Issue: 3/2021

Over the last few years, right across the globe, journalism has been in crisis on numerous fronts. The sector is struggling with an economic crisis due to changes in the media market and with a technological crisis caused by the direct impact of the digital revolution on the production and dissemination of information. However, the impact that these structural transformations have on journalism varies according to the particular context, as different journalistic cultures also play a role in this respect. Since its emergence, the internet has accelerated information cycles so that we now have a constant stream of news that keeps us informed 24/7. During the coronavirus pandemic, this constant, globally networked stream of information coalesced with an issue that affected the whole world. This certainly facilitated access to high-quality information regardless of location, but it also revealed the limitations of journalism that is restricted to a national context.

This global exchange of information sheds new light on journalistic problems, such as disinformation, the threat to freedom of expression, and the influence of news outlets. These phenomena affect journalism worldwide, but they have a greater impact in countries such as Argentina – a country that lacks the legal, professional, ethical, and educational institutions that we are familiar with in the West. The same applies to the financial independence of the media. For a country like Argentina, which had been in crisis for decades, the global economic downturn caused by the pandemic has led to a 9.9 per cent drop in GDP, according to the World Bank. These difficulties come on top of the structural deficiencies in the health care system that led the government to impose a harsh lockdown of more than 100 days, which further exacerbated the economic crisis. In the second semester of 2020, 42 per cent of Argentina’s urban population were living in poverty. Extreme poverty affected 10.5 per cent of the population, while child poverty stood at 57.7 per cent. In the midst of this economic recession, most of Argentina’s media outlets survived thanks to income from government advertising. The situation is similar in other Latin American countries. For years now, the region has had to deal with the fact that incumbent governments are the main source of information and funding. The situation is particularly critical for local media outlets, which are almost totally dependent on the government for information and funding.

Lack of press freedom is one of the reasons behind the poor ranking given to democracies in the region. Recent setbacks led the Democracy Index 2020 to place Latin America on a par with Eastern Europe. Together, the two regions make up half of all countries with flawed democracies. These countries share common deficits, such as lack of transparency, poor access to public information, as well as tensions between government officials and the press – ranging from the absence of press conferences to explicit attacks on the media and journalists.

This article provides an overview of the situation regarding journalism in Argentina and highlights three factors that illustrate the particular conditions affecting journalism in Latin America: public distrust of the news, restrictions on press freedom, and how the profession has had to adapt to these conditions.

Distrust and Political Use of Disinformation

According to a study by the Reuters Institute, only one in three Argentines trusts the news disseminated by the media. The degree of trust in traditional media (33 per cent) is similar to trust in social media (28 per cent). However, according to the results of this survey, trust in the news in Argentina declined by ten percentage points between 2018 and 2020. During this same period, trust in the national media ranged between 39 per cent and 57 per cent. The percentage of respondents who consider themselves distrustful or neutral towards the media is similar to the percentage of those who say they trust the media.

In the 2019 presidential elections, Argentina consolidated a two-party system in which two competing party coalitions, Frente de Todos (centre-left) and Juntos por el Cambio (centre-right) garnered nine out of ten votes. This social polarisation is reflected in the media and in the attitudes of journalists – many openly disclose their political views, which affects the credibility of the news. The fact that no single medium attracts trust levels in excess of 50 per cent is indicative of a precarious relationship with journalism. In Argentina, no single medium is preferred by the majority of the population and hence is in a position to shape public opinion. The government exploits the public’s fragile relationship with information to openly denounce the media and journalists as perpetrators of lies and confusion. At the start of the pandemic, in March 2020, the Edelman Trust Barometer revealed that the media, journalists, and politicians were viewed as the least trusted sources of information. It was predictable that this situation would deteriorate further over the following months, especially in a country like Argentina, which has a poor record in the fight against COVID-19 (2,336.19 deaths and 108,846.63 infections per million inhabitants, as of 30 July 2021). According to the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, 59 per cent of respondents in the 28 countries surveyed (including Argentina) believe journalists spread false information. This percentage is roughly in line with the two-thirds of respondents who do not trust the news, according to the studies cited above.

