Overview – Skip to a certain paragraph:

☛ Market Researcher and Economic Adviser

☛ Initial Thoughts on Peacetime Economy

☛ Minister of Economic Affairs and Vice-Chancellor

☛ Forward-Looking New Policies

☛ Advocate of a Liberal Social Order

Formative Years

Like Margaret Thatcher, who was a generation younger, Ludwig Erhard spent his childhood ‘above the shop’. In his case, it was a shop for household linens in Fürth, a business established from modest beginnings by his Catholic father and Protestant mother, who were supporters of Eugen Richter, a liberal member of parliament and journalist. Erhard attended a secondary school that prepared children for vocational training, after which he completed a commercial apprenticeship in Nuremberg. Then, however, the First World War diverted him from his intended path. When Erhard enlisted in the armed forces, he was already suffering from the long-term effects of a childhood polio infection. His health was then further impaired just prior to the end of the war, when he incurred an injury so severe that it forced him to look for a new career. In view of the secondary school he attended, Erhard had never sat for the Abitur, the exam normally required as a qualification for university admission in Germany. He therefore enrolled in a business studies programme at the recently founded business college in Nuremberg. It was there that he met the business economist Wilhelm Rieger, who would become a major influence.

Soon afterwards, Erhard married his fellow student Luise Schuster (née Lotter), a war widow with a daughter. Together, the couple had another daughter. In 1922, he completed his business studies programme, earning the title Diplom-Kaufmann, and subsequently studied economics in Erlangen and Frankfurt am Main. He completed his academic studies in 1925 by obtaining a doctorate under the economist and sociologist Franz Oppenheimer – an independent, well-rounded thinker who advocated the mutable concept of ‘liberal socialism’.

Market Researcher and Economic Adviser

In the next few years, Ludwig Erhard tried to stabilise the family firm, which had been severely impacted by inflation. These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. In 1929, he turned to economics research again and joined the Institute for Economic Observation of the Finished Goods Industry (Institut für Wirtschaftsbeobachtung der deutschen Fertigware), which had been established by Wilhelm Vershofen at the business college in Nuremberg. Gradually, he took on management positions at the Institute and, in 1934–35, also became co-founder of the Society for Consumer Research (Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung). In addition to the editorial work, teaching and business development that Erhard pursued for the Institute during these years, he was also occupied with market analyses for the consumer goods industry, which had deep roots in Franconia. As the economic planning of the Nazis began to affect a larger share of the economy, he worked on structural analyses of other sectors, too.

During the Second World War, the analyses composed by Erhard dealt especially with economic structures in the region of Saarpfalz and in the French-border area of Lorraine, which had been occupied since 1940, as well as the German-occupied areas of Western Poland (annexed in 1939). In the course of providing these reports to clients, he sometimes interacted with agencies and personnel of the Nazi state and party apparatus, such as Josef Bürckel, who at this time held the positions of Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter (terms for political officials governing districts under Nazi rule), and Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, who for a time served as Reichskommissar (Reich commissioner) responsible for price controls, and who later recommended Erhard to conservative members of the resistance as an adviser on economic policy. Given the facts of Erhard’s conduct during the Nazi period, he can neither be celebrated as an active member of the resistance nor branded an immoral profiteer. Like millions of his contemporaries, he adopted habits of external conformity and self-preservation, and in his studies, he sometimes had to be considerate of his clients from industry and government. But there can be no doubt of his growing, inner distance to National Socialism. Evidence of this can be found in a preliminary report on ‘The Economy of the New German Territory in the East’ (Wirtschaft des neuen deutschen Ostraumes), which was written in July 1941 and has been studied and critiqued numerous times since then. The surviving abridged version, created by the Main Trustee Office for the East (Haupttreuhandstelle Ost) of the Office of the Four-Year Plan, reveals that Erhard advocated treating Polish workers well and recommended improving the economic conditions of the Polish population. Making strictly economic arguments in his role as an expert, Erhard displayed a provocative level of self-confidence and perhaps even a dangerously carefree attitude in defying the expectations of Nazi racial policy, which dictated an uncompromising Germanisation of the Polish territories.

