Issue: 4/2017

“Work for me, and I shall pray for you.” This was the headline of an article in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit about Islam in Senegal, published in 1985. The subheading of the article by Hille van Eist read “Even the president is powerless against the influence of the religious brotherhoods”, referring to Abdou Diouf, the second Senegalese president to take office since the West African country gained independence from France in 1960. Senegalese Islam is traditionally associated with brotherhoods, i. e. Islamic communities of faith, which are aware of their power and exert influence over the political class. Today, more than three decades later, the political, economic and social influences of the brotherhoods in Senegal are undisputed and their presence throughout the country is a clear indication of the deeply-rooted acceptance of their role within the population.

In all Senegalese cities, signs of the public presence of Islamic brotherhoods are discernible. In the capital Dakar, the streets are filled with colourful minibuses, so-called cars rapides, with religious inscriptions, which characterise the cityscape. In cities such as Mbour, Thies, St. Louis, Kolda and Kedougou, one encounters street vendors sporting portraits of caliphs, high-ranking Muslim clerics, on their necklaces, and taxis displaying pictures of saints venerated by the brotherhoods on their windscreens or number plates. In the inner-city districts, one cannot help but notice groups of young men who wear long colourful robes and are accompanied by vans blaring out suras of the Quran and religious songs. These are the Baye Fall, who collect alms to fund the organisation of religious rallies of the Mourides, a brotherhood founded in Senegal – one of its most important. More recently, pictures of Senegalese caliphs have also been appearing in graffiti form on bridges, the walls of houses and freestanding walls.

The obvious religious – predominantly Islamic – devotional imagery in public spaces may seem surprising, particularly as Senegal has a decades-long tradition of secularism. But as indicated by findings of the U.S. research institute PEW, published in December 2015, religion plays a key role for Senegalese people. 97 per cent of the Senegalese respondents in the representative PEW survey said religion was very important in their lives. This places Senegal second in the PEW ranking, directly behind Ethiopia, followed by Indonesia, Uganda and Pakistan. Atheists and agnostics are regarded with particular bewilderment. The extent of religiosity among the Senegalese has also been documented in a study by the Timbuktu Institute published in the autumn of 2016. According to its findings, the majority of the Senegalese respondents ages 18 to 35 are more familiar with the history of ideas relating to sharia than to secularism.

The key results of the Timbuktu study are significant as they affirm that religious authorities are held in higher esteem than state institutions by Senegal’s younger population. To many respondents, the imam, acting as the religious leader of a community, has greater credibility than representatives of state institutions. The study also documented the popular view among respondents that it is, in fact, the state that drives young people towards radicalisation as its representatives engage in corrupt practices and fail to take effective action to reduce unemployment and poverty. In its conclusion, the study states that Senegal’s young population are distancing themselves increasingly from the state and turning towards religious movements. The brotherhoods play a crucial role in this. Nearly 90 per cent of Senegalese consider them the proper representatives of Islam, according to the study. It is therefore hardly surprising that Macky Sall, who has been president since 2012, makes a point of stressing the role of religion and eulogising the religious authorities. For example in the following statement made in June 2017: “The state cannot function without religion.”

Secularism under Pressure?

How secular can a state still be whose first citizen highlights, and even politicises, the role of religion in this fashion? How can one explain the strong influence of religions on Senegalese society as well as the country’s political and economic development? And what are the distinguishable characteristics of Senegalese Islam and its successful coexistence with the democratic development of the West African country? These are questions this article seeks to address by describing Senegal’s idiosyncrasies and the most essential underlying component of its community spirit – religion. The discussion will focus mainly on Islam rather than on the influence of Christian churches in Senegal.

Aside from ethnic and linguistic diversity – seven national languages are spoken and French serves as the official language – there is also religious diversity in the country. At least 90 per cent of the 14.5 million Senegalese are Sunni Muslims, but there are also a few Shiite communities in Senegal due to a large Lebanese diaspora. Officially, between five and seven per cent of the population are Christian, mostly Catholic. A further one to three per cent are followers of traditional African (nature) religions. These are established particularly firmly in the Casamance region and emphasise strong links with nature, frequently recognising local kings as spiritual leaders.

