Asset Publisher

Literaturpreis

Der Freiheit das Wort

Asset Publisher

Das Politische in der Literatur

Seit 1993 wird der vom ehemaligen Thüringer Ministerpräsidenten Prof. Dr. Bernhard Vogel ins Leben gerufene Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in Weimar vergeben. In kürzester Zeit ist der Preis zu einer festen Größe im literarischen Leben in Deutschland und darüber hinaus geworden. Geehrt werden Autoren, die der Freiheit ihr Wort geben. Die Auszeichnung wird jährlich in Weimar vergeben.

Der Literaturpreis bringt in besonderer Weise das Selbstverständnis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung zum Ausdruck, die es sich zur Aufgabe macht, politisches Handeln an den Grundwerten der Freiheit und des Friedens zu orientieren, Politik in Offenheit und Toleranz zu praktizieren und Begabungen von wissenschaftlicher und von öffentlicher Relevanz zu fördern.

Unsere Kriterien

Grundsätzlich können veröffentlichte literarische Arbeiten aller Gattungen ausgezeichnet werden. Voraussetzung ist, dass die Autorinnen und Autoren der Freiheit ihr Wort geben. Somit ehrt der Preis Autorinnen und Autoren, die sich dafür einsetzen, der Freiheit und Würde des Menschen zu ihrem Recht zu verhelfen, und deren Werke – das sind die Hauptkriterien der Preisvergabe – sowohl von politisch-gesellschaftlicher Bedeutsamkeit als auch von ästhetisch-literarischer Qualität zeugen. Die Preisträger reden keiner Partei das Wort, sondern bemühen sich um einen offenen und konstruktiven Dialog zwischen Literatur und Politik.

Unsere Jury

Die Preisträger werden von einer Jury ermittelt, die ab 2024 unter dem Vorsitz von Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Marx tagen wird. Externe Vorschläge für Kandidatinnen und Kandidaten können nicht angenommen werden. Die Meinungsbildung der Jury erfolgt frei, unabhängig und allein auf der Grundlage ihrer fachlichen Kompetenz.

Mitglieder der Jury im Überblick

Prof. Dr. Friedhelm Marx ist Literaturwissenschaftler an der Universität Bamberg (Vorsitzender der Jury)

Prof. Monika Grütters Mitglied des Deutschen Bundestages | Wahlkreis Berlin-Reinickendorf

Staatsministerin für Kultur und Medien a. D.

Dr. Marit Heuß ist Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin im Fachbereich Neuere deutsche Literatur und Literaturtheorie am Institut für Germanistik der Universität Leipzig

Sandra Kegel ist verantwortliche Redakteurin im Feuilleton der F.A.Z.

Prof. Dr. Birgit Lermen ist emeritierte Professorin an der Universität zu Köln (Ehrenmitglied)

Dr. Wolfgang Matz ist Literaturwissenschaftler und Übersetzer

Unsere Preisträger

Die Preisträger sind Orientierungsinstanzen in Zeiten des Wertewandels. Sie haben, wie es in der Präambel unserer Satzung heißt, der Freiheit das Wort gegeben. Daß es die Freiheit auch und gerade heute, in Zeiten von Gewalt und Terror zu verteidigen gilt, haben alle Preisträger in ihren Werken deutlich gemacht. Auf sie bezieht sich der Appell des spanischen Schriftstellers Jorge Semprúns, dass nun „Gedächtnis und Zeugnis Literatur werden“ können und werden sollen.

Für die Laudationes auf unsere Preisträger haben wir hoch angesehene Persönlichkeiten aus Wissenschaft und Politik, aus der Literatur und den Medien gewinnen können. Auch die Laudatoren haben den Preis und seinen Wert beeinflußt. Ihre Reden sind, bei allen Unterschieden in der Rhetorik und Zugangsweise, persönliche Würdigungen des Preisträgers.

2025

Die Preisträgerin: Iris Wolff

Jurybegründung: Die 1977 in Hermannstadt geborene, im Banat und in Siebenbürgen aufgewachsene, seit 1985 in Deutschland lebende Iris Wolff ist eine Autorin, die mit poetischer Eleganz und in dichten Szenen von Lebensformen der Freiheit erzählt. Angesichts der Schrecken der Ideologien des 20.Jahrhunderts halten ihre Romane Zeichen von Menschenfreundlichkeit und Werteverbundenheit fest. Sie schildern geschundene Biografien unter dem Eindruck europäischer Geschichte, orientiert an Figuren, die aus dem Banat und anderen Regionen Rumäniens vor und nach dem Regime Ceaușescus fliehen oder auch dort bleiben, die nach Zugehörigkeit und Heimat fragen und die Vielfalt von Sprachen und Religionen in Europa erfahren. Iris Wolffs Romane (jüngst „Die Unschärfe der Welt“, 2020, und „Lichtungen“, 2024) sind Lichtblicke in die Zeitgeschichte und ein wegweisender Beitrag zur europäischen Erinnerungskultur.

2024

Die Preisträgerin: Ulrike Draesner

Ulrike Draesners Großeltern kamen nach 1945 „flüchtlingsfremd“ aus Schlesien in Bayern an. Nach dem Studium der Rechtswissenschaft, Anglistik und Germanistik in München, u.a. bei dem ehemaligen Vertrauensdozenten und ersten Literaturpreis¬laudator der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, dem Germanisten Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Frühwald, und in Oxford hat Ulrike Draesner 1992 eine mediävistische Doktorarbeit geschrieben.

Sie hatte mehrere Poetik- und Gastdozenturen inne, in Birmingham und Oxford, Bamberg, Wiesbaden, Heidelberg und Frankfurt am Main (2017). Sie ist Mitglied der Berliner Akademie der Künste, der Nordrhein-Westfälischen-Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste und der Darmstädter Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung. Seit 2018 ist sie Professorin für deutsche Literatur und literarisches Schreiben an der Universität Leipzig und Erasmus-Koordinatorin am dortigen Deutschen Literaturinstitut.

Jurybegründung: „Ulrike Draesner hat ein außerordentlich vielfältiges prosapoetisches und multimediales Werk vorgelegt. Es besteht aus Romanen und Erzählungen, Essays und Reiseberichten, Lyrik und Libretti, Rundfunkarbeiten und Kurzvideos.

Ihre literarischen Leitthemen reflektieren aktuelle politische Diskurse der Zeitgeschichte: das transnationale Gedächtnis von Flucht, Vertreibung und Exil (in der Trilogie); das soziale Wechselspiel der Geschlechterrollen und die Frage nach der eigenen Identität (in den Erzählungen Hot Dogs, 2004, und Richtig liegen, 2011); die Rolle von Sprache und Liebe im Anthropozän (in den Romanen Vorliebe, 2010, und Mitgift, 2002); die Auseinandersetzung mit Reproduktionstechniken (Organverpflanzung, Genbiologie, Datenspeicherung) und mit dem Menschenbild der Hirnforschung und der Transplantationsmedizin (in Essays und Gedichten); das Herausschreiben der Kunst aus der Tradition (in ihrer Migration und Populismus verarbeitenden Nachdichtung Nibelungen. Heimsuchung, 2016); die Verantwortung des Menschen für die Natur im Anthropozän (Der Kanalschwimmer, 2019).