Initial Thoughts on Peacetime Economy

Since Ludwig Erhard refused to join Nazi organisations, it was clear that he would not be able to obtain a qualification as a university lecturer and pursue a career in higher education; nor would it be possible for him to succeed Vershofen as director of the Institute for Economic Observation of the Finished Goods Industry. In 1942, he therefore left the Institute on a disharmonious note. With financial support from the Reich Group Industry (Reichsgruppe Industrie), which was headed by his brother-in-law Karl Guth, Erhard set up the small Institute for Industrial Research (Institut für Industrieforschung). Continuing after the war, it was one of the precursors of the ifo Institute for Economic Research (ifo-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung) founded in 1949. Its primary task was to draft plans for post-war economic reconstruction in respect of Germany’s industrial sector. The most important of the documents commissioned from the Institute for Industrial Research was a study titled ‘War Finances and Debt Consolidation’ (Kriegsfinanzierung und Schuldenkonsolidierung) completed in 1944. In his subsequent work, Erhard proceeded from the assumption that it would be necessary to relax the price controls of the wartime economy. Deliberations of this sort on the subject of a peacetime economy, which tacitly presupposed total defeat – an outcome that seemed increasingly likely – were strictly prohibited, officially, but the Reich Ministry of Economic Affairs nevertheless approved of them. In November 1944, Erhard had a brief conversation on this topic with the Deputy State Secretary in the ministry, SS Group Leader (Gruppenführer) Otto Ohlendorf, who was open to market-based considerations, in sharp contrast to the Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production, Albert Speer. The war would soon be over, and nothing came of this episode, but it does highlight the strands of continuity that ultimately extended from the old Reich Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Reich Group Industry to the future Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs. These were continuities not only of personnel but of policy, as evidenced by the residue of Nazi-era economic legislation that remained in effect in the Federal Republic for decades in the form of special, anti-competitive rules and regulations.

As far as Erhard’s intellectual biography goes, however, it is striking to what extent the debate involving the planned economy and war financing of the Nazis influenced his economic thinking, which evolved into an affirmation of market economics and became more refined and more rigorous politically. Based on the more practical perspectives of business administration and market research, his regulatory and competition policy thinking consolidated on quite independent paths. It was only after 1948 that he developed closer personal connections to other advocates of the emerging creed of neoliberalism. By the end of the war, Erhard was entirely convinced that a framework of economic liberalism not only offered the best possible conditions for supplying the population with goods of all sorts, but was also the prerequisite for ensuring human dignity and self-respect.

The Reformer

After the war, Ludwig Erhard offered his services as an advisor to the American occupying forces in his home town of Fürth. As early as September 1945, they unexpectedly selected him as Minister of Economic Affairs in the Bavarian government under Minister President Wilhelm Hoegner, a Social Democrat. However, owing to a lack of party-political affiliation, he left the state government, now organised along parliamentary lines, after the first Landtag election in December 1946. Erhard was a Protestant from Franconia and would avoid making the mainly Catholic CSU his political home for the rest of his life. His subsequent post as an honorary professor at the University of Munich was some compensation for his loss of political office, but it was his appointment, in September 1947, as head of the newly created Special Office for Money and Credit (Sonderstelle Geld und Kredit) that would set the course of his future career. This office was charged with overseeing preparations for the currency reform needed in the unified economic area of the American and British zones of occupation.