The quality of information and its counterpart, disinformation, are also indicative of the conditions under which journalism is practised. An evaluation of disinformation indicators in 32 digital media channels in Argentina concluded that 21 of these media presented a high risk in terms of disinformation, ten presented a medium risk, and only one truly met information quality criteria. The lowest ranking was given to areas relating to operational and editorial integrity, such as transparency of ownership, financing, and handling comments and corrections. This result is also linked to the fact that Argentina’s media does not traditionally have institutions for dealing with issues of ethics and self-regulation – bodies that are needed for the establishment of common guidelines. Very few media outlets have codes of ethics or ombudsmen for their readers, and only one newspaper has joined global initiatives to promote quality standards in journalism, such as the Trust Project.

In this general climate of public distrust of the news media, during the pandemic, the national government under President Alberto Fernández (Frente de Todos) ramped up tensions with the press still further. In the name of fighting disinformation and fake news, government agencies promoted initiatives that stirred up controversy with journalists and the organisations that represent them. An official advertising campaign told citizens that they were living in an “infodemic”. “That’s why, if you need information, we ask you to consult official sources. Preventing the infodemic is another way of looking after each other” went the message, in this way discrediting other, non-governmental sources. Although Argentina’s civil society has two fact-checking organisations, the government officially supported two initiatives tasked with flagging up information about the coronavirus that the authorities viewed as fake news. We should mention here that Argentina has a public broadcasting system that is very different from its counterparts in Europe. The Argentinian system has no budgetary autonomy, and its governing bodies are politically appointed by the government in power. The state news agency Télam – from which one of the two afore-mentioned initiatives originated – is also not comparable to other publicly run news agencies, as it is under the control of the Secretariat of Media and Public Communications. Télam created Confiar, an internet platform tasked with fighting the “infodemic”, which the website describes as an “information epidemic within the pandemic”. Another initiative in this direction was the Defensoría del Público (strictly speaking, a government agency under the control of the supervisory body stipulated in the Audiovisual Media Law), which tracks the “symbolic violence and malicious information that has been previously broadcast”.

Professional associations, such as the Foro de Periodismo Argentino (FOPEA) and the Asociación de Entidades Periodísticas Argentinas (ADEPA), have expressed their concern about government authorities dictating what pandemic-related information is deemed appropriate. Indices, such as the Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index, view such measures, taken under the guise of a health crisis, as restriction of information and pressure on the press. Although Argentina’s ranking fell in this report, it is still categorised as a free country.

The low level of trust in the news identified by the surveys reflects a general climate of distrust. However, within this environment, people have a thoroughly pragmatic relationship with the media. Indeed, in the specific case of the coronavirus pandemic, international studies have shown that the public appreciated the role of the press, despite their general distrust of news organisations. A special study on misinformation about the coronavirus revealed that the majority of Argentines felt the media helped them to understand the crisis (67 per cent of respondents) as well as the countermeasures in place (75 per cent). These percentages were higher than in the UK, the US, Germany, Spain, and South Korea.