Aus Ulrike Draesners Werk ragt die oben schon genannte Romantrilogie über die europäische Gewaltgeschichte heraus. Sie zieht darin eine nachhaltige Summe aus der Trauer- und Trauma-Geschichte von Flucht und Vertreibung im 20. Jahrhundert. Sie selbst zählt sich, im Anschluss an Sabine Bodes Kriegsenkel (2009), zu den „Nebelkindern“, die im Schweigen der Kriegskinder und Kriegs-Zeitzeugen groß wurden. Die Verwandelten wurde in der Kritik als Roman gewürdigt, der das Gedächtnis der Generationen erneuert: über Mütter im Krieg, verwandelte Töchter und aufklärende „Nebelkinder“, eine Geschichte über starke weibliche Biographien und über die Gewalt, die ihnen in der europäischen Zeitgeschichte angetan worden ist. Draesners Spiele (2005) ist der erste Roman der deutschen Literatur über das Terrorattentat in München 1972, den globalen Terrorismus und Verschwörungs¬theorien nach 9/11.

In formaler Virtuosität, nach intensiver biographischer Recherche und mit enormer poetischer Imagination zeugt Ulrike Draesners Schreiben von der Freiheit der Kunst. In ihrem Roman Schwitters setzt sie mit Schwitters‘ Merz-Bau jener Freiheit der Kunst in der Weimarer Republik ein Denkmal, die durch die antisemitische Eliminierung jüdischen Lebens abgebrochen wurde. Zu ihrem Schreiben sagte sie in den Bamberger Vorlesungen Zauber im Zoo (2007): „Das Recherchierte, das bereits Fiktion ist (Auswahl, Bericht, Konstruktion einer Geschichte) muss über-erfunden werden in Atmosphäre und inneres Verstehen. Gedächtnis und Wahrnehmung, Zeugenschaft und das Zielen auf Wirklichkeiten rücken – uns – in den Blick“.

Ulrike Draesners Werke halten – mit hochentwickeltem Sprachbewusstsein – die literarischen Signale politischer Vorgänge in Zeitenwenden fest und bestärken die Erneuerungskraft der Literatur: „Wir sind hineingeflogen worden in eine Zeit, in der das Beharren auf Kultur wieder nötig sein wird“, schreibt sie in ihrem Essay über Thomas Mann, 2002). Und in dem Gespräch über Deutschland (2024) das sie mit dem New Yorker Übersetzer und Philosophen Michael Eskin geführt hat, plädiert sie für eine „critical Germanness“. Das meint für sie aber kein kritisches, sondern ein kundiges „Deutschsein, das erlaubt, Geschichten zu erzählen statt Etiketten zu verteilen“, „ein Deutsch mit Zusätzen, mit Geschichte, mit Verantwortung, Anerkennung von Differenz – und mit Humor statt Reinheitsgebot“, auch und besonders sprachlich.“

2023

Der Preisträger: Lutz Seiler

Was hat Lutz Seiler in Adenauers Schuppen zu suchen? Wie kommt er zu den Bildern, von denen er erzählt? Wohin strahlen seine Romane und Gedichte aus? Und welche Rolle überhaupt spielt Literatur in Wendezeiten? Antworten gibt die Dokumentation des Literaturpreises der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 2023. Sie enthält, nach dem Grußwort von Norbert Lammert, die Laudatio der Kunsthistorikerin Marion Ackermann, die Dankrede Lutz Seilers und ein Interview mit dem Autor.

Jurybegründung: „Lutz Seiler gilt als rundum gewichtiger Autor, dessen Werke von poetischer Sprachkraft und zeitpolitischer Intensität zeugen. Sowohl in der Lyrik (zuletzt ‚schrift für blinde riesen‘, 2021), in den Essays und vor allem in den größeren Prosawerken, den beiden Romanen ‚Kruso‘ und ‚Stern 111‘, die kurz vor und nach dem Mauerfall spielen, hat er der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur neue Impulse gegeben. Seine literarische Aufarbeitung des Übergangs von der DDR zur Bundesrepublik Deutschland ist überraschend anders, politisch sensibel und literarisch hochinnovativ. Er erzählt von der Neuordnung der Menschen in einer Zeitenwende und davon, wie Freiheit angesichts von großem politischem Normenwandel möglich ist.“