In March 1948, at the suggestion of the CDU and FDP – and despite the resistance of the SPD – Erhard was elected director of the Economic Council of the Bizone (as the combined American and British zones of occupation were called) with a small but significant majority. In this role, Erhard not only oversaw the long-planned currency reform of 20 June 1948, but also introduced market-oriented economic reform when – literally overnight – he abolished price controls on a wide range of goods. After years of ‘pent-up inflation’ (Wilhelm Röpke), the prices of many scarce goods necessarily skyrocketed, as a result of which Erhard encountered much scepticism and bitter resistance. But not even a general strike instigated by the trade unions was enough to unsteady him. With characteristic self-confidence, he kept to the course that he had embarked upon and defended it against the dirigiste thinking that was widespread at the time in both the SPD and the CDU/CSU.

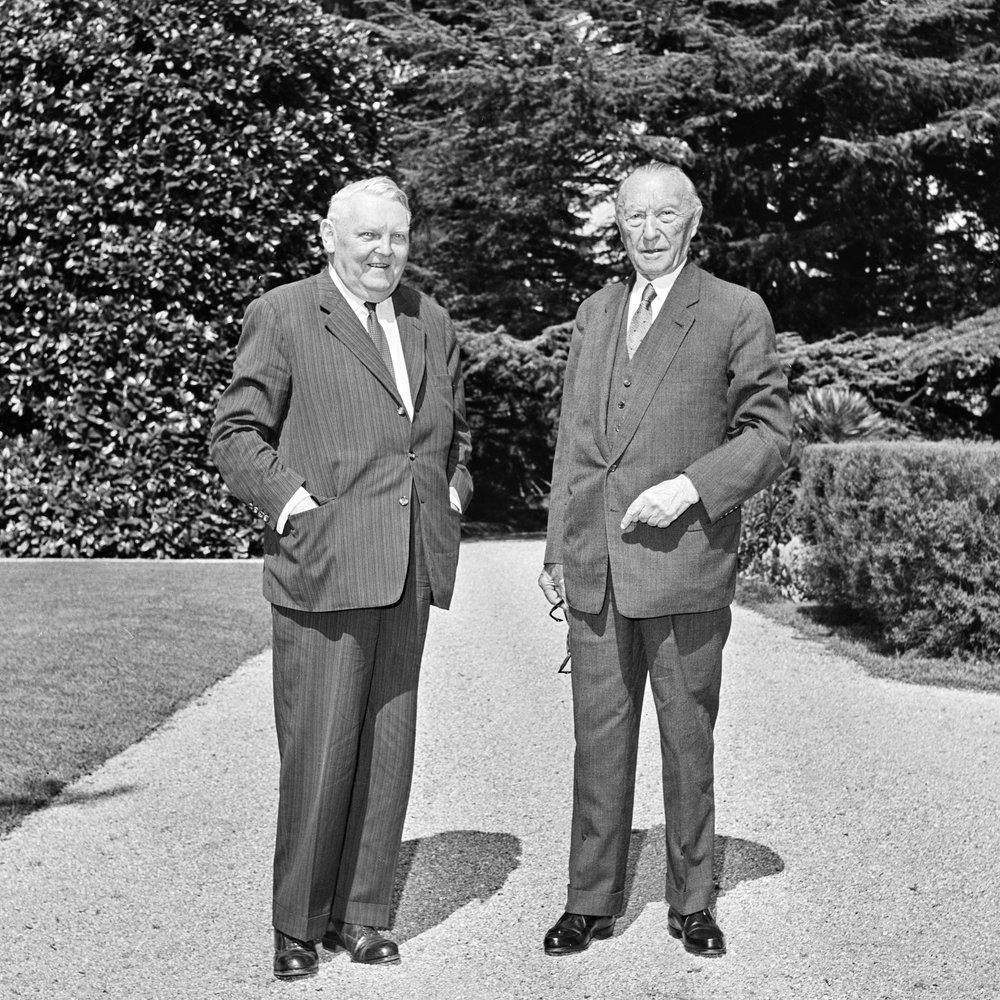

Minister of Economic Affairs and Vice-Chancellor

The course of future events was laid when Konrad Adenauer, chairman of the CDU in the British zone of occupation, made the strategic calculation to co-opt the politically controversial figure of Ludwig Erhard into his party. At the same time, he committed the CDU and CSU – then drifting without orientation as regards the moral valuation of economic activity – to Erhard’s liberal policies. The main line of attack was thus established for the following Bundestag election, the aim being to form a conservative, centre-right coalition. In the Bundestag election of 1949, the CDU and CSU performed slightly better than the SPD. This result allowed Erhard, who had proven to be a bigger draw than Adenauer himself in the election campaign, to assume the post for which he was cut out: Minister of Economic Affairs. After the historic electoral victory of the CDU and CSU in 1957, he became vice-chancellor as well and emerged as the inevitable heir apparent to the chancellorship, though Adenauer tried very hard to prevent this outcome. In the early years of the Federal Republic, Adenauer and Erhard worked together as complementary leading figures, although they could hardly have been more different – one a political fox, the other an idealistic missionary. Erhard endured stinging rebukes from Adenauer, but he also defied him repeatedly like no other minister.

