Issue: 4/2024

Dear Readers,

Hamas’ attack on Israel and its ramifications, as well as Russia’s war against Ukraine, have shaped foreign policy discussions in Germany in the last two years. There are reasons for this: the attack on Israel, in October 2023, hit a state for whose security our country quite rightly feels particularly responsible. In turn, Russia’s attack on Ukraine poses a direct threat to the security of Germany and Europe. Both states, Israel and Ukraine, are confronted with adversaries that threaten their very existence.

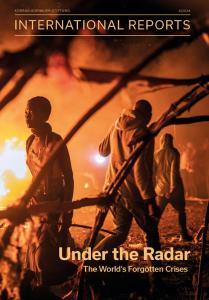

Nevertheless, it is important not to lose sight of other crises. Even conflicts that have flown under the radar for years can suddenly and unexpectedly escalate again or take new turns, as the recent example of Syria has clearly shown. “Crises don’t just go away,” says Afghanistan expert Ellinor Zeino in this issue of International Reports. In fact, they are numerous and multifaceted. This starts with internal conflicts, which often become enormously complex due to the interference of external parties. One example of this is the conflict in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which Jakob Kerstan analyses in his article. The spectrum continues with the threat posed by terrorists and with homegrown humanitarian crises, as outlined by Maximilian Strobel with regard to Cuba. And it extends to the security-related impact of climate change. Frederick Kliem and Timm Anton elaborate on this in their text on South Asia.

The question of how Germany, jointly with its partners, can effectively defend its interests in international crises in future therefore remains on the agenda. One institutional expression of this insight is the Study Commission set up by the German parliament in summer 2022 with the task of drawing lessons for future German participation in international crisis missions from the 20-year deployment in Afghanistan. The Commission’s final report is still pending. However, it is clear that considerable efforts are needed in Germany to bridge the disparity between our goals and the resources available – one could also say: the glaring gap between the aspirations and reality of German foreign policy.

These resources include the clout of the German armed forces, the Bundeswehr, and the strength of the German economy. While some progress has been made since 2022 in terms of the Bundeswehr’s operational readiness, this is nowhere near enough; especially as NATO’s two per cent target, which has only been achieved sporadically to date, is likely to be obsolete with Donald Trump returning to the White House. And the economy? Pessimism currently prevails there. Yet, without a modern Bundeswehr and a strong economy, German foreign policy lacks important levers of influence. In many cases, it sees itself reduced to moral appeals and references to international law, which, however, is not capable of ending crises and wars on its own, as emphasised by Franziska Rinke and Philipp Bremer in their article.

In addition to these tangible resources, there has also been a lack of an intangible resource, namely the ability to think strategically. The symptoms: wishful thinking and an overemphasis on good intentions while neglecting the actual consequences of one’s own policies. To remedy this deficiency is as difficult as it is important. A sensible proposal in this context is the establishment of a National Security Council, as exists in many other countries. While such a body is by no means a panacea, it could be suitable for guaranteeing a holistic approach to our foreign policy.

In order to correct the imbalance between aspiration and reality described above, our objectives and standards also need to be readjusted. This should result in clear prioritisation and self-restraint on several levels. Firstly, this concerns the question of where we get involved. It is tempting to react to every crisis with the demand: Germany must do something about this! But the truth is: Germany alone, but also Europe or even the political West as a whole, do not have the strength or the will to intervene decisively in every crisis in the world.

For the foreseeable future, priority will be given to national and collective defence. Beyond this, the focus for Germany should be on its immediate European neighbourhood and securing important trade routes. Even here, Germany and Europe are currently reaching the limits of their military and political capacities. This is illustrated in the articles by Jakov Devčić and Daniel Braun on the Kosovo conflict and by Stephan Malerius on the various crises in the South Caucasus, as well as by Germany’s difficulties in providing the EU mission with the appropriate warships on a permanent basis in order to protect the trade route through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Meanwhile, there will always be crises and conflicts that rightly outrage us, but which do not directly affect our core interests. In their article, Moritz Fink and Saw Kyaw Zin Khay impressively describe the courageous struggle of many citizens against the military junta in Myanmar, which stole the 2020 election from them in a coup and has been waging war against its own people ever since. To be honest, however, Germany and the EU will not play a decisive role here.

Secondly, self-restraint is also required when it comes to the question of what goals we pursue once we decide to intervene in a particular crisis. It has long been clear that comprehensive state-building missions – Afghanistan being an extreme example – have largely failed. There is much to suggest that a limitation to clearly defined objectives that affect German and European core interests could be a good concept for future commitments.

One such objective is combating terrorism. Another is the avoidance of mass migration to Europe. In their article on the war in Sudan, Steffen Kruger, Gregory Meyer and Nils Wormer logically argue that Germany and Europe should pool their political and economic capital in an attempt to provide decent accommodation within the country or in the immediate neighbourhood for the approximately 13 million Sudanese who have been forced to leave their homes due to the conflict.

Thirdly, we should also lower our expectations when choosing counterparts who are able to exert a lasting influence on the development of crises on the ground. Only in the rarest of cases, these players will conform to our democratic and socio-political ideals, in some cases they will even be diametrically opposed to them. Nevertheless, we should at least seek dialogue where there may be overlapping interests on issues that are important to us.

And our values? These will continue to form the basis and orientation for our future actions. And we can certainly be self-confident in that respect. The German political foundations, for instance, advocate democracy, human rights and rule of law worldwide, and work together with parties and parliaments in a large number of countries. However, German and Western policies must take account of the respective historical and social context. For even if it is undoubtedly a good thing that women in Afghanistan, for example, have had better prospects and more rights for two decades, and that this experience may yet influence Afghanistan’s political future, we must first recognise this: it was not sustainable. The Taliban were back twenty years after their fall in 2001. The difference between then and now is that the West is more exhausted – both militarily and politically. This does not help anybody except the enemies of the liberal values we want to defend.

I hope you find this report a stimulating read.

Yours,

Dr Gerhard Wahlers is Editor of International Reports, Deputy Secretary General and Head of the Department European and International Cooperation of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (gerhard.wahlers@kas.de).