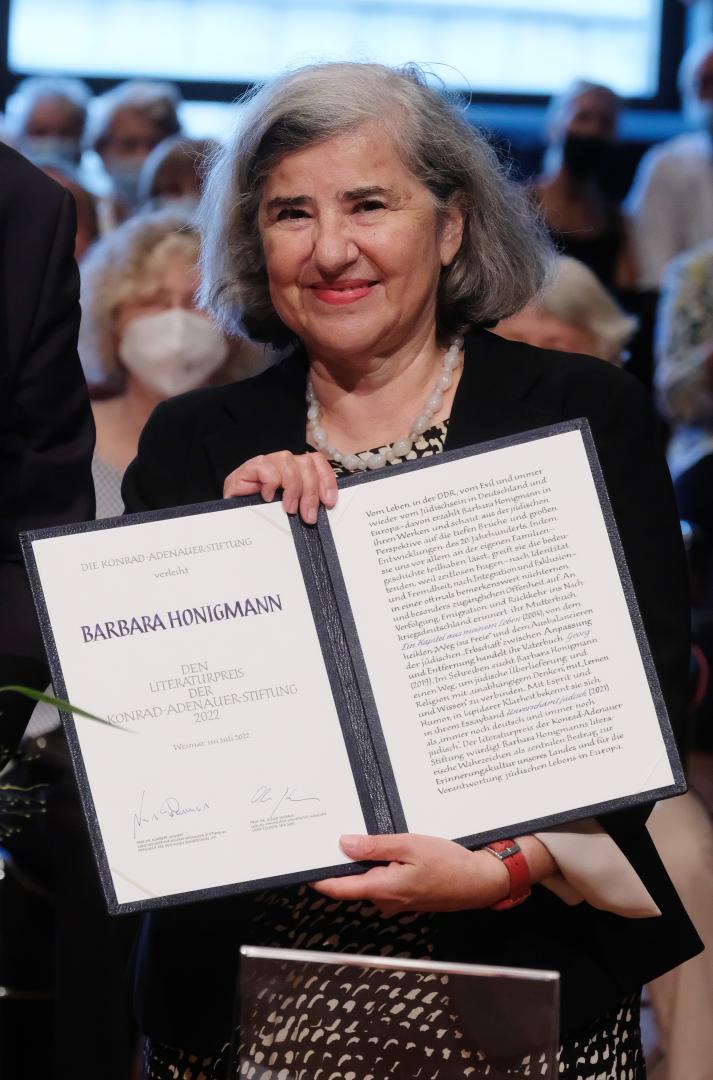

2022

Die Preisträgerin: Barbara Honigmann

Vertrauen in die jüdische Biographie, Vertrauen in die deutsche Sprache und die europäische Kultur: Das hob der Stiftungsvorsitzende Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert bei der Verleihung des Literaturpreises der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung an Barbara Honigmann am 3. Juli 2022 hervor. Die mit 20.000 Euro dotierte Auszeichnung wurde – nach zweijähriger Corona-Pause – wieder im Musikgymnasium Schloss Belvedere in Weimar verliehen. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Raphael Gross, Präsident der Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Jurybegründung: „Barbara Honigmann erzählt Kapitel aus der Geschichte des Exils, der DDR und des Judentums in Deutschland und Europa. Ihre jüdische Perspektive auf die großen politischen Verwerfungen des 20. Jahrhunderts wirft in besonderer Weise die Fragen nach Identität und Fremdheit, nach Integration und Ausschluss auf. Barbara Honigmanns Romane und Essays (zuletzt das Vaterbuch Georg, 2019, und der Essayband Unverschämt jüdisch, 2021) sind Bekenntnisse zur Migrationsgesellschaft, Chronik ihrer Familienhistorie und Narrative einer jüdischen Kultur, die sich als ‚kosher light‘ versteht und nach eigenen Worten einen neuen Ort jenseits eines ‚immerwährenden Antisemitismus-Diskurses‘ sucht. Mit Witz und leichthändigem Humor, in lapidarer Klarheit, ohne „das Unmögliche, das Unstimmige“ auszuklammern (Dankrede zum Kleist-Preis), porträtiert Barbara Honigmann das literarische Gesicht unserer Zeit.“

2021

Aufgrund der COVID-19-Pandemie wurde der Preis im Jahr 2021 nicht vergeben.

2020

Der Preisträger: Hans Pleschinski

Wer eine Botschaft hat, soll Hemingway gesagt haben, solle zur Post gehen. Hans Pleschinski sieht das offenbar anders. Mit seinen Botschaften von einer anderen, positiv besetzten europäischen und deutschen Geschichte bedankte er sich am Freitagabend, dem 5. November, für den Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Der Stiftungsvorsitzende Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert hieß den Preisträger in der Berliner Akademie der Stiftung als heiter aufgeklärten Europäer willkommen, der in seinen Romanen und Übersetzungen „Geschichte verlebendige“.

Jurybegründung: „Hans Pleschinskis Erzählungen, seine Übersetzungen, Brief- und Tagebuch-Editionen aus dem Zeitalter Voltaires, dessen aufgeklärte Heiterkeit auf sein eigenes Schreiben ausstrahlt, verlebendigen eine zivilisierte Gesprächskultur. Der Roman Brabant (1995) versammelt die demokratischen Europa-Diskurse im Bild einer vielfältigen, multinationalen Kulturgesellschaft. Den Romanen Königsallee (2013) über Thomas Mann und Wiesenstein (2018) über Gerhart Hauptmann gelingt es, Nachkriegszeit und junge Adenauer-Republik in den späten Biographien der Nobelpreisträger wachzurufen. Hans Pleschinski erzählt davon, wie viel uns die Freiheit wert ist, indem er angesichts der politischen Herausforderungen unserer Zeit eine ethische Verantwortung für gute Ordnung, für Recht und Freiheit übernimmt.“

2014 und früher

2019

Der Preisträgerin: Husch Josten

Am 16. Juni 2019 wurde Husch Josten in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Thomas Sternberg, Präsident des Zentralkomitees der deutschen Katholiken (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2019 - Gesamtdokumentation

2018

Der Preisträger: Mathias Énard

Am 6. Mai 2018 wurde Mathias Énard in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Generalsekretärin der CDU (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2018 - Gesamtdokumentation

2017

Der Preisträger: Michael Köhlmeier

Am 25. Juni 2017 wurde Michael Köhlmeier in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt die Kultur- und Literaturwissenschaftlerin Prof. Dr. Aleida Assmann.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2017 - Gesamtdokumentation

2016

Der Preisträger: Michael Kleeberg

Am 05. Juni 2016 wurde Michael Kleeberg in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Jürgen Flimm, Intendant der Deutschen Staatsoper Unter den Linden (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2016 - Gesamtdokumentation

2015

Die Preisträgerin: Marica Bodrožić

Am 31. Mai 2015 wurde Marica Bodrožić in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Literaturwissenschaftler und Autor Rüdiger Görner.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2015 - Gesamtdokumentation

2014

Der Preisträger: Rüdiger Safranski

Am 31. Mai 2014 wurde Rüdiger Safranski in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Monika Grütters, Staatsministerin für Kultur und Medien des Landes Berlin (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2014 - Gesamtdokumentation

2013

Der Preisträger: Martin Mosebach

Am 23. Juni 2013 wurde Martin Mosebach in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Literaturwissenschaftler, Übersetzer und Lyriker Dr. Heinrich Detering.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2013 - Gesamtdokumentation

2012

Der Preisträger: Tuvia Rübner

Am 10. Juni 2012 wurde Tuvia Rübner in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Schweizer Schriftsteller und Literaturwissenschaftler Prof. Dr. Adolf Muschg.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2012 - Gesamtdokumentation

2011

Der Preisträger: Arno Geiger

Am 18. September 2011 wurde Tuvia Rübner in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt die Literaturkritikerin, Autorin und Journalistin Dr. Meike Feßmann.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2011 - Gesamtdokumentation

2010

Der Preisträger: Cees Nooteboom

Am 12. Dezember 2010 wurde Cees Noteboom in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert, Präsident des Deutschen Bundestages (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2010 - Gesamtdokumentation

2009

Der Preisträger: Uwe Tellkamp

Am 06. Dezember 2009 wurde Uwe Tellkamp in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Philosoph und Theologe Prof. Dr. Richard Schröder (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2009 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

2008

Der Preisträger: Ralf Rothmann

Am 18. Mai 2008 wurde Ralf Rothmann in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielten der Theaterregisseur und Intendant Matthias Hartmann sowie der Autor und Dramaturg Dr. Thomas Oberender.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2008 - Gesamtdokumentation

2007

Die Preisträgerin: Petra Morsbach

Am 10. Juni 2007 wurde Petra Morsbach in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Dr. Jiří Gruša, Direktor der Diplomatischen Akademie Wien und Präsident des Internationalen PEN (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2007 - Gesamtdokumentation

2006

Der Preisträger: Daniel Kehlmann

Am 18. Juni 2006 wurde Daniel Kehlmann in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Mathematiker Prof. Dr. Roland Bulirsch.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2006 - Gesamtdokumentation

2005

Der Preisträger: Wulf Kirsten

Am 22. Mai 2005 wurde Wulf Kirsten in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Autor, Jurist und Kulturhistoriker Dr. Manfred Osten, ehemaliger Generalsekretär der Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2005 - Gesamtdokumentation

2004

Die Preisträgerin: Herta Müller

Am 16. Mai 2004 wurde Herta Müller in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Dr. Joachim Gauck, Vorsitzender des Vereins "Gegen Vergessen – Für Demokratie" (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2004 - Gesamtdokumentation