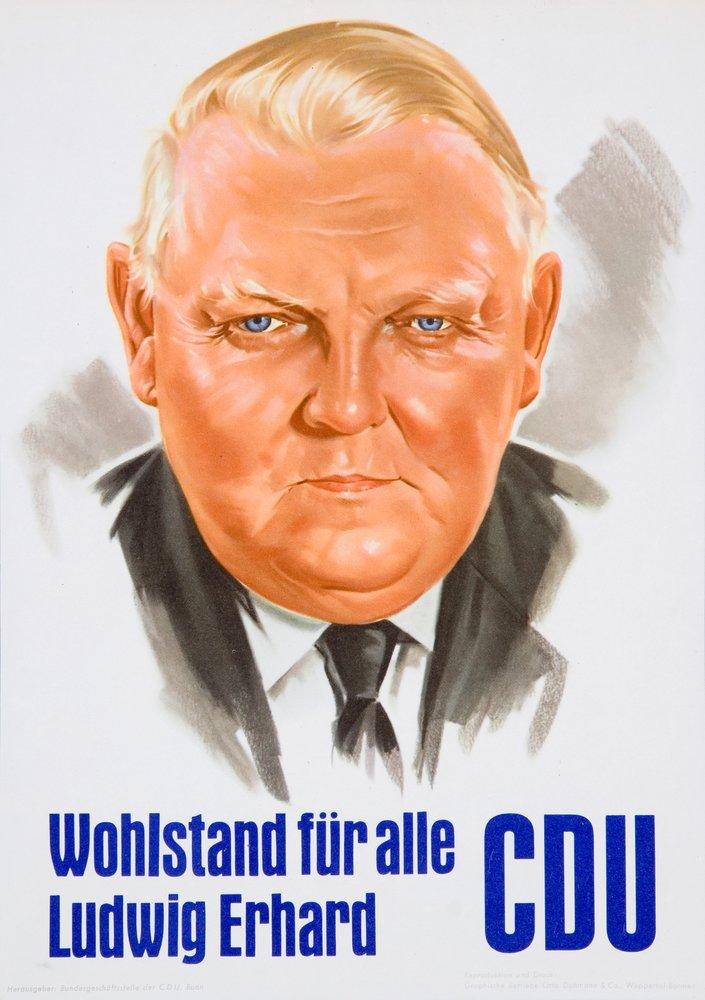

Even apart from the wrangles with Adenauer, Erhard’s career as a minister was by no means perfectly straightforward and preordained. He encountered headwinds almost immediately, in 1950, when the economic turbulence and inflation caused by the Korean War nearly led to his resignation and could have easily ended the daring experiment of the ‘social market economy’ in the process. Erhard would suffer political defeats and failures in later years, too, as in the case of the pension reform of 1957. Overall, however, he proved to be remarkably assertive and persistent in pursuit of his political objectives. In addition to the dismantling of most price controls, and despite some watered-down compromises, further important milestones in the implementation of his political agenda included the creation of an independent central bank committed to currency stability, the Act against Restraints of Competition, fiscal discipline, the integration of the Federal Republic into the system of world trade, and the establishment of social policies that encouraged wealth formation among employees through savings and share-ownership arrangements. It was not least due to Erhard that European integration amounted to more than just a supranational planned economy for the agricultural sector and for the coal and steel industry, rather encompassing liberal moves to create a genuine common market that would be free of state direction. He kept his promise of ‘prosperity for all’ – in German „Wohlstand für alle“, the title of his best-selling book from 1957 – by achieving high rates of growth and full employment. In fact, he did this so successfully that it created problems of its own: in his later years, though celebrated as the ‘father of the German economic miracle’, he ended up with the thankless tasks of fending off excessive demands made of the government by special interest groups and warning against growing materialism and fiscal carelessness.

Ill-Starred Chancellor

With the election of a new chancellor in the autumn of 1963 – a step repeatedly delayed by Adenauer – the young Federal Republic was seen by many observers as having passed an important test and having reached a milestone of stability. Adenauer’s successor, Ludwig Erhard, was expected to bring a more conciliatory governing style with room for dialogue; he aspired to the role of a ‘people’s chancellor’ who would not allow himself to be co-opted by powerful interest groups or political parties. Consequently, he placed his hopes in direct communication with the public and in reason and rapprochement – symbolised by the open, well-lit spaces and clear lines of the bungalow designed for him by architect Sep Ruf in the park of the Chancellery.

