Overview – Skip to a certain paragraph:

☛ Minister President of Baden-Württemberg

☛ Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

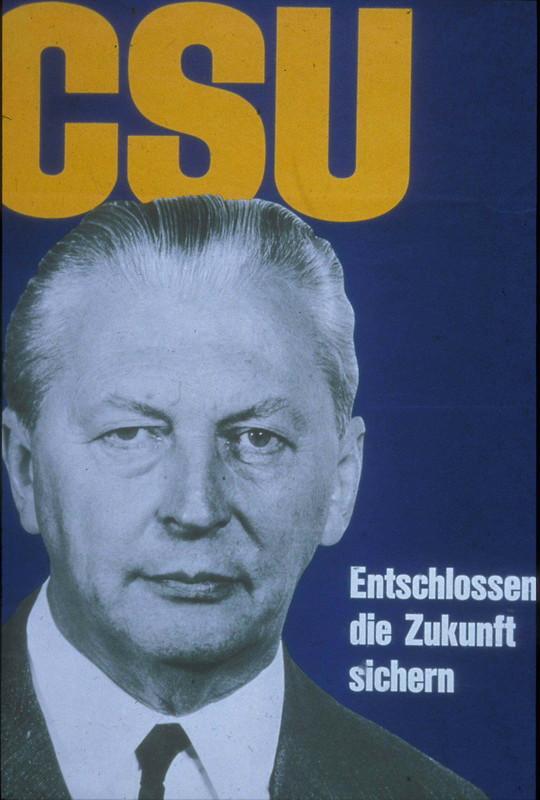

Kurt Georg Kiesinger was one of the most popular chancellors of the Federal Republic, according to contemporary opinion polls. At the head of a grand coalition, envisaged as a temporary alliance between the CDU/CSU and SPD, he presided over a cabinet that included almost all of the political heavyweights of that time, with the exception of the leaders of the two respective parliamentary groups, Rainer Barzel and Helmut Schmidt. The grand coalition introduced legislation of major importance and Kiesinger, the great mediator between partners and rivals, played a key role in the sweeping reforms of the late 1960s. The fact that, toward the end of his term, Kiesinger was viewed almost as a relic of a bygone age, is less a reflection of personal failure on the part of the 'forgotten chancellor' than a symptom of the rapid shift in public opinion and political culture over the years of the ‘1968 revolution’.

By virtue of his background, political socialization and career, Kiesinger was predestined to play the role of the archetypal mediator in German post-war politics. As early as the 1950s, he was looking for ways to accommodate and reconcile the interests of different political parties. For example, he advocated allowing the opposition to participate in the election of judges to the Federal Constitutional Court. Kiesinger himself attributed his skills as a mediator to having grown up in the Swabian Alb: a region divided among various religious denominations and clans. As if that weren't enough, he himself was raised by parents of different faiths, in view of which he later liked to call himself a 'Protestant Catholic'. Kiesinger was sometimes viewed as being out of touch with the times, partly because of his refined, academic bearing and his inner detachment from the day-to-day business of politics. Mostly, however, it was due to his membership in the NSDAP and his service, from 1940 onward, in the Foreign Office, where he eventually became deputy chief of the broadcasting policy department, which was responsible for propaganda outside Germany. This explains why, during the growing polarization of the 1960s, he became a symbol of a past that Germany had yet to come to terms with. The fact that Kiesinger, a staunch democrat, also embodied the transformation of political culture in Germany, from National Socialism to democracy, was given scant consideration in the heated atmosphere of the time. He did have some steadfast defenders among the victims of the Nazi regime, however, and they considered him an example of productive engagement with the legacy of the Third Reich. To them, his collaboration with SPD politicians Willy Brandt and Herbert Wehner, who had been active in the resistance, was viewed as evidence of the reconciliation of historical opposites.

Member of the Bundestag

Kiesinger had originally aspired to a career as a lawyer or an academic – options denied to him after 1933 – and was not part of the new order of politicians that took over in 1945. He entered politics as a result of his friendship with the CDU chairman for what was then the state of Württemberg-Hohenzollern, Gebhard Müller, who asked him to be the party’s general secretary in that state. Kiesinger held that office until 1951. Nor did he run for a seat in the Bundestag at first, although he was later elected to that body with one of the highest majorities ever. An accomplished speaker, Kiesinger attracted the attention of Adenauer and was soon numbered among the elite in the new parliament.

Owing not least to his rhetorical talent, he was one of the CDU’s high-profile representatives in Bonn, first as a legal expert and then, increasingly, as a foreign affairs specialist. Among the younger members of the parliamentary group – he himself was one of the very few members in their forties – Kiesinger was considered a rising star. But he remained no more than a ministerial hopeful until 1958. Before leaving Bonn for Stuttgart, he was unable to gain a government office. This was due in part to his complicated relationship with Adenauer, whose policy of alignment with the West he defended in brilliant speeches. Back in 1949, at one of the very first meetings of the CDU parliamentary group, Kiesinger had quarrelled with Adenauer over the candidacy of Theodor Heuss for the office of Federal President. In characteristic fashion, Kiesinger had wanted to fill the highest office of state through consensus among the major parties.