2003

Der Preisträger: Patrick Roth

Am 22. Juni 2003 wurde Patrick Roth in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Ruprecht Wimmer, Präsident der Katholischen Universität Eichstätt und Präsident der Thomas-Mann-Gesellschaft (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2003 - Gesamtdokumentation

2002

Der Preisträger: Adam Zagajewski

Am 02. Juni 2002 wurde Adam Zagajewski in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Dr. Martin Meyer, Leiter des Feuilletons der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2002 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

2001

Der Preisträger: Norbert Gstrein

Am 13. Mai 2001 wurde Norbert Gstrein in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Schriftsteller und ehemalige spanische KulturministerJorge Semprún.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2001 - Gesamtdokumentation

2000

Der Preisträger: Louis Begley

Am 14. Mai 2000 wurde Louis Begley in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Historiker, Museologe, Publizist und Politiker Prof. Dr. Christoph Stölzl.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 2000 - Gesamtdokumentation

1999

Der Preisträger: Burkhard Spinnen

Am 16. Mai 1999 wurde Burkhard Spinnen in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Annette Schavan, Ministerin für Kultus, Jugend und Sport in Baden-Württemberg (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1999 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

1998

Der Preisträger: Hartmut Lange

Am 10. Mai 1998 wurde Hartmut Lange in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Philosoph und Essayist Dr. Odo Marquard.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1998 - Gesamtdokumentation

1997

Der Preisträger: Thomas Hürliman

Am 03. Juli 1997 wurde Thomas Hürliman in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Regisseur, Manager, Kulturpolitiker und Intendant Prof. Dr. August Everding.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1997 - Gesamtdokumentation

1996

Der Preisträger: Günter de Bruyn

Am 15. Mai 1996 wurde Günter de Bruyn in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Vorsitzender der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion und Mitglied im Bundesvorstand der CDU Deutschlands (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1996 - Gesamtdokumentation

1995

Die Preisträgerin: Hilde Domin

Am 11. Mai 1995 wurde Hilde Domin in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der deutsch-polnischer Autor, Publizist und Literaturkritiker Dr. Marcel Reich-Ranicki.

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1995 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

1994

Der Preisträger: Walter Kempowski

Am 03. Mai 1994 wurde Walter Kempowski in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt der Politikwissenschaftler, Publizist und Politiker Prof. Dr. Hans Maier (CSU).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1994 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

1993

Die Preisträgerin: Sarah Kirsch

Am 15. Mai 1993 wurde Sarah Kirsch in Weimar mit dem Literaturpreis der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ausgezeichnet. Die Laudatio hielt Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Frühwald, Literaturwissenschaftler, Hochschullehrer und Präsident der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung).

Zum Sammelband Literaturpreis 1993 - Gesamtdokumentation

(Printversion vergriffen, Online-Version nicht verfügbar)

Biographien und Werdegänge unserer Preisträger

Auf der nachfolgenden Karte finden Sie eine Übersicht mit Biographien und Werdegängen aller unserer Preisträger.

Interaktive Karten

Sarah Kirsch

* 16 April 1935 in Limlingerode

† 5 May 2013 in Heide

"Sad day" - Obituary

Sarah Kirsch was the first recipient of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation Literature Prize in May 1993. The location of the award was in accordance with her wish that it should be as close as possible to her birthplace, Limlingerode in the southern Harz region. At the ceremony in the Goethe House in Weimar, she replaced the ritual speech of thanks with the poetic word. Reading poetry was, in Sarah Kirsch's own words, what she did "best". The poet passed away on 5 May 2013.

Sarah Kirsch's literary work, which is available in complete editions from the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and in a recently still growing series of fascinating short prose volumes, was appreciated by critics and laudators, by fellow authors and by Germanists - and above all by enthusiastic readers. The poet has received numerous awards, and a little too late the Büchner Prize in 1996. Her first book, the poetry collection "Landaufenthalt" from 1967, set the theme that has guided her ever since: man's relationship to nature in disrepair.

Man and Nature in the Anthropocene

"Anyone who writes poems that assume that the world is whole is throwing sand in the eyes of themselves and others". True to this self-statement, Sarah Kirsch's poetry is anti-idyllic, it requires "thoughtfulness and patience", as her laudator Wolfgang Frühwald emphasised in Weimar. What Sarah Kirsch wrote in the 1980s about the "dying trees, holes in the firmament, the air becoming hopeless and the poisoned waters of the earth" sounds like an anticipated chronicle of today's climate catastrophe reports. No one has been so clear-sighted - and at the same time aware of the beauty of suffering nature - in naming the "gentle horror" (Adalbert Stifter) and the often invisible risks of the Anthropocene.

At the heart of her work is the human being, who is just as responsible for the state as for his environment. There is no separation between man and citizen, public and private. "If I had no political interests, I could not write verse," she once confessed. But these interests are not political plain language, but poetic statements, formulated pictorially and designed to be thought about, not prayed after.

That is why Kirsch's language is brittle and concise. She reduces poetry to the bare minimum. This language is wonderful - and that is certainly in the sense of magical verses and "Zaubersprüche" (which is the name of her perhaps most beautiful volume of poetry, along with "Erlkönig's Daughter", published in 1973) - because it knows how to unite the incompatible with a light hand. From North German dialect, archaic expression, historical or fairy-tale sprinklings, brash idioms, intelligent language games and delicate images, the much-praised "Sarah sound" emerges.

Biography

Sarah Kirsch was born under the name Ingrid Bernstein on 16 April 1935 in the Limlingerode vicarage, her grandfather's "last official residence" before retirement, as she writes in her autobiographical childhood story "Kuckucksnelken" (2006). With the elective name "Sarah" she protests against the great injustice done to the Jews in Germany. Her studies in biology, which she began after working for a year in a sugar factory in Halle and graduated with a diploma in 1959, sharpened her eye for nature. She learned the literary craft from 1963 to 1965 in Leipzig, at the then Institute for Literature "Johannes R. Becher". Far from any literary school, she wrote non-conformist poems and cheeky gender-swap stories ("Die Pantherfrau", 1974). Living in East Berlin since 1968, she organised East-West writers' meetings with colleagues across the inner-German border in the 1970s, where manuscripts were read and discussed; also in her own flat, a high-rise on Berlin's Fischerinsel. Friend and colleague Hans Joachim Schädlich reports that the preparations for the meetings were bugged by the Stasi.

But not what the authors read. "The content of the consultations could not be clarified," it says helplessly in the Stasi files. How could they! In the poem "Sad Day" from 1967, which is still in school reading books, the poet prances through the walled city, literally "like a tiger in the rain", she roars "at the Alex the rain sharp" and joins the "honest" seagulls on the Spree, her gaze turned to the left, i.e. west. "And when I howl like a mighty tiger / You understand: I think there should be / Other tigers here".

But they didn't exist back then. The state security, as omnipresent and terrible as it was, did not understand this in a frightening way. When in 1976 there was finally a howl of protest from the powerful of the word, when Reiner Kunze's "Wunderbare Jahre" (Wonderful Years) was published in the West, when Wolf Biermann was expatriated and the authors, first and foremost Sarah Kirsch, protested against this to the GDR's state leadership, the state in turn responded with enormous harassment.