Press Freedom under Pressure

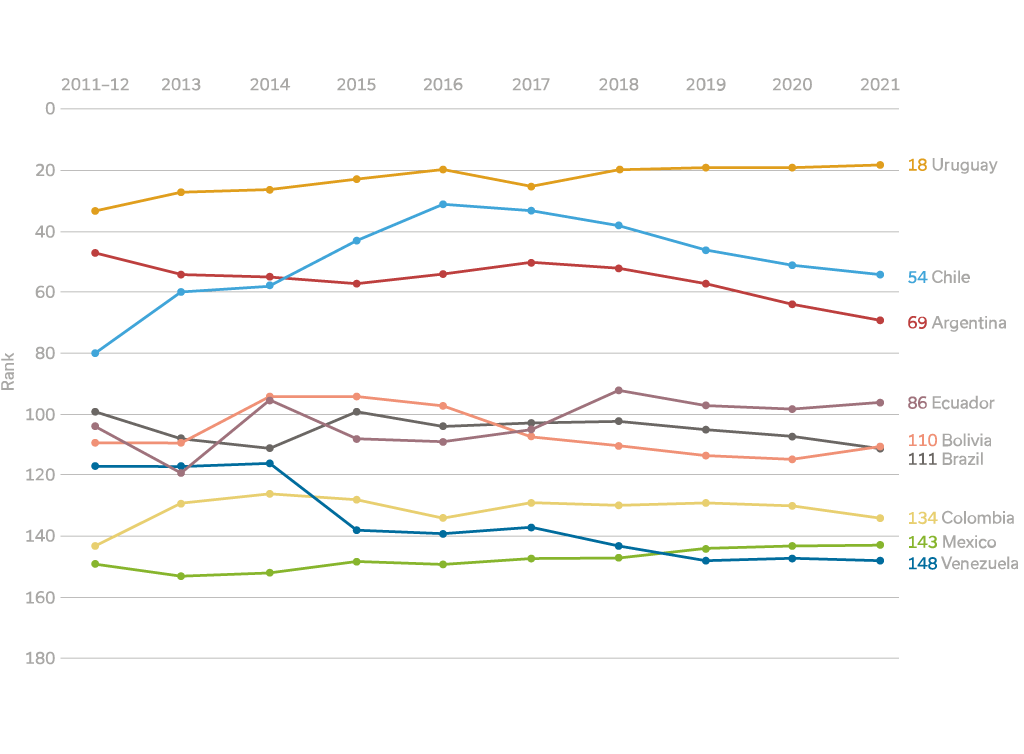

The public debate is affected by the problematic relationship between the government and the press. These tensions are also reflected in press freedom indices, such as the annual ranking published by Reporters Without Borders. This index is based both on direct attacks and structural factors such as pluralism in the media system, the legal framework, infrastructure, transparency, and censorship. Until 2019, Argentina was in the top third of the 180 countries assessed. Since then, only two South American countries have made it into the top third: Uruguay (18) and Chile (54). Argentina (69) is now in the middle of the table, along with Ecuador (96), Brazil (111), and Bolivia (110). At the bottom of the table are countries where journalists face a severe threat of violence, such as Colombia (134), Mexico (143), and Venezuela (148). Of the countries mentioned above, only Uruguay, Mexico, and Ecuador have recorded a slight improvement in journalistic freedom over the last five years, which points to a general deterioration in the Latin American region.

The aggressive behaviour of presidents towards the press is not unprecedented in the region. Heads of state, such as Rafael Correa (Ecuador, 2007 to 2017) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (Argentina, 2007 to 2015), regularly attacked journalists through official channels and their personal Twitter accounts. This antagonistic style is not limited to one side of the political spectrum but tends to be a typical feature of populists on both right and left. The deterioration of relations between Latin American presidents and the press was evident at the 2021 meeting of the Inter American Press Association, which explicitly mentioned heads of state who harassed journalists: “The political powers continue to discredit and stigmatize the practice of journalism – creating a hostile climate that may degenerate into concrete violent actions against the media and journalists. Presidents Nayib Bukele of El Salvador, Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, and Alberto Fernández of Argentina are the main harassers of journalism. Also, in Bolivia, Venezuela, Cuba, El Salvador and Nicaragua, governments use state-run media and social networks to discredit journalists.”

Fig. 1: Development of Freedom of the Press in Latin American Countries 2011–2021

Source: Own illustration based on Reporters Without Borders 2021: World Press Freedom Index 2011–2021, in: https://rsf.org/en/ranking [16 Apr 2021].

The same organisation also drew attention to the risk that governments could use this tension to restrict the legal space in which journalism operates. One example is the Argentine government’s proposal to enshrine in law the word “lawfare”. This legislative manoeuvre is intended to criminalise investigative journalism that is supposedly based on a conspiracy between journalists, politicians, and the judiciary. Professor Carmen Fontán defines the term “lawfare” as “the interplay between judges, media, and political and economic power with the intention of manipulating the application of the law to the disadvantage of certain political figures or political groups from the [editor’s note: leftist] national populist camp.” Argentina’s government also introduced a bill to the Mercosur Parliament that aimed to provide a legal framework for combating alleged “lawfare” throughout the region. The term is also frequently used in public by Rafael Correa and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner – alluding to the corruption trials in which they are involved and the media coverage of them, which they describe as part of a “war” that is being waged against them “by the justice system and communications media”.

This open harassment of journalists by government officials has been accompanied by an increase in direct attacks by protesters when the press attempts to cover a public event. After a decline over the last few years, 2020 saw a 40 per cent increase in attacks on journalists in Argentina, according to the Argentine Journalism Forum. However, the number is still far below the pre-2014 level.