Senegal is a good example of practiced religious tolerance. Both Muslim and Christian religious holidays are public holidays and representatives of the two religious communities visit each other for important religious celebrations, such as Christmas and Tabaski, the Muslim Feast of the Sacrifice. While interfaith marriages did not cause much of a stir in the past, there have lately been an increasing number of reports about plans for such marriages encountering problems. According to Islamic doctrine, Muslim men may marry Christian women, but a Christian bridegroom would have to convert to Islam before he would be allowed to marry a Muslim woman. In the past, this rule, which is generally adhered to in nearly all Muslim countries in the world, was not taken very seriously in Senegal. But an increasing number of men are now being persuaded to convert before marrying a Muslim woman.

Senegalese Islam is generally viewed as being liberal, but external influences have furthered the proliferation of a more orthodox Islamic doctrine. As polygamy in accordance with Islamic law is permitted in Senegal and Muslim men can marry up to four women, men who publicly oppose polygamy are finding themselves increasingly ostracised in certain circles. And while not all Muslim women in the capital Dakar wear a headscarf, the number of young girls who are only allowed out with their head covered is rising significantly in rural areas. At the same time, many Muslims struggle with the adherence to some of the religious rules. Although fasting during Ramadan, for instance, one of the five pillars of Islam, is obligatory for every Muslim, there are many Muslims in Senegal who do not adhere to the fasting regime. But these Muslims are increasingly coming under pressure from conservative groups and certain imams and are pilloried as not being proper Muslims. They are stigmatised in their immediate environment and can experience social exclusion.

Democracy and Islam – Lived Reality in Senegal

The Senegalese are proud of their democratic tradition of openness. The first post-independence president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, a Catholic, was elected in a predominantly Muslim country and governed Senegal for twenty years until 1980. Senghor is still held in high regard today. His election was linked directly to the goodwill of the Senegalese brotherhoods, which never advocated the introduction of a theocracy in Senegal, but always accepted secular law. The poet president, as he is frequently referred to, deliberately sought proximity to the influential brotherhoods and frequently stayed in rural areas – knowing full well that elections were decided away from the political elite in Dakar. While his successor in the role of president, the technocrat Abdou Diouf mentioned earlier, tended to keep his distance from the brotherhoods until the end of his term in 2000, they became more influential as rarely before under his successor Abdoulaye Wade (2000 to 2012). Wade, who was referred to as président talibé, made a point of appearing in public in a boubou, the traditional garment, and made a show of his allegiance to the Mouride brotherhood. During his time in office, marabouts received diplomatic passports to facilitate their travelling, were exempted from paying taxes and allowed to purchase land rights at greatly reduced prices.

His successor Macky Sall, Senegal’s fourth president, who has been in office since 2012, announced before his election that he would see to it that marabouts would become “normal citizens” under his presidency. It seems that this promise no longer holds. As his predecessor did before him, Macky Sall seeks proximity to the brotherhoods and has even introduced a special project for the modernisation of religious buildings with state funds as part of the Senegalese development plan (Plan Sénégal Émergant, PSE), which he initiated in 2015. Since then, several million euros of state money have been spent renovating or building churches, but especially mosques, throughout the country. This has secured him the goodwill of the marabouts. In September 2017, the appointment of the president’s brother, Aliou Sall, as chief executive of the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, a high administrative position dealing with the government’s tax income, elicited considerable political debate. Ever since, there has been speculation about the role of Thierno Madani Tall in this connection; he is an influential marabout who is well-known throughout the country and said to be the president’s personal marabout. Critics maintained it was no coincidence that Tall pointed out that “true charity begins in the family”, while preaching at Dakar’s largest mosque just before Aliou Sall’s appointment.

