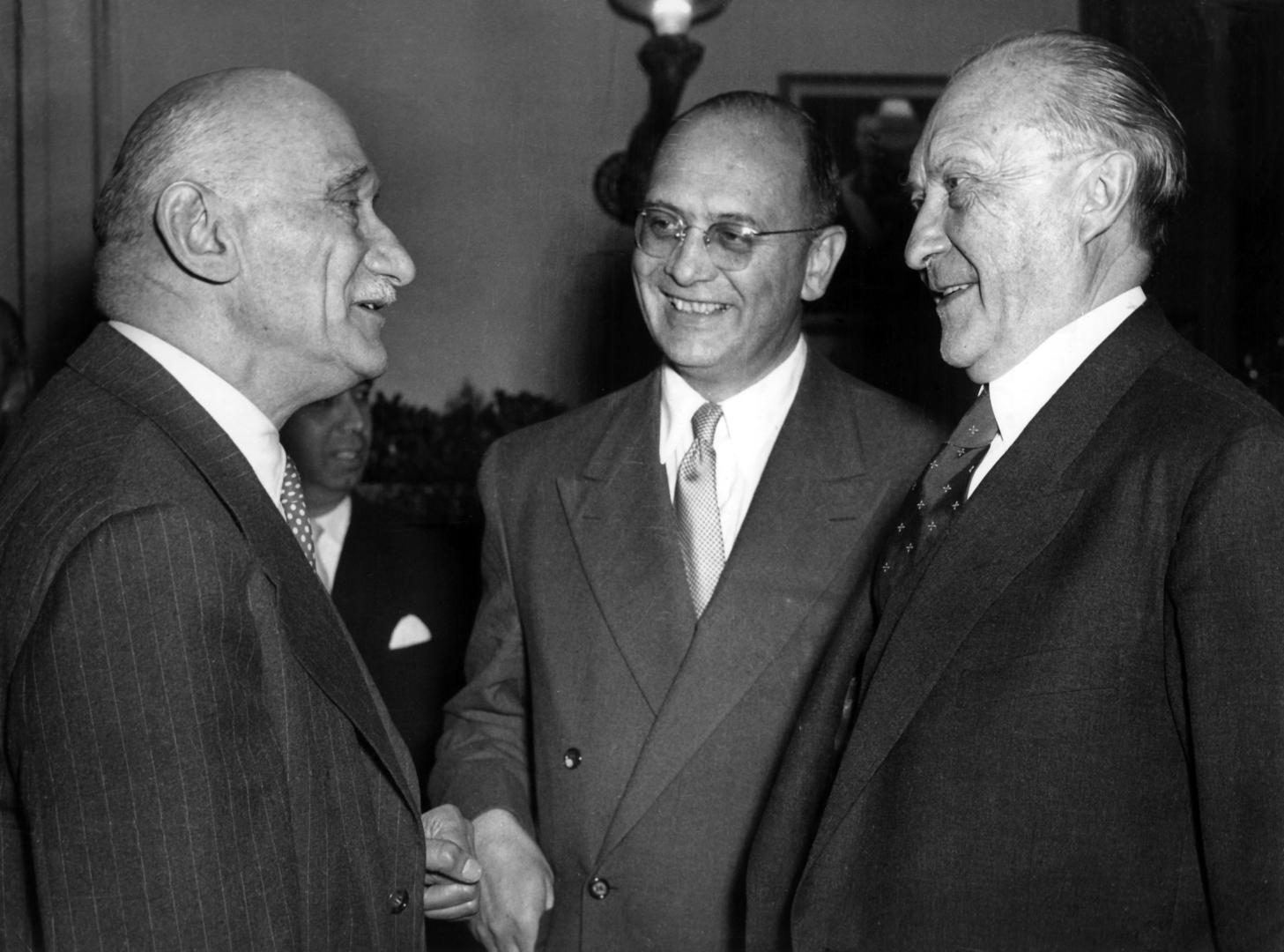

When Konrad Adenauer was elected federal chancellor, sovereign authority over the new democracy remained with the three high commissioners of the Western Allied powers: the United States, Great Britain and France. The Federal Republic, which was largely dependent on foreign decision-making, virtually had the status of a protectorate, although for a long time it remained uncertain whether the Western powers would treat the newly created state as a bargaining chip if negotiations were held on the future of Germany as a whole. In France in particular, there was great concern about the latent power of this ‘western state’ and the instability that might prevail in a divided Germany. Even in the Federal Republic, which was overwhelmed by masses of refugees and had yet to establish a credible identity after division and occupation rule, people were uncertain whether the reconstruction effort really would succeed. Against this background, it is astonishing how by 5 May 1955, when almost unlimited sovereignty was restored, the externally controlled and impoverished German core state in the west had developed the most powerful economy in Europe and had become a democracy supported by broad majority of the population, as well as a powerful player in Western Europe. In the general opinion, the credit for this was due primarily to Adenauer. From the point of view of the Western democracies and a considerable part of the German electorate, he had achieved three crucial goals: firstly, his unassailable position after the 1953 federal election had enabled him to create a strong and lasting foundation for democracy from apparently unstable beginnings; secondly, he had forged an