At the time, Sarah Kirsch saw no other way out than to move away "from the house of the city to the country / And maybe even further for ever". In 1977, on 28 August, Goethe's birthday, she left the GDR with her son, carrying the application for emigration that had just been approved. She does not shed a tear for what she sees as a "thank goodness! sunken German democratic GDR". She was one of the most implacable critics of the "Ostalgics", who continued to rave about a GDR that could have been, but in reality never was.

After an intermezzo in West Berlin (1977 to 1983), Sarah Kirsch settled in Tielenhemme in Schleswig-Holstein, where she lived until her death. There she lived in a schoolhouse with many cats, wrote with "sepia ink from the inkwell for old-fashioned fountain pens" (but also with her laptop), painted watercolours, wandered through the moorland meadows and fields and travelled, as long as she could, preferably northwards, from which emerged such beautiful journals as the diary fragments from "Islandhoch" (2002) or from "Regenkatze" (2007).

In the journal "Märzveilchen" (March Violets) (2012) there is an entry in January 2002: "Mrs Lindgren has died, at 94. She gets a wonderful star where she can settle down, who else". What remains of Sarah Kirsch, who died at 78, are her poems, her prose, her watercolours.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2013

Walter Kempowski

* 29. April 1929 in Rostock

† 5. October 2007 in Rotenburg an der Wümme

Literature as Memory - Obituary

Haus Kreienhoop is a large estate in a small village in Nartum, Lower Saxony. Here, in his 700 square metre book ark, Walter Kempowski lived and wrote his collective chronicle "Das Echolot". For the first four volumes of the nine-volume work, which is unparalleled in contemporary German literature, Walter Kempowski received the Literature Prize of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation on 3 May 1994, just "at the right time", as the author said in his acceptance speech. On 5 October 2007, the great German and European chronicler succumbed to cancer in Rotenburg hospital.

Biography

"Das Echolot" has made Kempowski a respected author. He had been known for a long time, as documented in the recent exhibition "Kempowski's Curriculum Vitae" at the Berlin Academy of the Arts. Born in 1929 as the son of a Rostock shipowner, he was arrested three years after the end of the war for alleged espionage and sentenced to 25 years in Bautzen. He spent eight years behind the bars of the "Yellow Misery". In the prison yard, he listened to the diverse buzzing in the cells. The many unknown voices: Who listens to them, who collects them, who passes them on? This is the starting point of "Echolot": "We have to pick up what must not be forgotten ... It is our history that is being negotiated there".

After eight years, Kempowski was released, went to Göttingen to study literature and then worked as a village teacher in Nartum for 20 years. He must have been a quirky and whimsical teacher, as if sprung from the novels of Jean Paul, instructive without being lecturing, witty but often far removed from the fashions of the zeitgeist. In 1975, his best-known novel, "Tadellöser und Wolff", was published and later successfully filmed, a history of the fate of the German bourgeoisie in the 20th century. The theme of the German chronicle never left him. The moral contortions with which everyday life in the "Third Reich" was survived, he knew how to describe just as vividly as one of the Germans' main blights, the flight from their historical responsibility, their inability to remember accurately, their problems in dealing with freedom.

Remembrance literature avant la lettre

Kempowski spent almost a quarter of a century on "Echolot", the longest and best writing time of his life. The work is a collage of documents, letters, biographies, diary excerpts from the National Socialist era, intra et extra muros. Diary notes by Goebbels stand next to autobiographical notes by Thomas Mann, Allied orders by Churchill next to letters by unknown soldiers. The focus of memory is on Stalingrad and Auschwitz, the epicentres of perpetrator memory and victim memory on the European continent of memory. The voices of war participants, refugees, emigrants, Jews and Allies form a heterogeneous compendium of their time and make a better and more exciting history book than any historiographical monograph. Kempowski allows the contemporary witnesses their original voice, their suffering of Germany in the war, their hope for a more peaceful Europe.

The author's retreat from the collage of quotations has occasionally been interpreted as a loss of originality. The opposite is true. Walter Kempowski does nothing other than what Walter Benjamin had in mind in his "Passagenwerk": to record a great human tragedy in original tones. The author's art as a director lies in selecting the collected voices and bringing them into a choreography in which they speak for themselves, with the other contemporary witnesses and at the same time to us, those born later. He pulls away, as Martin Mosebach clairvoyantly observed, the "moral curtain that withdrew the sublime senselessness of history from our eyes. He taught the Germans a historical view without a philosophy of history".

In this, the "Echolot" is highly topical. Kempowski counts on memory - and on the fact that someone hears it. This also applies to the sequel, which deals with the last weeks of the war in January and February 1945, including the Allied bombing of Dresden, and the volume "Abgesang, 1945", which concludes the gigantic project: it begins on the day of Hitler's birthday and ends with the total surrender of Nazi Germany. Kempowski's nine-volume work is memory literature in the best sense of the word; after the contemporary witnesses have died, it endows the future of memory from which we can learn: not how things actually were, but how people recorded and interpreted their time linguistically. Kempowski is the archivist, chronicler and narrator of European memory.

Latest works

"Letzte Grüße" (2003) and "Alles umsonst" (2006) are the names of the novels Kempowski wrote in the last years of his life. The titles are signals: not of a melancholy work of old age, but of a life under the sign of memory, which is so realistic that it always knows how to take into account its own failure, i.e. forgetting. The fact that it often deals with the tragedy of refugees and the misery of expulsion is rooted in Kempowski's own biography. With the honorary citizenship of his hometown Rostock, which according to the publisher also wants to hold an official memorial service for him, he has received a belated satisfaction.

In spite of his serious illness, Kempowski repeatedly held literary seminars and readings at Haus Kreienhoop - when he was no longer able, his wife continued to read - and received visitors, including the author of these lines in the summer of 2014: There he sat by the television, swatting at flies while listening to the critics at the Bachmann Competition in Klagenfurt. His "Echolot" plumbed the depths and shallows of 20th century German history. The 21st century can only learn from this literary historiography from below.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2007

Hilde Domin

* 27 July 1909 in Köln

† 22 February 2006 in Heidelberg

Poet of the Nevertheless

She always read her poems twice, even in Weimar, when she received the Literature Prize of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in 1995: once for her fellow world, once for posterity. They are lyrical legacies worth keeping and learning by heart. What Hilde Domin had to say to her contemporaries still applies today: It is not in vain to rebel undauntedly, to interfere confidently, even with humour, to write against pre-conformism ("if you want to be bedded down today as you would like to lie down tomorrow") and to put your foot down for more brotherhood - despite, or precisely because of, the unsolidarities all over the world.