The first article of Senegal’s constitution makes very clear: “Senegal shall be a secular, democratic and social Republic. It shall ensure the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race, sex or religion. It shall respect all beliefs.” This clear statement, closely modelled on the French constitution and to be understood accordingly, also accounts for the fact that political parties with religious affiliations are prohibited in Senegal and that no parties may be founded along religious or ethnic lines. In keeping with the idea of religious equidistance, the state and its institutions should therefore keep their distance from all religions and not interfere in religious affairs. But the reality is somewhat different: The degree to which the principles of secularism are applied may vary in different countries and does not go as far in most countries as it does in France, where no religious symbols are permitted in public institutions. But the commingling of state and religious activities, mutual dependencies and mutual legitimisation of state and religious authorities in Senegal make it increasingly pressing to question whether the Senegalese state is, in fact, fulfilling the spirit of Article 1 of its constitution. In a secular system, the state does not fund churches and mosques. Secularism, the separation between state and religion, which was established in France based on anticlerical rather than fundamentally anti-religious grounds, is currently not practiced consistently in Senegal. The influence of the brotherhoods on the country’s political class is so strong that political figures only have limited prospects of success without their backing. We shall now examine ways in which politics and Islam consolidate each other’s power.

Arabic on the Advance as a Language Spoken in West Africa

The widespread geographic presence of Islam from West Africa to South East Asia also explains its cultural and linguistic heterogeneity. Arabic, the holy language of Islam, is now on the advance on the African continent as well. One trend that can be observed throughout Senegal is the expansion of Arabic-speaking Koranic schools as well as Franco-Arabic schools. 28 per cent of respondents in the above-mentioned Timbuktu study believe it would be sufficient for their children to be educated exclusively in a Koranic school.

Almost 90 per cent advocate for a combination of state school (based on the French curriculum) and Koranic school. Increasing numbers of parents are sending their children to the Franco-Arabic schools the state began setting up in 2002. There, the children are taught Arabic in addition to the subject-based content taught in French. Currently, the Arabic language skills are still mainly limited to memorising suras of the Quran and rarely reach a level required for good communication. Many observers believe in a few years an Arabic-speaking elite will hold the most important positions in politics, business and academia in Senegal. Some fear these individuals may in the long term decide to abandon French as the official language and incidentally adopt the social model predominant in most Arab countries – partly to mark a symbolic break with the language and the customs of the former colonial power. Subliminally, this debate also reflects the concerns of some that the Sufi interpretation of Islam, which is considered liberal, may be replaced by the Arab social model in Senegal and that the country may in time come to subscribe to a more orthodox religious interpretation. Prime Minister Mohamed Ben Abdallah Dionne, who was re-elected in August 2017, has repeatedly stressed the importance of the Arabic language for Senegal and announced an expansion of Arabic courses at all state universities.

Brotherhoods Determine the Nature of Islam in Senegal

A particular feature of Senegalese Islam is the fact that it is constituted by four distinctive Sufi brotherhoods. These faith communities “represent more of an identifying parameter than ethnicity and level of education in Senegal” and have a clear hierarchical structure. Each brotherhood is headed by a caliph-general as the religious leader. He is followed by his spokesmen and various dignitaries venerated as saints at a local level, who are referred to as marabouts or sheikhs. The marabouts rely on donations from their followers and alms collected by their religious students, the talibés, and act as religious authorities in society. Their advice is sought ahead of decisions in professional or private matters, they act as arbiters in disputes and they are viewed as agents imparting religious knowledge and local traditions. There are several caliphs and thousands of marabouts in Senegal. Many Muslims outside the country criticise these vast numbers of religious authority figures as Islam (with the exception of the Shiites) does not in principle have a clergy or clerical hierarchy.

In the past, the brotherhoods exerted their political power at election time by making recommendations in favour of specific candidates to their supporters. For decades, the system of ndigël (command in Wolof) caused political figures to compete for the benevolence of the caliphs and marabouts. This state of mutual dependence between public and religious representatives can be viewed as a special Senegalese social contract. The religious recommendations of the most important caliphs were instrumental in the election victories of most presidential candidates. Some changes have been noticeable in this area since the 1990s. Since that time, the brotherhoods have no longer relied solely on election recommendations in favour of candidates who had close links to them, but have increasingly turned into political actors themselves, putting forward candidates of their own for political mandates during elections.

Sufism represents a special movement within Islam that is characterised by ascetic, spiritual and mystical elements. A Sufi searches for the deeper meaning of the Quran and seeks to achieve the greatest possible proximity to God through hours of daily meditation, the so-called dhikr, dance and ecstasy. The personal and direct relationship to God is at the centre of all of a Sufi’s actions, which means they put their own desires second and dedicate themselves to leading a life that is pleasing to God. Love – including love towards others – plays a central role, which explains the fundamentally pacifist stance of Sufi Muslims. Brotherhoods practice the veneration of saints and celebrate the tradition of their sheikhs, who, according to Sufi belief, have a direct family connection to the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Besides the spiritual component, brotherhoods form a close-knit social network that includes mutual (financial) assistance and can represent a social control and security network. As follows are Senegal’s four major brotherhoods.

