Event reports

Answers to these complex questions were discussed during a session at the 3rd International Writers Festival in Jerusalem, hosted by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung on May 15, 2012. Focussing on the aftermath of the "Arab Spring" was of particular interest to the participants. From the very beginning of Writers Festival, KAS Israel has been one of the partners and has been eager to add a political perspective to the literary event. Michael Mertes, Director of the KAS Israel, remarked in his welcoming words on the the positive aspects of the Arab Spring, but also pointed out that there was no automatic mechanism for progress in history.

On the panel, writers from Europe and the Middle East continued in that direction, debating the latest developments in the Arab world. Participants included:

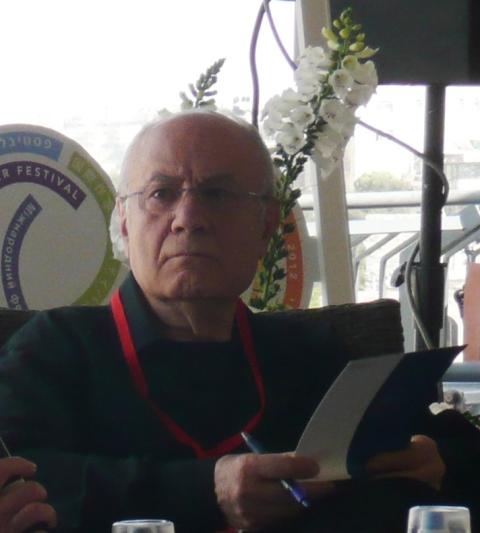

- Eli Amir, prominent Israeli writer, born in Iraq, speaks fluently Arabic and has many connections and a rich experience with regard to the Arab world;

- Boualem Sansal, Algerian writer now living in exile in France where he earned much criticism because of his comparison between the Arab dictatorships with the Nazi regime;

- Aleksandar Hemon, a young writer originally from Bosnia whos has been living in the United States sine 1992. From personal experience he is very much aware of tensions between the European and Muslim culture;

- Lukas Bärfuss, a Swiss author and playwriter, dealing with stories of people from conflict zones.

The participants of the symposium expressed different opinions on this issue, leading to a lively discussion. Eli Amir said that in Arab autocracies the income and social status of intellectuals was often linked closely to the ruling regime. In such countries experts needed to enter an employers' liability insurance association. As a matter of fact, it was not unlikely to lose one's occupation when publicly opposing the regime in power. As an example, Amir related the fate of Ali Salem, the successor of the famous Egyptian writer Naguib Mahpuz, who immediately lost his job when he pleaded for a dialogue with Israel.

Amir believes that a merger of several Arab intellectuals could have sent a strong signal to the ruling elite, and thus serving as protection shield against retaliation. He is convinced furthermore that the power of writing was enormous - the pen could turn into a weapon for the writer. In the end, no democratic political change could come about, if the intellectuals themselves were not committed to democratic values.

Boualem Sansal shared this opinion, arguing that intellectuals were often regarded as "traitors" because they did not want endanger their comfortable life by anti-government statements. Public criticism of the regime, be it only indirectly through art, turned the writer into a "public enemy" because he violated the established order. Sansal conceded that in political conflicts there was more than one truth. Nevertheless it was important that the intellectuals had the courage and strength to stand up for their beliefs. As long as a writer remained silent, he or she might become an accomplice of the dictatorship.

According to Sansal it was a universal human obligation to fight against injustice - not only to save one's own life, but also that of future generations. Civic courage was a key factor for improving the political situation, quoting the Algerian journalist and poet Tahar Djaout: "If you are silent, you will die; if you speak, you will also die, so speak and die." 48 hours later, Djaout was actually murdered.

Aleksandar Hemon, however, himself a refugee from Bosnia now residing in the United States, argued that moralizing from a safe country was easily done. Nevertheless, one could not ask the intellectuals in the Middle East to go in to the opposition and thus, possibly putting theirs lives in danger. In his view, it was the task of intellectuals to observe the events carefully and document them in books, movies or otherwise. The self-perception of a writer was to tell stories of individuals rather than reporting on the nation's political development.

Lukas Bärfuss opposed to take the writer's artistic freedom and to require him to refer to a political stance. Even silence could be interpreted as an intentional decision. As ab example, he cited the historical Swiss neutrality. Notwithstanding, fear was often the reason for silence. In this context, Bärfuss mentioned Heiner Müller's statement that there was such a thing as a human right to cowardice. Agreeing with the other participants to be required to oppose injustice, Bärfuss made it clear that this was actually the responsibility of every citizen, not only of the writer. First and foremost, a writer must be understood as an artist and not as a politician.

Eli Amir could not go along with that saying that a writer owed it to himself and to the next generation to fight for the right cause. As an example of a successful political engagement of writers he referred to the Zionist movement. In view of the developments in the Arab world, the revolution could only be successful if the educated and influential sections of the population were truly supportive. Amir demanded that Europe should not remain silent, because it was more than just a local upheaval, but a revolution of global importance. Values such as human dignity were at stake, and thus became a relevant topic for Europe, too. Europe was lacking a fundamental understanding of the Arab world. Political and social change could not be achieved within a short period through protests, as was often assumed, but must be actively and permanently supported from Europe.

Boualem Sansal was afraid the political vacuum created by the revolution would lead to a victory of the Islamists. Accordingly, the failure of the "Arab spring" meant that in the end the Islamists reaped the benefits of the revolution. Sansal wondered why the exiled Arab intellectuals who were not exposed to direct threats, did not show greater solidarity with their fellow countrymen.

Regarding the Israeli-Arab relations, the outcome of the Arab revolutions would be of great importance. Eli Amir expressed his disappointment that the Arab intellectuals who remained silent on the developments in their countries became instead highly critical of Israel. Exactly because he was seeking a dialogue with the Arab world, he wished that more Arab intellectuals dared to speak out just as critical of their own governments.

Smadar Perri summarized the discussion pointing out that the participating writers from the Middle East regarded their role more in political terms, whereas the European writers prefered to consider themselves as artists, even with a claim to be allowed to be apolitical. In the end, the political commitment of intellectuals did not fit into categories either black or white. For the audience, the discussion in Jerusalem was very instructive to learn about so many opinions. Although no one - whether writer or not - can remain morally neutral in such matters. Nevertheless, for those to whom the pen was available as a weapon special standards apply.

Palina Kedem and Motje Seidler. Translated by Nadine Mensel