Being uncomfortable was never Hilde Domin's problem. She liked to sit between the chairs. That was the place for her "courage for nevertheless" (Ulla Hahn). "Der Baum blüht trotzdem" (The Tree Blossoms Nevertheless) was the title of her last volume of poetry (1999). On 22 February 2006, the great Cologne poet died at the age of 96. Today, a plaque on the house where she was born in Riehler Straße commemorates Hilde Domin. Heinrich Böll lived around the corner. Her Cologne flat was so big that the children could run in the hallway on roller skates. Already at school, the early talent stood out. She wrote essays in rhyme and gave such a critical graduation speech in her father's lawyer's gown that the school administration considered revoking her diploma. When she took her oral examination at the Merlo-Mevissen grammar school in March 1929 under the chairmanship of the then Lord Mayor Konrad Adenauer and was downgraded one grade by the school board for her Pan-European commitment, she tore her dove-blue velvet dress at home in anger. She praised the first German Chancellor as a reconciler of peoples and a thinker on freedom in her Weimar acceptance speech in 1995, when she was awarded the Literature Prize of the Adenauer Foundation.

Hilde Domin's life story is inseparable from her exile. In 1932, she left Nazi Germany with her future husband, the Hispanic Erwin Walter Palm. Her father, a Jewish lawyer, had been publicly ridiculed by the Nazis. Via Italy and England, the student arrived in the Dominican Republic, a shady paradise. The dictator Trujillo hoped to "whiten" his country with the emigrants from Europe, but persecuted all dissenters.

In exile, Hilde Domin became a poet. In the posthumously edited letters with her husband, one can read how difficult this poetic self-birth was. Hilde Domin asserted herself not only in foreign linguistic milieus, but also against the ignorance of her husband, who would have liked to become a world-famous poet himself.

Hilde Domin returned to Germany in 1961. It was no coincidence that her first poetry reading took place in Cologne. The ballroom of the Cologne City Museum in Zeughausstraße was well filled. As Hilde Domin gazed at Appellhofplatz and the "court with the big new glass doors", she had the idea for the poem "Cologne". She dedicated it to Böll. It is a poetic document of flight and expulsion, a migration poem. "I swim in these streets," it says of what she sees as a "sunken city": "Others leave."

Hilde Domin's "Nevertheless" poems set signs of hope against all hope. For example, in the three songs of encouragement (1961). The first begins with the sad image of tear-soaked pillows with disturbed dreams. Then follows the "Nevertheless": "But again / from our empty / helpless hands / the dove rises". The hands are helpless, they are even empty. But the soaring dove is not a poet's magic trick, but a symbol of poetic trust. The bird is the sign of a miracle, of a very earthly grace that can befall man just as much as the greatest misfortune. That is why Domin's poetics of hope is not to be confused with faith. She is not a confessional poet. She is concerned with articulating fashionable experiences also from the Jewish and Christian exile tradition, examples with which the poet endeavours to address the politically alert, fraternally thinking person in the reader. This does not require many words or complicated language. Hilde Domin's "simple words" "smell of man". The core of this dialogical poetics is the trust that there is a You that allows itself to be called upon by an I.

The poem Sisyphus from 1967 is also revealing: an appeal beyond the philosophy of the absurd to roll the stone uphill even though it seems pointless; an encouragement to start anew. In this way, Hilde Domin's poems are "dispatches from the agency of practical reason", as Iso Camartin said on the occasion of the award of the Heidelberg Prize for Exile Literature to Hilde Domin (1992).

Hilde Domin's exile poems recall flight and expulsion, without melancholy, with the courage for nevertheless and for a second chance. Even the most critical of her colleagues have attested to what this chance consists of. It is Hilde Domin's "gentle courage" for a nonetheless that comes along on pigeon-toed feet, but leaves deep traces and confronts everything that prevents people from being human. "Gentle Courage" is the title of the nonetheless conversation that Erich Fried dedicated to her colleague in the 1980s: "You would even face death quietly!" - "Quietly? Perhaps. But face it." That is said "on the tipping point between fear and confidence. Balancing rod the ratio".

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2016

Günter de Bruyn

* 1 November 1926 in Berlin

† 4 October 2020 in Bad Saarow

Writer of Unity - Obituary

Günter de Bruyn is the fourth recipient of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation Literature Prize. In 1996, Wolfgang Schäuble, at that time leader of the parliamentary group of the CDU/CSU, gave him the laudation in the Weimar National Theatre. Günter de Bruyn passed away on 4 October 2020.

"Good as poetry" is how the Prussian King Frederick William III is said to have justified his rejection of a military memorandum. Günter de Bruyn loved and collected episodes like these. Why? Because they provide a wonderful, lightly ironic and at the same time instructive account of the relationship between literature and politics, from the heyday of Prussia to the reunified Germany. On 4 October, one day after the 30th anniversary of German unification, Günter de Bruyn died at the age of 93.

Günter de Bruyn was born in Berlin on 1 November 1926. He worked as a school teacher and as an academic librarian before he came to writing in the 1960s. De Bruyn critically examined his own beginnings. He later called his first novel "Der Hohlweg" a "wooden path". He was not afraid to put his own courage into perspective and to address the difficulties of writing the truth. This is vividly demonstrated in his novels. They are a distorting mirror of the socialist educational dictatorship and at the same time a lesson in free thinking. The scholarly satires "Buridans Esel" (1968), "Preisverleihung" (1972), "Märkische Forschungen" (1978) and the dementia novel "Neue Herrlichkeit" (1984) tell of how the GDR wanted to be and how it really was: realistic social novels by an author who was called the Fontane of the GDR.

When the Wall fell, Günter de Bruyn was on the side of the friendly admonishers. Between "cries of jubilation, songs of mourning" (this is the title of his 1991 volume of essays), he professed a position of German cultural nationhood, which, he argued, should rejoice with good reasons of freedom and peace, through which the unification of the long-divided country had come about. A "writer of German unity" is what Wolfgang Schäuble, then chairman of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, called the author in 1996 during his laudation at the Weimar National Theatre when he received the Literature Prize of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation there: for his autobiographical, essayistic and narrative works, which - according to the justification for the prize - "give the floor to freedom with quiet clarity, philanthropy and humour".

Günter de Bruyn has authenticated his cultural-political stance by presenting his autobiography about his youth in Berlin ("Zwischenbilanz", 1992) and his time in the GDR ("Vierzig Jahre", 1996). He writes circumspectly and with clear-sightedness about his life in two dictatorships, deals with false memories and, with Jean Paul, about whom he has written a biography that has been reprinted several times, chides the "strongmen" for "lacking the power of truth, i.e. resembling the buttercup which, because the cows don't eat it, 'never becomes butter'".

The autobiography is the joint that connects the novels of Phase I with the Prussian books of Phase II. Since the 1990s, Günter de Bruyn has distinguished himself as a researcher of Prussian history; he tells what the historian Christopher Clark describes: how Prussia, thanks to its culture, was a European state before it became a German one. De Bruyn's books deal with fates, books and people from Berlin's artistic epoch around 1800. They are about the magnificent avenue Unter den Linden, about the aristocratic Finckenstein family, about the charismatic Prussian Queen Luise. And, again and again, about Mark Brandenburg landscapes. "Abseits", the eloquent title of his 2005 book, from the culture industry, the author researched and wrote in a Brandenburg village where he had lived since 1967, true to the maxim of Chamisso, whom he admired: "in these frenzied times I withdraw in humility".