The Oldest

The oldest of the brotherhoods active in Senegal is also worldwide the most strongly represented one. It has followers not only in West and North Africa but also in the Balkans and in South East Asia. The Quadiriyya brotherhood was founded in the eleventh century in Baghdad, where its headquarters remain to this day. It became established in Senegal via Arabic-speaking traders – mainly from Mauretania. Its following is concentrated in the north of the country, in the area around St. Louis, the former capital of French West Africa. Some ten per cent of Senegalese Muslims are followers of this brotherhood.

The Smallest

The followers of the Layene represent the smallest brotherhood in Senegal. It was founded in 1884 by the fisherman Libasse Thiaw, better known to his followers as Seydina Limamou Laye, as an “imam by the grace of God”. The followers of this brotherhood venerate Libasse Thiaw as the reincarnation of the prophet Mohammad. They believe he appeared as the Mahdi, the reborn prophet, to lead Muslims towards ultimate salvation. His son is venerated as the reborn Jesus Christ, which is why the Layene celebrate Christmas as an important religious feast and include bible stories in their religious practices in addition to the Quran. Because of the syncretic character of this brotherhood its followers appear to be heretics, at least in the eyes of many Muslims from other countries. Most of them are found among the Lebou ethnic group in the capital Dakar.

The Largest

The largest of the four major brotherhoods are the Tijaniyyah. It accounts for around 50 per cent of the country’s Sunni Muslims. Its origins go back to 1780 in Algeria, where it was founded by Sidi Ahmed Al-Tijani and from where it subsequently spread throughout West Africa. While the brotherhood initially took an anticolonial stance and was not averse to violence on occasion, it became a peaceful organisation under the leadership of the Senegalese El Hadj Malick Sy (1855 to 1922) and is still willing to engage in dialogue to the present day. The brotherhood’s followers come from virtually all countries of West Africa as well as from the Middle East and Indonesia. It is deemed to be the largest brotherhood in West Africa.

Aside from the Quran and the Sunna, the handed-down deeds and dictums of the Prophet Mohammad (570 to 632), the followers of the Tijaniyyah brotherhood focus on service to the community. They reject asceticism, but the recitation of certain religious formulae after the five standard daily prayers represents an important idiosyncrasy of this brotherhood. In Senegal, the brotherhood has several branches or “houses”, represented by different caliphs in different cities. The “house” of Sy is deemed the most important branch of the Tijaniyyah, as its representatives are seen as the legitimate heirs to the first Senegalese to head the brotherhood. After the death of the 91-year-old caliph-general Sheikh Ahmed Tidiane Sy “Al Makhtoum”, his brother, Abdoul Aziz Sy “Al Amine”, was appointed the new caliph-general and leader of the brotherhood in the spring of 2017. Since the unexpected death of “Al Amine” in September 2017, just six months after his brother’s death, the 85-year-old cousin Mbaye Sy Mansour has been heading the brotherhood as its seventh caliph. President Macky Sall, almost the entire cabinet as well as a delegation representing the King of Morocco travelled to Tivaouane, the family’s ancestral home, directly after the caliph’s death, thereby emphasising the family’s importance.

Several hundred thousand pilgrims travel to Tivaouane each year to celebrate the Prophet Mohammad’s birthday by reciting verses of the Quran and phrases to praise him. This spectacle, which the Tijani refer to as Gamou, represents one of the country’s most important religious festivals. Besides the Sy family in Tivaouane, the most significant family branches are the Tall and Niasse, the latter are based in Kaolack. One branch located in Medina Gounass is known to be particularly orthodox as it demands strict application of Islamic law. Men and women strictly lead separate lives and do not shake hands by way of greeting.