equally reliable bond with the West, which protected the Federal Republic from the Soviet Union in the east while offering its western neighbours security from ‘incertitudes allemandes’; thirdly, his policy of rapprochement with the West and his willingness to integrate with it had restored Germany’s political and moral credibility.

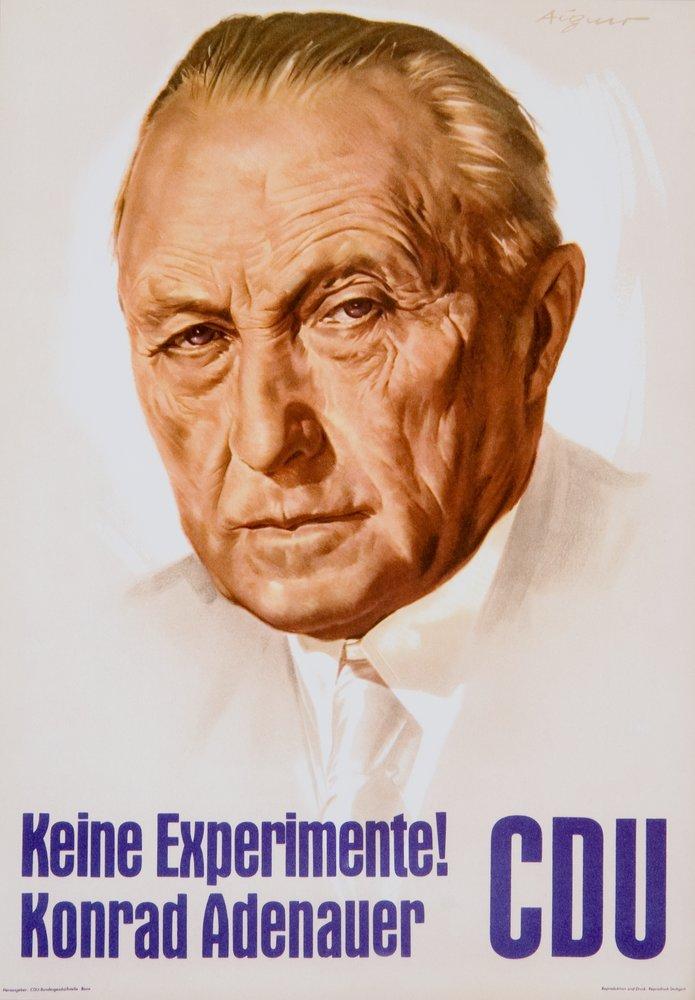

The Adenauer CDU as the ‘Party of the Federal Republic’

Konrad Adenauer began his post-war career as a party leader and, to a great extent, he continued to see himself as a party leader after taking office as chancellor. The CDU, in the form that it acquired during the 1950s, was both his work and his tool. Coming from the Catholic Centre Party and with deeply held religious convictions, Adenauer had advocated an interdenominational mainstream political party long before, when he had presided over the 1922 Catholics’ Day festival in Munich. It was mainly thanks to his skill as a leader that the CDU, which arose in 1945 in conjunction with the CSU, became the strongest political force in the Federal Republic, that it largely identified with West Germany as the core German state as well as with the corresponding political course set by Adenauer, and that it stabilised the Federal Republic by following a moderately conservative ideology that was business-friendly while balancing the interests of different parts of society. Thus it was not the SPD, which could boast of a long democratic tradition, that was perceived as the party of the Federal Republic during the Adenauer era – years that were crucial to the country’s later development – but the CDU, then still strongly Christian, but with pro-Western, modern domestic and foreign policies.