Restricting Journalists’ Access to Information

The strained political and economic situation also complicates the issue of press funding, as governments are major advertising customers in the media market. Public advertising campaigns mean the Argentine government has become the number one advertising client of many media companies. One indicator of the need for alternative funding is the number of media outlets that have applied for the Global Journalism Emergency Relief Fund for local news, launched by the Google News Initiative in April 2020. In the first two weeks of the call for applications, it received 2,350 applications from 17 countries in Latin America. Of the 1,000 organisations selected for funding, 90 per cent were small, struggling operations with fewer than 26 local journalists. Government advertising, as the main source of funding for journalism, has a major influence on journalistic activity because governments provide both funding and official information. From this privileged position, they can restrict access to official documents or obstruct independent investigations.

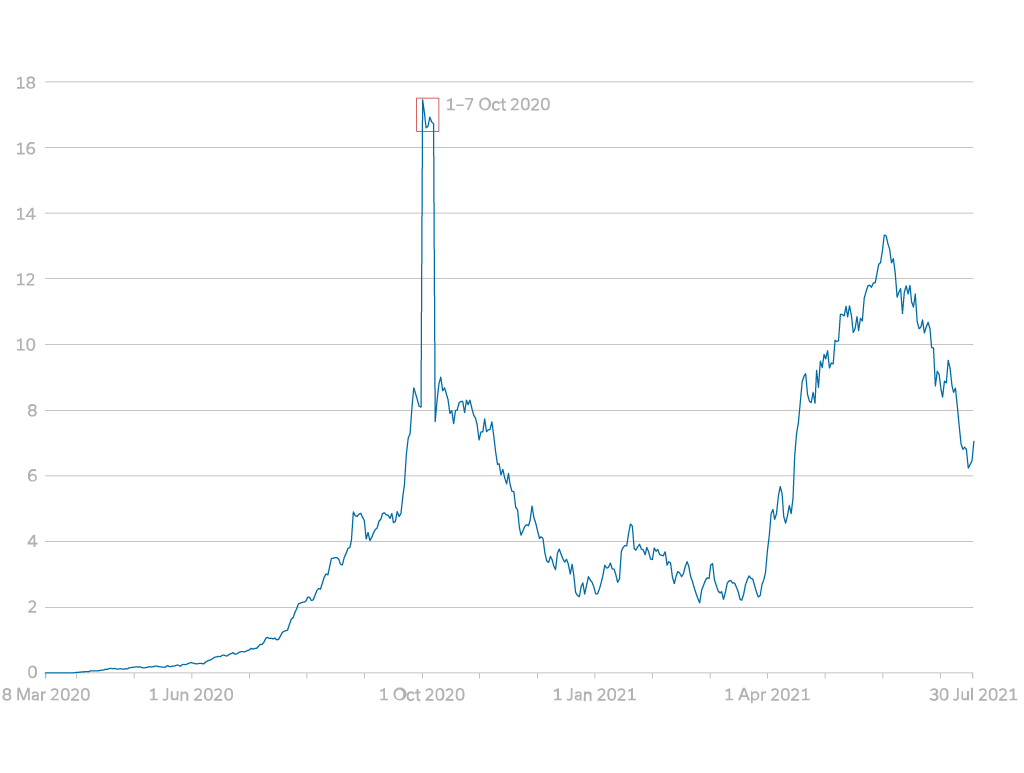

The difficulty of accessing public information is one of the main differences from journalistic practice in the West. Argentina only passed a law granting access to public information in 2017. It was supposed to end the longstanding political culture of secrecy and absence of public statistics; however, reports on the management of the pandemic reveal that problems still remain. Official websites only began publishing data about the public health system in July 2020. And information about the vaccination campaign was only published two months after its launch in December 2020 – and even then, the data was incomplete. Inconsistencies in the COVID-19 test registry led Oxford University’s Our World in Data website to exclude data from Argentina between September and December 2020. The graphs on the website also show a sudden jump in the number of deaths between 30 September and 7 October 2020, confirming that deaths had been inadequately recorded over the preceding months. As a result, the figures had to be readjusted over the following weeks.