The Most Influential

Unequivocally, the most influential of the four brotherhoods is the Mouride brotherhood, founded by Sheikh Ahmadu Bamba in Senegal in 1883. Although only approximately 35 per cent of the country’s Muslims belong to this brotherhood, it is nevertheless one of the fundamental factors of power in the country due to its economic, political and social influences. In 1887, Bamba, who was born in Mbacké, founded his own “holy” city of Touba, which has enjoyed special status in Senegal ever since. At the centre of Mouride ideology is the glorification of labour and the belief that hard physical work will bring one closer to God. A well-known saying among Mourides is: “Work as if you were going to live forever, and pray as if you were going to die tomorrow.”

The Mourides’ caliph-general, since 2010 Sheikh El Mokthar Mbacké, is considered the country’s most influential public figure. Even the president kneels before him in public and willingly permits this image of absolute subordination to be disseminated by the media. The Mourides have always cooperated closely with state institutions; during the colonial era, the colonial rulers took advantage of the Mouride work ethic by employing them in their peanut cultivation enterprises. Today, followers of the Mouride brotherhood practically dominate the country’s entire private transportation system, running a large network of companies and even a chain of petrol stations, Touba Oil.

Senegal’s Islam – Sufism or Salafism?

Since the 1990s and especially since the turn of the millennium, Sufi movements around the world – also in Senegal – are coming under pressure from Salafist preachers. The Wahhabi royal house in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have been increasing their presence in numerous predominantly Muslim African countries since the 2000s, particularly through the construction of mosques and Koranic schools and by providing scholarships. Iran has also increased its presence in Senegal although only 30,000 to 50,000 of the 14.5 million Senegalese are believed to be Shiites. The Al-Mustafa International University in Dakar, which is funded by Iran, awards 150 scholarships to young Senegalese each year, in the hope that this will strengthen the Shia and Iran’s influence in Senegal.

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have been intensifying their financial engagement in Senegal for years. The Islamic Development Bank, over which Saudi-Arabia has a significant influence, supports numerous infrastructure projects in Senegal and had invested around 200 billion U.S. dollars in the country by 2016. At the same time, Saudi banks promote bank accounts conforming to Islamic principles in Senegal; as half of all Senegalese do not yet have a bank account, the Senegalese market is deemed to be particularly attractive in the medium term.

Associations from Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf states also award several hundred scholarships to Senegalese every year. The Islamic Preaching Association for Youth (APIJ), which was founded in 1986 by university students returning to Senegal from Saudi Arabia, is financed by Saudi Arabia and now runs over 200 mosques all over Senegal. The association was officially recognised by the state in 1999 and is deemed to have a Salafist orientation. Wahhabi literature is distributed at APIJ mosques and Salafist ideology is preached. In addition to mosques and Koranic schools, ultraorthodox preachers who follow a Salafist ideology and try to attract followers in other Senegalese mosques are also frequently funded. It therefore comes as no surprise that many Senegalese joined internationally operating terrorist organisations such as the so-called Islamic State (IS), Boko Haram or “Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb” in the past.

Fundamentally, the increasing trend of Iran and other Gulf states investing in Muslim-dominated countries of West Africa is to achieve ideological supremacy and a monopoly on the interpretation of Islam practiced in the region. While the Twelver Shia that is practiced as the state religion in Iran does not have many followers in Senegal, the Wahhabi-inspired interpretation of the Islam of Saudi-Arabia reflects an ultraorthodox world view that claims to be based on the origins of Islam and rejects any deviation from this original Salafist era as forbidden innovation. Neither social model corresponds to the tolerant interpretation of Islam that has been followed for decades in the Senegal of today, which in many places is a syncretic interpretation including elements of local African religions. However, as the majority of the Senegalese population are Sunni, Sunni preachers with a Wahhabi or Salafist bent are making an effort to promote their ideology and stigmatise the Islam prevailing in Senegal as corrupted by the colonial powers and as inauthentic.

Salafism is the fastest growing Islamic movement of our time and highly heterogeneous. While the political and jihadist version of Salafism (so far) appears to have no particular relevance in Senegal, purist Salafist movements are clearly on the rise. Purist Salafists are non-militant and do not engage in an offensive strategy of immediate political transformation. However, they do follow the Salafist ideology that places God’s rule above the sovereignty of the people and categorically reject any secular laws that deviate from the fundamental principles of Sharia. The transitions from purist all the way to jihadist Salafism can be fluid, which probably explains why 15 imams have already been imprisoned for propagating Islamist content in Senegal.