Establishing a Social Market Economy

Before German currency reform in 1948, influential groups within the CDU were pushing for society and the economy to be developed along socialist lines to a greater or lesser extent. Adenauer, in contrast, supported the principle of the market economy, in combination with social welfare and a system of checks and balances. He convinced the CDU to accept Ludwig Erhard, a neo-liberal who was not actually a member of the party, as Minister of Economic Affairs and he kept the ‘father of the economic miracle’, as Erhard later became known, in the cabinet until 1963. Adenauer himself fluctuated between the policies of a free market economy (in terms of wages, taxation, trade unions and housing) and policies associated with state intervention and social welfare (on energy, agriculture, the compensation fund for wartime losses, index-linked pensions and state subsidies). All in all, however, during his period in office, the Federal Republic clearly developed along the lines of a market economy with high growth rates, the lifting of protectionist trade barriers, booming exports, a stable currency and weak trade union influence.

The Invention of Chancellor Democracy

The term ‘Kanzlerdemokratie’ first appeared after the national parliamentary election of 1953, when Adenauer won the first of his landslide victories. The institutional prerequisites for a chancellor-led democracy were, in fact, already enshrined in the Basic Law. Adenauer made the greatest possible use of this potential. As with other chancellors after him, the extent of his power was determined by the fact that he held both the office of chancellor and the chairmanship of the strongest governing party. This dual power meant that Adenauer always had the upper hand in disputes with members of his cabinet, the leaders of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, or his coalition partners, as well as in disputes with the CSU, the regional branches of the CDU, or even the governments of the federal states. In essence, Adenauer ran the CDU from the Federal Chancellery, which was reflected in the campaign slogan: ‘It all depends on the Chancellor!’ Adenauer valued the thorough, argumentative and objective discussion of each issue with the ministers of his cabinet, but his style of government was generally authoritarian, including his treatment of them. In his dealings with smaller coalition parties, he relied less on compromise and consensus than on conflict. The Adenauer era is therefore also the story of countless coalition crises, which the chancellor tried to provoke rather than avoid, as a means of achieving his goals. From 1949 to 1955, the political constellation in Germany worked in Adenauer’s favour. Until the return of German sovereignty, all contact with the Allied High Commissioners and the Western governments ran through him. He was his own foreign minister from 1951–55 and was therefore able to promote his policies in person during the early days of European integration. Also under his direct control was the bureau headed by Theodor Blank, which was responsible for preparing West Germany’s defence contribution until 1955. The Federal Press and Information Office was another area in which he tolerated no interference from others. His position of superiority was reinforced by respect for his age and experience. In addition, Adenauer knew how to keep those who had political dealings with him in their place, and he did so in a haughty, ironic and often hurtful way. All in all, however, he got the German public, which was still fixated on authority – more than it would be in later years – used to the idea that democracy and governmental authority are not opposites, but the ideal complement to each other.