Security, freedom and peace in the state are based on literature. Günter de Bruyn has intensively reassured us of this in his novels and historical narratives. With his latest book, Günter de Bruyn has returned to the novel. "Ninety Years" (2018) is set in August 2015, in the middle of the year of the welcome culture. The novel tells of a long life in the short 20th century and the lessons from history for the present; it is about Catholic faith and the need for conscience, fear of progress and courage for the tried and tested, about the limits of gendering and the beauty of the German language: "As poetry good".

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2020

Thomas Hürlimann

* 21 December 1950 in Zug

Domestic correspondent, doomsday researcher and "world theatre" author

A fifteen-year-old monastery student climbs into the roof truss of the monastery church during Sunday mass. There he folds a paper aeroplane and lets it sail through the small opening in the dome into the crowded nave. On the paper is written: "Religion is the will to hibernate".

Biography

The boy who takes his test of courage for the "Club of Atheists" in this way is Thomas Hürlimann. Born in Zug, Switzerland, in 1951, he spent his school years (1963-1971) at the Einsiedeln Stiftsgymnasium, where he found "heaven a lid, religion a terror". One can imagine how the flying Nietzsche quote hit the church community at the time. "Two years later, Anno 1968," Hürlimann writes, "we occupied the rector's office and burned our frocks. We demanded free exit, we wanted to eat French fries and drink Coke and listen to the Stones."

At the end of the seventies, Thomas Hürlimann witnessed the death of his 20-year-old brother Matthias, which lasted for weeks. He got this existential horror of death off his chest in his first novella, Die Tessinerin. The novella tells a story about the limits of life, hauntingly, with high precision and cinematically precise editing ("the cut determines the style", Hürlimann once wrote). With The Ticino Girl, Egon Amman opened his Zurich publishing house, to which Hürlimann remained loyal until its dissolution in 2010.

Family and Doom Research

The key experience of dying is at the centre of Thomas Hürlimann's works. It is inextricably linked to the theme of the family whose story is always told - his family. Thomas Hürlimann is one of those authors who do not invent their material, but find it: in family stories that are transformed into literature. The brother, the father, the mother, the uncle (the monastery librarian of St. Gallen): They have died, most recently the prelate. But they live on - in the stories told by the writer's son. The parents play roles under their real names in the first play Grandfather and Half-Brother (1980). The novels Der große Kater (The Big Cat, 1998) and Vierzig Rosen (Forty Roses, 2006), together with the novella Fräulein Stark (Miss Stark, 2001), form an autobiographically based Swiss family genealogy, with glamour and misery, as it has been similarly told in other contemporary European novels, for example by Peter Esterhazy, but perhaps nowhere as intrinsically Swiss as here. That is why anyone who only deciphers the real references of the novels and disregards their symbolic added value is on the wrong track. Thomas Hürlimann, the "domestic correspondent", is a master of leitmotif chains of reference and multi-coded images.

The death of the family, death in the family: the binding agent that holds this theme together is doom. The "doom researcher" Thomas Hürlimann, who not only takes words seriously but literally, has explained this word thus: the "doom" comes "from the coachman's fear of the carriage running away. If it chases towards the abyss, it drags the carriage along - it is hung up with the horses". And the main fate of our globally networked age is time, the immense acceleration of which is no longer even perceived when zapping through more than a hundred television channels and real-time communication on the internet. Time, writes Hürlimann, "is only rarely struck by bells", it no longer flows, but stands still in the digit, the smallest electronic unit of information, point by point.

Many of Hürlimann's stories and plays begin with death entering a community, in the truest sense - as the doctor says, "Death has entered", an uninvited, secretive, family façade-breaking guest, perhaps The Last Guest, as in the 1990 play of the same name. Death does not let anyone rest in peace in Hürlimann's works, certainly not the one who looks the other way and leaves him to the hospital rooms and palliative high-performance medicine. There are several references to the eyes of the deceased being glued shut with a sticking plaster: "If a person dies, the world dies", it says. The eye gaze of death is the blind spot of our perception of the world.

Comedies in Weh-Dur

Hürlimann is concerned with saving human dignity in the face of death. His dances of death are symbols of the fragile institution of the family, whose structure has been described with terms like "patchwork", "exceptional phenomenon", "residual family in the welfare state". This family has not been holy for a long time. The primordial situation of this deified late modernity is found in the 1996 play Carleton. The agronomist Carleton has returned to his hometown of Kansas City, to whom America owes the weather-resistant Russian wheat, but instead of a triumphant welcome, the backyard milieu of a city without a church and with a God who now only hides in grain and money awaits the homecomer. Thus the metaphysical antennae of many of Hürlimann's characters fidget into nothingness. "Heaven was closed, God was declared dead, and that was possible because people no longer needed him as a giver of being," sums up the little poetology Das Holztheater (1997). But the author is not an adept of a Propositional tradition or one trimmed to Christian reconciliation; he stands between Rolf Hochhuth and Thomas Bernhard, between Christian modernised tragedy and grotesque "comedy tragedy". His plays, a theatre critic has said, are "comedies in the major of woe".

Hürlimann's favourite means of making the serious bearable is situational comedy. His humour is sometimes abysmal, especially when it concerns political or religious issues. For example, in the short story "The Tunnel" (dedicated to Dürrenmatt), when the celebrating and poker-playing politicians in the federal jubilee year of 1991 make grandiose appearances in their special train, but have no possibility of leaving, i.e.: a toilet - their audience is schoolchildren who, when the train has put on the emergency brakes and every man has come out, belt out the national anthem, "but with closed eyes". Or when (in The Big Hangover) the apostolic nuncio turns religious questions into culinary ones underhandedly at the Swiss president's gala dinner, illustrating divine providence with the dessert - all the invited guests are sure - undoubtedly served at the end. The figures of Thomas Hürlimann's "Catholic atheist", who in the famous questionnaire of the F.A.Z. cites the "transition from corset to lingerie" as the most admired reform, these figures of Hürlimann are not despisers of sensual knowledge. (By the way, a Zurich brewery is named after the author, as proof I can show you the matching beer mat later).

Even in Satellite Town, the story collection published in 1992, there is no room for religious feelings, Christian miracles or biblical transformations. The humoresque "Onkel Egon und der Papst" (Uncle Egon and the Pope) demonstrates how television conquers living rooms at the end of the 1950s as an epiphany of media modernity. It is revered there like a supreme being. The viewers' prostration is not to the Pope, who gives the urbi et orbi blessing on the screen; no, they fall down before the medium, the "miracle of television". This is a significant and basically tragicomic situation. The "miracle of transformation" has shifted from the Mass to the media. On this secular stage of transformation, Hürlimann discovers the comedy in traditional tragedies, especially in those of the Bible.