Salafist preachers are increasingly putting the Sufi brotherhoods under pressure by denouncing their veneration of saints as well as their wearing devotional objects and the dhikr with its singing and dancing as “un-Islamic”. The Senegalese state is taking action and backs the Sufi brotherhoods. In 2016, an action plan against terrorism (Plan d´action contre le terrorisme, PACT) was adopted in collaboration with France, controls at the borders to neighbouring countries – particularly Mauretania and Mali – have been strengthened, and President Macky Sall proposed a ban on women wearing full body veils, the burka, by law because it was not in line with Senegalese culture.

The Senegalese government is aware of the risks and security challenges that international terrorism poses and has been holding the Dakar International Forum on Peace and Security in Africa every year since 2014. At this conference, high-ranking experts from politics, academia and the military discuss ways of how to deal with terrorist threats. Such measures indicate how nervous the Senegalese government is about potential terrorist threats nowadays. Senegal is still considered the anchor of stability in West Africa. The government has expressed its commitment to the Sufi brotherhoods which are acting peacefully, thereby underscoring the strength of its bond with the traditionally influential brotherhoods in the country. The brotherhoods for their part have positioned themselves unequivocally and repeatedly against the use of violence in the name of Islam and acknowledged their responsibility in the fight against violent Islamist groupings. For this reason, the “Islamic-African Forum for the Fight against Terrorism” was founded in March 2017, in which all the country’s most important brotherhoods are members.

Democracy or Maraboutcracy?

Senegal is a stable, democratic country in West Africa that has succeeded in establishing an impressive harmony between different ethnic groups and religions. The Sufi brotherhoods are making an important contribution to this. At the same time, the country is facing a number of challenges. International terrorism arrived in the region quite some time ago; poverty, a lack of prospects and corrupt elites are causing young Senegalese people to contemplate emigration and has made them become vulnerable to radicalisation as well.

The vitality of the Senegalese democracy was last demonstrated at the parliamentary elections on 30 July 2017. With a turnout of 54 per cent, the number of Senegalese making use of their civil right to vote was at its highest since almost 20 years ago. At the same time, the PUR (Party of Unity and Integration), which has some religious aspects to it, made fourth in the elections. The party stresses that it does not pursue any religious aims, but openly declares its support for the Moustarchidine movement that was founded in Iran in 1979 in the course of the Islamic revolution there. The party is still small and does not have a great deal of influence, but it is already showing confidence in doing well in the 2019 presidential election. It will be interesting to see how the party attempts to make an impact during the 13ᵗh parliamentary term.

The number of marabouts on the 47 lists for the parliamentary seats in the National Assembly during these last elections was larger than ever before in Senegal’s history since independence. This is a clear indication of the growing self-confidence of many of the brotherhoods’ representatives and, in the meantime, the willingness to shape politics has also been revealed by their political positions. Some of the marabouts were elected deputies and will do what they can to assert the interests of their brotherhoods even more directly in parliament in future. They will be assisted in their efforts by a number of newly founded Islamic associations and media portals.

The motivation and agenda of the marabout politicians can be very different from each other. But there is one constant: an unequivocal political will to further the interests of their respective brotherhood. They no longer rely on their indirect political and economic influence, but are turning into actors of the political process themselves. Mansour Sy Jamil for instance, an influential marabout of the Tijaniyyah brotherhood and party founder, tends to use populist anti-establishment rhetoric and focuses on championing the land rights of the followers of his brotherhood. Other marabout politicians, such as the three PUR deputies, demand the restoration of (Islamic) public ethics, oppose the consumption of alcohol and stress the value of the family in society.

Besides socio-economic and geopolitical challenges, the ideological dimension represents a further aspect on the list of possible threats to Senegal’s stability. The decades-long cooperation between politics and the brotherhoods, characterised by their mutual benefit, could lead to Senegal’s religious class developing into distinct entities. It is no longer only the demands of deference of political decision makers towards marabouts, the renovation of mosques and the maintenance of privileges that the brotherhoods have come to acquire. The marabouts are becoming political actors themselves, form political parties and associations, organise, and formulate political messages with religious overtones. The brotherhoods are challenging the country’s secular system – albeit without openly formulating the vision of the system to be based on Islamic law.