Alignment With the West

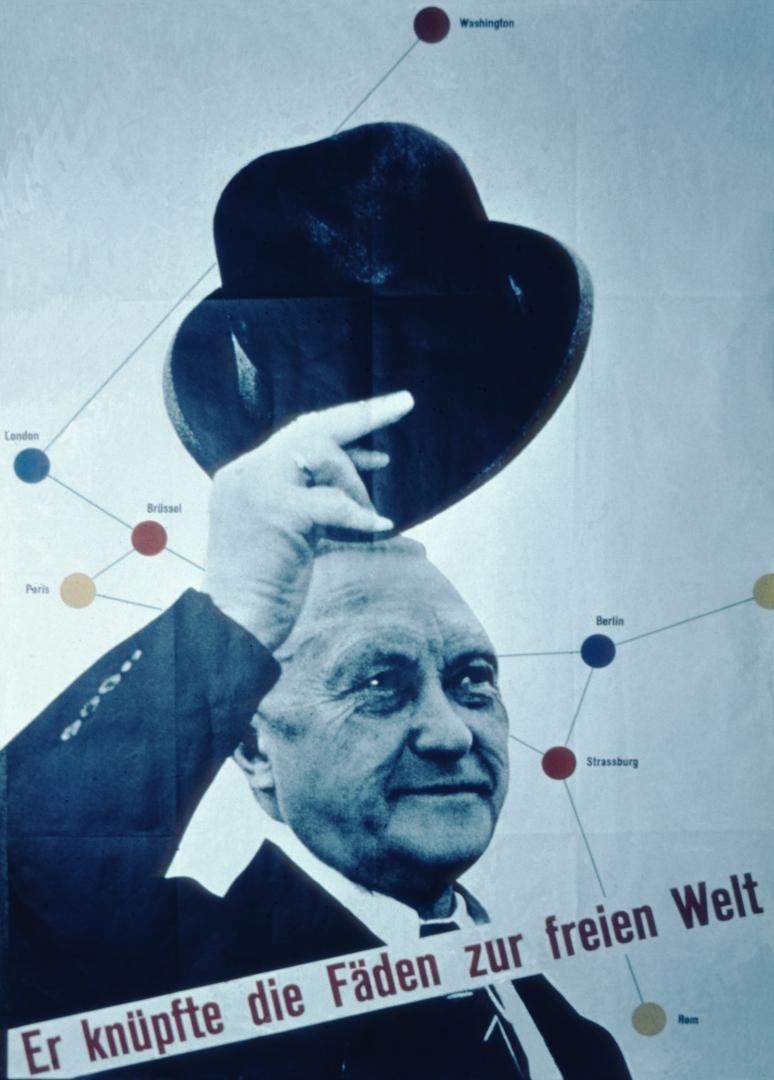

After the Second World War, Konrad Adenauer lived in constant fear that the Soviet Union might expand yet further. Anti-communism, rooted in liberal Christian convictions, was one of his strongest motives in politics. He thought that it would be a mistake for Germany to adopt a wait-and-see approach or a mediating role in the East-West conflict; instead he advocated unconditional ties to the West, first for the western occupation zones, then for the Federal Republic. This served both the quest to regain Germany’s freedom of action (at least with regard to the Western powers) and the desire for protection by them, especially by the United States. Under these circumstances, he considered that a deepening of the division of Germany was an acceptable price to pay. In essence, Adenauer saw the democracies of the North Atlantic sphere as an ideal unit. Once his own position had been consolidated, he never hesitated to play off the three Allied powers against each other from time to time as necessary, albeit cautiously. On the whole, however, he tried to avoid unilateral options, mostly following American leadership – at least until the early 1960s, when disappointment with the British and American policies on Berlin and Germany as a whole led him to turn increasingly to the French under President Charles de Gaulle. In any case, he had been convinced from the outset that Franco-German reconciliation was essential. This manifested itself in his unconditional adoption of the Schuman Plan and in the long collaboration – not unconditional, but long pursued with commitment – on the plans launched and incessantly reformulated by France for a European Defence Community (EDC). Its failure to gain ratification in Paris in 1954 opened the way for West Germany to make a ‘defence contribution’ within the framework of NATO. Even before de Gaulle came to power in 1958, after the Saar question had been resolved in favour of Germany, Adenauer had assigned a privileged status to Franco-German cooperation within the framework of the ‘inner six’ (France, Italy, the Benelux countries and the Federal Republic of Germany) at the negotiations to establish the European Economic Community (EEC). This included the goal of producing nuclear weapons in trilateral cooperation between France, West Germany and Italy. The relationship with France became ever closer up to the signing of the Elysée Treaty on Franco-German cooperation in 1963. Adenauer remained wary of the French government’s motives nevertheless, as he did in every area of foreign and domestic policy. The perennial efforts to increase cooperation were therefore accompanied by a long series of controversies.