His chancellorship was dogged by ill fortune, however. Despite a brilliant victory in the Bundestag election of 1965, it quickly went to pieces for a whole host of reasons: unfinished business from the late Adenauer years in the field of domestic policy; intrigues and feuds of succession within the CDU and CSU; growing estrangement between the CDU/CSU, on the one hand, and the FDP on the other; the transformation of the SPD into a coalition partner attractive to both of the centre-right parties; conflicts over the direction of foreign policy between Francophile ‘Gaullists’ like the party chairmen Konrad Adenauer and Franz Josef Strauß, on the one hand, and Anglophile ‘Atlanticists’ like Foreign Minister Gerhard Schröder and Erhard himself on the other; erratic foreign policy decisions with regard to the Americans and, even more so, the French, in the context of nuclear policy; the decoupling of the unresolved ‘German question’ from moves toward détente between the United States and the Soviet Union; intellectual and cultural upheaval in West Germany on the eve of the tumultuous year of 1968; signs of an impending economic crisis; and, last but not least, the growing dominance of the Keynesian paradigm of interventionist and open-handed economic and social policy. Although it was anything but superficial, his notion of a formierte Gesellschaft (well-ordered society) was ill-fated and failed to provide Erhard with a rousing leitmotif for his chancellorship. Nor did he derive any stability from his belated and rather half-hearted assumption of the chairmanship of the CDU in March 1966. Since he himself was committed to the increasingly unstable coalition with the FDP, his role came to an end in October 1966, when relatively minor budgetary problems triggered the break-up of the coalition.

Forward-Looking New Policies

Although Ludwig Erhard served a short term of office, his administration can be credited with a number of achievements. With respect to foreign and intra-German policy, these included the first border pass agreements with the GDR after the construction of the Berlin Wall, the opening of trade missions in several Eastern European countries, the assumption of diplomatic relations with Israel, and lastly, the ‘Peace Memorandum’ of March 1966, which highlighted opportunities for rapprochement with the countries of Eastern Europe without sacrificing the objective of reunification.