However, the greatest ideological challenges by far come from Islamist movements that threaten the state and repress the Sufi brotherhoods. The government under Macky Sall has made clear that it intends to take decisive action against Islamist protagonists. But the strong financial engagement of the Gulf states in the construction of mosques and Koranic schools as well as the granting of scholarships for university studies in Arabic-speaking countries is resulting in the emergence of an Arabic-speaking elite that could, in the long term, take an anti-Western stance in their ideology. To date, the brotherhoods are still believed to act as a buffer against the influence of Islamist groupings and guarantee the country’s stability. They can (still) be seen to play a positive role. They make a significant contribution to the peaceful understanding of Islam and to religious dialogue, and are the guarantor of social cohesion in Senegal.

With their syncretic and mystical outlook, the brotherhoods are more influential in Senegal than in any other West African country. This strong influence has advantages and disadvantages. The influence of the marabouts is of concern as they are increasingly engaging in political activities as religious representatives, which will in the long term undermine the country’s secular system. That said, the success of the democratisation process in Senegal over the last few decades has been in part due to the fact that the peaceful Sufi brotherhoods resolutely supported the state – of course also to benefit from state privileges.

In a world of multidimensional challenges, reliable partners are definitely important, and as the brotherhoods have the necessary authority to help curb Islamist ideologies, it will be prudent to closely follow their future engagement and not condemn them prematurely. With its democratic culture, Senegal is a role model for West Africa. The alliance with the peaceful brotherhoods has so far proved successful in the battle against destabilising factors. The preservation of freedom and security can only be guaranteed by democracy, and not by the rule of religious figures, maraboutcracy.

-----

Thomas Volk is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s office in Senegal.

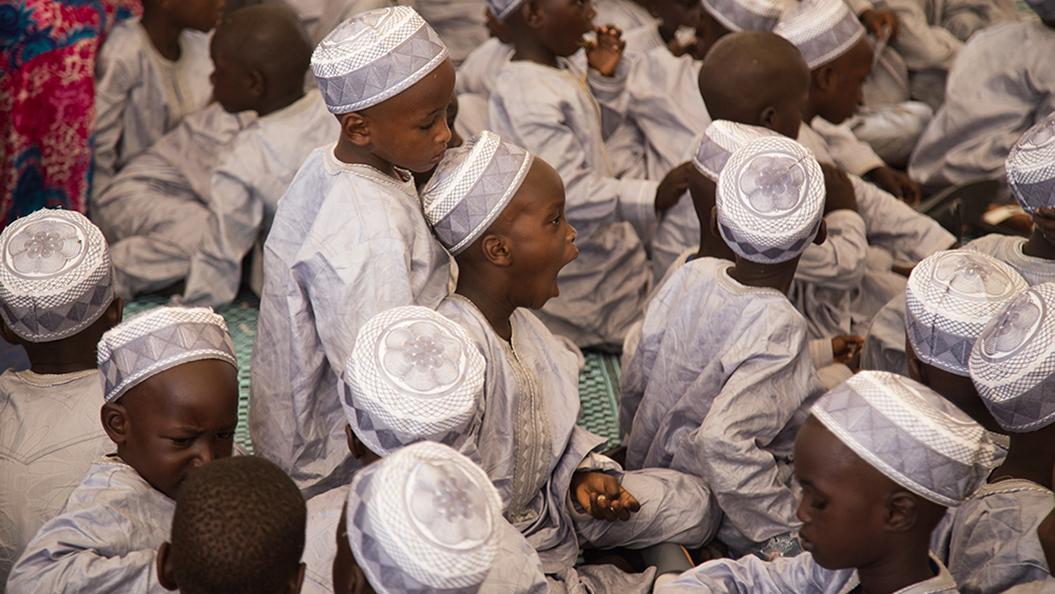

The images in this article are part of the report “In the Name of Koran” by photographer Sebastian Gil Miranda. They depict the every-day life of pupils in Islamic boarding schools, the daaras. The entire photo series is online at: http://www.sebastiangilmiranda.com/in-the-name-of-koran-talibes-in-senegal.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.