Additionally, journalists were particularly affected by the general restrictions imposed as a result of the pandemic as they depend upon access to information and require the ability to move around freely, both at home and abroad. Journalism is considered an essential service in Argentina, so it is not subject to restrictions on movement, but the general restrictions on public transport that were imposed in the world’s eighth largest country have been particularly tough, at times involving the complete shutdown of services. According to Oxford University’s Response Stringency Index, Argentina is one of the countries that has imposed the most restrictions. The index looks at nine indicators, including school closures, workplace closures, and travel restrictions. On a scale of 0 to 100, with the higher values representing greater restrictions, Argentina was given a score of 100 in the weeks that immediately followed the declaration of a health emergency on 23 March 2020. On 3 November 2020, this still stood at 80, despite lockdown restrictions being eased. In some districts, the restrictions on citizens’ freedom of movement went so far that the national press were banned from entering and had to go to court to report on the existence of detention centres for suspected COVID-19 cases. It was thanks to social media posts by citizens and opposition parties that this situation was echoed in the press and by international organisations. This made it possible to escape prosecution, for example, by the government of the province of Formosa under its Peronist governor Gildo Insfrán. Insfrán has been continuously re-elected for the last three decades. This situation illustrates how provincial governments can abuse their power and prosecute anyone who voices criticism by claiming it is disinformation or hostile media coverage.

Fig. 2: COVID-19 Deaths in Argentina (per Million Inhabitants)

Source: Own illustration based on Our World in Data 2021: COVID-19 Data Explorer. Argentina, in: https://bit.ly/3klFric [30 Jul 2021].

Another issue that highlights the difficulties involved in accessing information is the absence of press conferences. This vital means of communication during a pandemic has been utilised only rarely in Argentina, and this has been the case for the last 20 years. Press conferences, as an opportunity to hold governments to account, have not yet gained a foothold in the country’s democratic culture. Since democracy was restored in 1983, Argentina has alternated between governments that hold press conferences fairly regularly and others that only use this instrument in exceptional cases or suspend it altogether. Ever since the social and political crisis that beset Argentina in 2001 and led to the installation of a transitional government until 2003, press conferences have only been held sporadically. National and local governments prefer to bypass the press and make their announcements via their own channels or social media. This method was introduced by Peronist president Néstor Kirchner (2003 to 2007). He also used it to openly attack journalists who attended presidential press conferences, and it was continued by his successor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007 to 2015). She maintained very few contacts with the press during her term as president, and since her appointment as vice president in 2019, these dwindled to virtually nil. Mauricio Macri (2015 to 2019), the first democratically elected president of a non-Peronist alliance this century, held more press conferences in one term than his predecessor held in two. However, they became less frequent towards the end of his term, falling from 26 conferences in 2016 to just seven in 2019. After taking office in December 2019, President Alberto Fernández initially chose to hold press conferences to make announcements about lockdown restrictions, but he later switched to recorded speeches and interviews with a few carefully selected media outlets. The press releases section of the government website states that President Fernández gave 15 press conferences and 95 exclusive interviews during his first 16 months in office. It is now common for events to be broadcast by official media, as was the case with the opening of parliament in 2020. Other press outlets are refused access, so journalists are limited to commenting on the images broadcast by the Office of the President.

Conclusion

Argentina provides a good example of certain conditions that are also prevalent in many other countries in the region. The press has operated under political and economic constraints for many years. Many media outlets are so dependent on government advertising that any reduction in their budgets can lead to job losses. For example, Buenos Aires alone has seven 24-hour news channels (Todo Noticias, La Nación Más, A24, Crónica, C5N, IP, Canal 26) on pay-TV. All these broadcasters compete directly with each other for advertising revenue. Some of them gain a competitive edge by giving sympathetic coverage to certain parties and trade unions. Analysts refer to this type of journalism as “militante” (committed) journalism, by which they mean an explicit political positioning, which is often linked to financial investments.

These limitations have shaped a journalistic culture that is more akin to an interpretive model than to journalism proper, which actually holds governments to account. The term interpretive model refers to a surfeit of opinion and analysis at the expense of an objective presentation of the facts. One symptom of this trend is the decline in investigative journalism that has been observed since the turn of the millennium. Since journalists often lack opportunities to control those in power, civil society has taken an active role in demanding transparency and access to public information. In doing so, it supports journalists in their research. This builds a strategic alliance between civil society and the media.

The restrictions on freedom of information in Argentina are different from the dangers faced by journalists in countries such as Mexico or the state persecution of the media that exists in Venezuela. Nevertheless, they have a negative impact on the practice of independent journalism. On the other hand, the global nature of information about the pandemic has rapidly transformed reporting, improved the transparency of official data, and attracted support from international organisations that support press freedom. Interaction with international media is also helping to raise standards in the Argentinian press.

– translated from German –

Olaf Jacob is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s office in Argentina.

Dr. Adriana Amado is a Researcher at the Universidad Argentina de la Empresa and President of the NGO Infociudadana.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.