In the field of domestic policy, successes included further privatisations of federally owned businesses, the expansion of opportunities for wealth formation by employees through savings and share-ownership arrangements, and fresh ideas for the pursuit of educational and research policies at the federal level. The Federal Republic also took culturally important steps of self-reflection by holding prominent trials of Nazi war criminals and conducting a related discussion about the length of time during which legal redress could be sought for the associated crimes. During Erhard’s term, there were important preliminary discussions on reforming the laws governing public finances and emergency powers, on adopting the future Act to Promote Stability and Growth (Stabilitätsgesetz), on reforming the welfare state, and on fashioning a more flexible Ostpolitik; these were, in part, incorporated into the policies of the grand coalition that succeeded the Erhard administration. Those policies were not always in alignment with Erhard’s own convictions. In particular, the Act to Promote Stability and Growth, which passed into law in 1967, represented a striking and enduring departure from Erhard’s approach, given its aim of controlling macro-economic developments. After he was forced to resign as chancellor and party chairman, Erhard continued to be active in politics and the media as honorary chairman of the CDU, as a member of the Bundestag where, from 1972 onward, he was president by seniority, and as the founder of the Ludwig Erhard Foundation.

Myth and Criticism

In 2018, an impressive permanent exhibition dealing with the life, work and legacy of Ludwig Erhard was opened in his home town of Fürth. To a greater extent than almost any other politician of the Federal Republic, he became a legend during his own lifetime. With his round face, sonorous Franconian accent, optimistic temperament, and his almost ever-present cigar, he has remained a popular icon of West German economic success to the present day. Economic policy makers from across the political spectrum invoke his name and present themselves as his intellectual heirs. Since the beginning of his political career, however, Erhard has also been subjected to a great deal of criticism that still reverberates today. There has been debate over his role during the Nazi period, for example, although a careful and thorough biography that would bring to light and link up all the relevant sources in a knowledgeable fashion is still lacking. The originality and soundness of his thought has also been called into question, and he has been accused of having a deficient style of leadership. From time to time, market sceptics have also cast doubt on the fundamental importance of the regulatory decisions for which Erhard bore responsibility. To explain the economic upturn of the post-war years, they have instead pointed to the need for reconstruction (this view being known as the ‘reconstruction thesis’) or to the aid from the Marshall Plan.

That Erhard was ill-suited to the business of politics is probably the most valid of all these criticisms. Power bored him; it meant nothing to him. He was cut from much softer cloth than Adenauer and had no talent at all for political intrigues. Inspired by a political mission that he pursued quite candidly, he sometimes blundered when having to make compromises. He was an educator who wore the mantle of a politician but was always at odds with the mechanisms and motivating forces of party competition and organised interest groups. As chancellor, he relied on discussion within the cabinet, and he permitted himself to be outvoted without threatening to invoke his executive authority. A political style that was sceptical of power made him effective and influential as a minister of economic affairs, but it was no help to him as chancellor in the shark tank of Bonn. He did not cultivate or use party-political instruments of power. One case in point was the ongoing speculation over his membership of the CDU. Presumably, given the absence of a formal membership application it was simply tacitly assumed that he was in fact a member, in consideration of the erstwhile practices of the CDU as a poorly organised party of notables.

Advocate of a Liberal Social Order

In many accounts of the intellectual history of the social market economy, Ludwig Erhard’s own contribution appears strangely faint compared with that of renowned theorists such as Walter Eucken, Franz Böhm, Alfred Müller-Armack and Wilhelm Röpke. Yet he was more receptive to the advice of intellectuals than any other chancellor, and he counted sceptically-minded and independent spirits among his counsellors. Nevertheless, Erhard was definitely his own man and not merely someone who carried out the ideas of others. What distinguished Erhard from predominantly theoretical political economists was his understanding of the market from the viewpoints of business management and the consumer, as well as his desire for a practicable approach to policy that, while keeping to its objectives, would be flexible and durable in everyday decision-making – for example, in the form of a proactive and finely tuned policy of economic stimulus or stabilisation.