Kiesinger's failed candidacy for the office of CDU general secretary at the 1950 national party convention in Goslar and other disputes in the following years may have strengthened Adenauer's doubts about his absolute loyalty and his appetite for power. Kiesinger was repeatedly passed over in cabinet reshuffles, up to and including the formation of Adenauer's third government in 1957. He was not interested in being fobbed off with an ambassadorship or a comparatively minor ministry. The lack of a cabinet appointment was partly due to chance circumstances and to the trade-offs needed within a coalition, but above all Kiesinger lacked a power base because of the fragmentation of the CDU in south-western Germany, although he had been one of the staunchest advocates of the merger of smaller states that had formed the Land of Baden-Württemberg.

Minister President of Baden-Württemberg

Given this background, it was natural that Kiesinger would accept the offer to become minister president of Baden-Württemberg. He did not give up his ambitions for federal office after moving into his official residence at Villa Reitzenstein, but in retrospect, the Stuttgart years were his most successful as a politician. Kiesinger was considered an outstanding figure among the minister presidents of the Länder, and in the late 1950s, significant opportunities opened up for policy makers at the state level. During Kiesinger's term of office, Baden-Württemberg was 'deprovincialized': its largely agrarian structure was overlaid with a flourishing network of industrial centres. In education policy, Kiesinger took the lead among reformers by creating the University of Konstanz (established by 'royal decree', as some commentators later opined) and expanding the universities of Ulm and Mannheim. In the realm of German research and academia, Kiesinger is also credited with the establishment of several large institutes, such as the South Asia Institute in Heidelberg and the German Cancer Research Centre. As minister president and state 'paterfamilias', he oversaw a virtual explosion in road building and urban growth, accompanied by planning for long-term development and land-use. For the first time, this contained extensive provisions for protecting natural resources and cultural assets, which came into play, for example, in the controversy over making the Upper Rhine navigable. In the Bundesrat, Kiesinger occasionally took positions opposed to the federal government, as in the case of the dispute over the broadcaster ZDF, regarding the role and status of public television. From his base in Stuttgart, he even managed to maintain a limited involvement in foreign policy. As the president of the Bundesrat, for example, he travelled to meet President John F. Kennedy. As West Germany’s commissioner for cultural affairs, he took part in intergovernmental consultations under the Franco-German Treaty of 1963. In the other direction, his move to Bonn released Kiesinger from the need to make a decision of conscience in the dispute involving South Württemberg's denominational schools. Nor was he directly involved in the squabbles about Adenauer's succession. He was therefore relatively unencumbered when his party resolved to select a new chancellor candidate in 1966, which allowed him to garner broad support and to prevail against his rivals Rainer Barzel, Eugen Gerstenmaier and Gerhard Schröder.

Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

Kiesinger's accession to office was overshadowed by foreign and domestic crises. In a surprisingly brief time, however, his government managed to consolidate public finances, set a new course in West Germany's Ostpolitik, and repair the country's relationships with France and the United States. At the same time, it implemented enduring reforms to improve the economy and finances of the Federal Republic, and to modernize a broad range of laws and judicial procedures. Kiesinger's interest was primarily in foreign policy, but as a consensus politician – in one commentator’s words, the “moderator Germaniae” – he shared credit for implementing more than four hundred pieces of legislation in many different fields.

As chancellor, Kiesinger has not gone down in history as one of the very great figures, in part because the change in the balance of power that the SPD engineered after the election of September 1969 cast him in the role of loser, despite obtaining a very good electoral result for the CDU/CSU. Kiesinger had underestimated the rapprochement between the SPD and FDP as friction grew in the coalition from early 1968 onward. He also made mistakes in internal party affairs, despite his election as national party chairman in 1967. Kiesinger was unable to exert effective control over the party and the parliamentary group, as can be seen from Gerhard Schröder's candidacy for the office of Federal President, and the ability of Franz-Josef Strauß to prevent the signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Once he had lost the office of Federal Chancellor, Kiesinger's career was practically over. Even as CDU chairman, he was living on borrowed time. He no longer had the ability (and the desire) to join in the power struggles within the party, and he played an unfortunate role in the debates on treaties with various Eastern European states. Kiesinger remained a member of the Bundestag until 1980, after which he returned to Tübingen.

The original german text was translated into English by Richard Toovey.

Curriculum vitae

- 1919–25 Teacher training at the Catholic seminary in Rottweil

- 1925–26 Student of education at the University of Tübingen

- 1926–31 Student of German philology, history and law in Berlin

- 1931–34 Junior lawyer

- 1934–45 Private teacher of law and lawyer in Berlin

- 1940–45 Research assistant and deputy head of the broadcasting policy department at the Foreign Office

- 1945-46 Internment in Ludwigsburg

- 1946–50 Private teacher of law in Würzburg and lawyer in Rottenburg and Tübingen

- 1948–51 General secretary of the CDU in the state of Württemberg-Hohenzollern

- 1949–59 and 1969–1980 Member of the Bundestag

- 1950–57 Chairman of the Mediation Committee

- 1954–58 Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee

- 1950–58 Member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

- 1955–58 Vice-president of the Parliamentary Assembly

- 956–58 Chairman of the Christian Democrat group in the Parliamentary Assembly

- 1958–66 Minister President of Baden-Württemberg

- 1960–66 Member of the Landtag (state parliament) of Baden-Württemberg

- 1963–66 Federal Republic commissioner for cultural affairs under the Franco-German Treaty

- 1966–69 Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1967–71 National chairman of the CDU

- 1971–88 Honorary chairman of the CDU