To begin with, Adenauer took an open-minded approach to Great Britain, despite the affront of being dismissed as Lord Mayor of Cologne. He did so partly because of its status as a world power, although British influence waned over the decades of his chancellorship. London’s unwillingness to participate in various projects that served the policy of closer European integration (ECSC, EDC, EEC, Euratom) led him to strive more and more for closer cooperation with France. One of the main motives for his policy of alignment with the West was his determination that the Federal Republic should establish armed forces of its own, which could defend it against the Soviet Union’s Red Army and the East Germans’ NVA, and which would be integrated with the defence organisations of the West. At first, this got him into fierce arguments at home with the Social Democrats (SPD) and with the centrist All-German People’s Party led by Gustav Heinemann. The entire policy of alignment with the West had to be pushed through in the face of constant opposition from the SPD, which objected to every such treaty with the criticism that it would cement the division of Germany and widen the gulf between East and West. In addition to the question of security and the need to restore access to global markets for German industry, subject to the approval of the Western powers, Adenauer thought it essential to integrate the Federal Republic with the Western democracies as closely as possible, not least as a means of safeguarding its own development as a democracy.

Policy on Germany as a Whole

Konrad Adenauer conceived the Federal Republic as the core German state in sole legal succession to the German Empire – a stance that he maintained steadfastly up to the end of his chancellorship. This did not preclude him from having modifications to this principle explored internally at intervals from the mid-1950s onward, especially under the pressure of the Berlin crisis. Since Soviet policy remained expansionist, however, he considered it advisable first to consolidate West Germany and Western Europe with the support of the United States. Only after that, in his estimation, at some point when the circumstances would be favourable, could a solution to the German question be reached through reunification and perhaps even an adjustment of the eastern borders. There has been strong criticism that Adenauer gave higher priority to safeguarding freedom, re-emergence and prosperity through ties with the West than to risky reunification policies. In retrospect, however, Adenauer’s restraint over the division of Germany turns out to have been one of the most important contributions to stabilising the Federal Republic and the Western European state system. Nevertheless, this system held an inherent risk of war and it remained unstable during Adenauer’s lifetime owing to unilateral pressure from the Soviet Union, as shown by the Berlin crises in the period from 1955 to 1962. Adenauer’s course of unconditional alignment with the West was in line with his determination not to accept any proposal to reunify Germany as a non-aligned state. He insisted that a unified Germany should at least have the freedom of choice when it came to alliances and European integration.

The Stabiliser of Europe

From an historical point of view, Konrad Adenauer deserves the accolade of a ‘great European’ on two grounds. Firstly, by adhering to Western alignment as a key policy, he helped to stabilise the precarious situation in Germany, caused by its division and the absurd status of West Berlin. Since the former German Empire had played a leading role in the destruction of the European state system, the political course steered by this chancellor – one of balance and integration with the countries to the west – was considered to be a great feat of statesmanship. This alone is sufficient to count him among the most important ‘stabilisers of Europe’. The second reason is that he sought to promote the integration of Western Europe – and did so with remarkable openness, dynamism and foresight. From an initially precarious position, he found ways of taking on board what was offered in each case and modifying it to serve German interests: accession to the Council of Europe, the Schuman Plan, the European Defence Community (EDC), proposals for a European Political Community (EPC), plans for a European customs union (from which the European Economic Community emerged after negotiations between six countries), French proposals for a European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), and de Gaulle’s push to establish a political union. Despite his advanced age and his political upbringing in the era of empires, Adenauer showed astounding optimism and willingness to experiment in the creation of institutions that, while offering a path to a better future, were quite untested. Yet he did so without getting himself committed to any particular concept for Europe. In this respect, too, he remained less a visionary than a pragmatist who was keen to experiment. In any case, his determination to anchor the Federal Republic firmly in the West European communities was one of his most important contributions to the history not only of the Federal Republic, but also of Europe. Of all the statesmen who worked to unify Western Europe in the decade after the war, he was the most important.