Erhard did not invent the term ‘social market economy’, but he did adopt it as a slogan for his policies. It did not refer, in his understanding, to an amalgamation of mutually incompatible principles of social and economic organisation. For Erhard, expanding the concept of the market economy by adding the ‘social’ component did not imply weakening the importance of the market by subjecting it to a supposedly higher morality associated with ‘social justice’; it rather signified a structurally coherent social order devoted to freedom and extending far beyond the market. Whereas a planned economy and economic interventionism turn citizens into subjects and supplicants, a social order based on freedom assures them not just prosperity, but also dignity, maturity and the opportunity for self-fulfilment. The most apt condensation of his thought can perhaps be found in a peripheral passage of the Düsseldorf Principles of 1949, in the formulation of which Franz Etzel played a leading role: ‘The “social market economy” is that order which assures that production is aligned with the true desires of consumers and that overall demand is met at the lowest cost, with the least exercise of political and social power’.

Erhard made up for his deficiencies in the exercise of power with the ‘power of a message’ (Klaus Hildebrand). It was precisely because he was neither ‘only an academic’ nor ‘only a politician’, but instead pursued a practical approach underpinned by theory, that his influence extended beyond limits of his times. An unseasonable and in many respects solitary reformer, Erhard rose from modest and precarious beginnings to achieve a historical stature that, could best be compared, in German history, with that of Freiherr vom Stein or Wilhelm von Humboldt.

The original german text was translated into English by Richard Toovey.

Curriculum vitae

- 1913–1916 Commercial apprenticeship

- 1916–1918 Active military service

- 1919–1925 Business and economics studies in Nuremberg, Erlangen and Frankfurt am Main

- 1925 Doctorate in Frankfurt am Main under the supervision of Franz Oppenheimer

- 1929–1942 Research assistant, junior manager and then deputy director of the Institute for Economic Observation of the Finished Goods Industry in Nuremberg

- 1942–1945 Director of the Institute for Industrial Research

- 1945–1946 Bavarian Minister of Trade and Industry

- 1947–1948 Director of the Special Office for Money and Credit

- 1947–1977 Honorary professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

- 1948–1949 Director of Economic Affairs for the unified economic area of the American and British zones of occupation (Bizone)

- 1949–1977 Member of the Bundestag

- 1949–1963 Federal Minister of Economic Affairs

- 1957–1963 Vice-Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1963–1966 Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1966–1967 National chairman of the CDU

- 1967–1977 Honorary chairman of the CDU

Literature

- Geppert, Dominik/Schwarz, Hans-Peter (Hg.): Konrad Adenauer, Ludwig Erhard und die Soziale Marktwirtschaft. Bearbeitet von Holger Löttel. Paderborn u.a. 2019.

- Hentschel, Volker: Ludwig Erhard. Ein Politikerleben. München 1996.

- Hohmann, Karl (Hg.): Ludwig Erhard: Gedanken aus fünf Jahrzehnten. Reden und Schriften. Düsseldorf u.a. 1988.

- Koerfer, Daniel: Kampf ums Kanzleramt. Erhard und Adenauer. Stuttgart 1987.

- Laitenberger, Volkhard: Ludwig Erhard. Der Nationalökonom als Politiker. Göttingen u.a. 1986.

- Löffler, Bernard: Soziale Marktwirtschaft und administrative Praxis. Das Bundeswirtschaftsministerium unter Ludwig Erhard. Wiesbaden 2002.

- Ludwig Erhard Zentrum (Hg.): Ludwig Erhard: der Weg zu Freiheit, sozialer Marktwirtschaft, Wohlstand für alle. Bielefeld 2018 [Ausstellungkatalog].

- Mierzejewski, Alfred C.: Ludwig Erhard. Der Wegbereiter der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft. Berlin 2005.

- Wünsche, Horst Friedrich: Ludwig Erhards Soziale Marktwirtschaft. Wissenschaftliche Grundlagen und politische Fehldeutungen. Reinbek/München 2015.