Adenauer the Moderniser

The Adenauer era was criticised as a period of backward-looking ‘restoration’ during his lifetime and afterwards, both by the far left and by the Christian socialists who Adenauer had sidelined within the CDU. Marxist accusations of revanchism and the like need not be taken seriously. The social market economy introduced by Adenauer and Erhard embodied a concept of capitalism tamed by the requirements of political order and social welfare. It is certainly true that, as chancellor, Adenauer liked to rule in an authoritarian way. Having risen through society during the decades of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, and being not without arrogance, he undoubtedly brought with him an understanding of government in which the holders of high office are granted the freedom to decide things themselves and the authority to issue orders – subject to achieving a majority in a coalition cabinet, in parliament, or at a general election. It was in this ultimately democratic understanding of political office that Adenauer differed from the empire’s governing principle of subordination to higher authority. Rearmament led to the accusation that he was restoring militarism, but this was completely untrue. In no other area of public life was the loyalty of the middle and higher ranks to democracy subjected to parliamentary checks as stringent as those for officers who had formerly served in the Wehrmacht. During Adenauer’s time in office, the civilian control of the new army, the Bundeswehr, through political and bureaucratic institutions was of unequalled stringency. It is true that Adenauer sought to oppose Soviet power politics with a Western counterweight. This aspect of ‘restoration’ in maintaining the balance of power was raised mainly by the communist camp, but also by the advocates of more or less unconditional pacifism. In reality, the Federal Republic as a society was in a state of continual modernisation throughout the Adenauer era – and in the person of Adenauer, it had a determined moderniser at the helm in the Federal Chancellery. He was the type of moderniser – keen on technology, willing to make changes, without ulterior motives, open to innovation of any kind – that had appeared during the industrial boom in the empire and continued in the Weimar Republic, even surviving the Third Reich. Adenauer, as was widely known from his time as the Lord Mayor of Cologne, was one of those idiosyncratic, daring movers and shakers from whom modern German society derived its dynamism. Many of the achievements outlined above can be seen as the work of a moderniser: the shifting of outmoded party divides through the creation of the CDU; the establishment and expansion of chancellor-led democracy; the sustainable continuation and fostering of cutting-edge technologies – not least of nuclear power – that had been interrupted during the Allied occupation; the modernisation of agriculture in the ‘Green Plans’; motorway construction, and house-building. Of the areas in which the federal government could take action, there were few that did not undergo fundamental modernisation during the 1950s and 1960s. Adenauer also proved to be a moderniser on a higher plane when it came to making a wholehearted contribution to European unification projects of unprecedented scope. Doubts only troubled him towards the end of his life, when he realised how profoundly the technical innovation that he had unleashed alongside material prosperity had undermined the generally accepted religious value systems, the work ethic and the individual appetite for excellence, as well as disfiguring familiar landscapes and buildings. Even before stepping down as chancellor, and afterwards ever more loudly, he began complaining about ‘the chaos of values’, worldwide ‘disorder’, the decline in religious observance and patriotism, the breathtaking restlessness of modern life, and the dissipation of creative energy. He thus found himself ultimately overtaken by the contradictions and the unintended side-effects of a modernisation process that he himself had promoted throughout his life.

The original german text was translated into English by Richard Toovey.

Collection: Stiftung Bundeskanzler-Adenauer-Haus Rhöndorf.

Curriculum vitae

- 1894 Graduation from the Aposteln high school, Cologne

- 1894–97 Law studies in Freiburg, Munich and Bonn

- 1897 First state examination in law, legal traineeship

- 1901 Second state examination in law

- 1903–06 Examining magistrate in the Cologne public prosecutor’s office, work in a legal practice, assistant judge at the regional court of Cologne

- 1906–09 Alderman of the City of Cologne

- 1909–17 First Alderman

- 1917–33 Lord Mayor of Cologne

- 1921–33 President of the Prussian State Council

- 1933 Dismissed as Lord Mayor by the National Socialists

- 1933–34 Stay at the Benedictine monastery of Maria Laach in the Eifel region

- 1934–35 Neubabelsberg

- from 1935 Resident in Rhöndorf

- 4 May 1945 Reinstated as Lord Mayor of Cologne by the Allied occupation forces, subsequently dismissed

- 22 Jan 1946 Elected provisional leader of the CDU of the British zone, in Herford

- 1 March 1946 Elected leader of the CDU of the British zone, in Neheim-Hüsten

- 1946–50 Member of the state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia

- 1946–49 Chairman of the CDU parliamentary group in NRW

- 1948–49 President of the Parliamentary Council

- 1949–63 Federal Chancellor

- 1949–67 Member of the national parliament (Bundestag)

- 1950–66 Chairman of the CDU at national level

- 1951–55 Federal Foreign Minister

- 1966–67 Honorary chairman of the CDU