Thomas Hürlimann went to school with authors of the absurd theatre. In this he is closer to Beckett than to Brecht. Dissonance and dialectics are the structural laws of his plays. They do not want to improve through laughter, only to give insight. That is why the early didactic plays, Grandfather and Half-Brother or The Envoy, are devoid of any kind of sophisticated doctrine. These plays aim at the fatal double life, at the historical life lies of Switzerland and its neutrality policy, which came under fire in the public discussion in the nineties of the 20th century. Hürlimann settles accounts with the "second-hand agony of conscience" that Max Frisch attested to Switzerland as early as 1965, without any moral obligation to judge. Why the grandfather who protected the refugee posing as Hitler's half-brother during the war is insulted as a Nazi friend after the war, why the Swiss envoy who protected Switzerland with questionable moves in Berlin during the war (true to the motto that one does not rob one's own bank) is simply forgotten (and goes mad over it) after returning home from the war, the story finds no explanation for this. The opportunistic person likes to change his masks, not only in the theatre. Literature, at any rate, is there to unmask such lies. Its compulsory part is to "find again" such stories that have been lied away.

Political novels

Forty Roses is the name of Thomas Hürlimann's most recent novel to date. After the novella Fräulein Stark, it is his most successful. Around 100,000 copies have been sold, and there are already translations in two languages. At the same time, the novel is heading towards a major thematic mass of Hürlimann's prose already mentioned: time. If death is the narrator's birth, then the scarce time in which he is narrated is rich time, won lifetime.

Forty roses are delivered to Marie on every birthday, punctually at nine in the morning. They are a gift from her husband Max, who is aiming high in politics. His strange gift serves as a ritual to stop the ageing of love, to "play transience against the wall". Marie plays the role of the safe politician's wife too perfectly to let this charming deception burst. The rose queen in a Pucci dress, her cavalier in a dinner jacket, this is how the couple steers purposefully to the table of the political "Group One" in the Grand Hotel of the government capital. Here the man has finally made it - with and thanks to his clever, beautiful wife.

But again at the price of a family disaster. On his mother's birthday, the terminally ill son stays at home; the parents know he is going to die. The next stop of the flower messenger who delivers the magnificent bouquet in the morning is the cemetery. Time cannot be stopped or controlled, neither with punctuality nor with perfection - it trickles away inexorably because there is no one to ask for it. There is actually no such thing as the pure present, writes Augustine (in the tenth book of the Confessiones), only past and future, and in the mode of memory or expectation.

The present, which Hürlimann describes in his family trilogy, is one with the fashion of the social parquet and modern Swiss federal politics; and Marie and Max dance in unerring lockstep on both. Here, time lifts its mask. "Modérn", Karl Kraus knew, can also be read as "módern" by a slight shift in accent. "What is en mode today will be passé tomorrow," Hürlimann writes.

There is an important sign of the times in the novel. It is the Katz family coat of arms, which hangs over the house in the shape of open scissors. As Jewish emigrants, Marie's ancestors immigrated to Switzerland from Galicia. There, the "Seidenkatz" made it to fame and fortune in the ready-made clothing business. But the crossed blades that fit so well with Max, who owes his rise to cutting off old habits, also stand for the cancer that kills the son.

Where is the positive, one may ask here too? In the novel, it lies in music and love. They provide the connection with heaven that cannot be had on earth. The stories told by literature are also a remedy against transience. Even if they do not necessarily reconcile, they connect a narrative community that provides for the future of memory: the memory of family history, especially its Jewish branch, the history of Switzerland, the history of Europe and the Occident.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2011

Hartmut Lange

* 31 March 1937 in Berlin

The Art of the Novellist

If there is one author who has rehabilitated the genre of the novella, long declared dead in the post-war period, and breathed new life into it, it is Hartmut Lange. Away from fashionable trends, he has been writing - since 1980 - an impeccably clear, detailed prose schooled in Kleist. In this, his many years of experience as a playwright stand him in good stead. Born in Berlin in 1937, Lange began his literary career as a student of Hacks and a hopeful of the politically committed GDR theatre. But the lateral thinker, who resisted all ideological appropriation, had no luck either on the stages of the GDR, which he turned his back on in 1965, or in West German theatres. Now a handsome edition of Lange's Collected Novellas has been published. It presents the prose work, which has so far been available in twelve individual editions, in all its "story diversity", as the Giessen philosopher Odo Marquard unfolded it in 1998 in his laudatory speech at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation's literature award ceremony. Of particular note are the critically acclaimed novella Das Konzert (1986), a requiem for the Berlin victims of the extermination of the Jews, the Italian novellas (1998) and the most recent artists' novellas Die Bildungsreise (2000) and Das Streichquartett (2001).

Lange's heroes have everything they need: Money, education, a life - with or without a partner - according to their most beautiful ideas. But existential angst, the question of meaning, the insight into "being to death" (Marquard) always breaks into this pre-stabilised harmony. This realisation throws Lange's border crossers, who conspicuously often suffer from diseases of the walking apparatus, off their course and leads the novellas to a trenchant, surprising ending that, despite its modern content, cannot be called anything other than classical. The "unheard-of event" in Lange's novellas is always the intrusion of the mysterious into the world of the ordinary. They are abysmal and enigmatic stories of uncertainty and point out of our world "in which things only ever mean what they are".

The edition [Hartmut Lange, Gesammelte Novellen. In 2 volumes, Zurich: Diogenes, 2002 - editor's note] illuminates Hartmut Lange's major themes: the role of music, the disappearance of the subject, the rehabilitation of the metaphysical. And it fulfils all the prerequisites for making a recognised author into a well-known author at last.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2002

Burkhard Spinnen

* 28 December 1956 in Mönchengladbach

Hiob in Berlin - The novel Rückwind

How much fate can a person take? And how does one cope with bad news in times that swear by resilience, by resistance instead of religious instances? Burkhard Spinnen has constructed a remarkable epic experimental set-up. It is subtle in structure, intricate but not convoluted, highly suspenseful and with characters who act like clockwork: as "hand puppets from the material of the present", as Spinnen said during a talk about the novel in the Catholic University Community in Cologne.

Hartmut Trössner, the main character of Spinnen's novel, was born with a golden spoon in his mouth, so to speak. He has entrepreneurial spirit, perseverance, situational skills and luck. He becomes a manufacturer of wind turbines with a turnover of millions. And a successful television producer. His wife is a popular actress, his son well-bred in every way.

And then fate strikes. On a single day in April 2018, Trössner's company goes bankrupt, his son drowns in the swimming pool, his wife is killed in an accident, his house burns to the ground.Trössner, thoroughly suicidal, goes to a clinic and then takes the train to Berlin. This is where the actual narrative begins. And a first striking reading of the novel. Trössner is without doubt a modern Job, whom a lottery win hits "from behind". As improbable as this sounds in the concatenation of several misfortunes, such a thing is possible in principle.

Burkhard Spinnen places his character in the environment of modern media. And here begins a second reading. Trössner's wife has played the main role in a political television series that revolves around an extreme right-wing populist party, the "Party of Political Christians", or "PPC" for short: "Xenophobic, nationalistic, pithy slogans, achieves a double-digit election result", they say. Of course, this party is fictitious, but there are parallels to the fringes of the real existing political party landscape. Here lies the real trick of Spinnen's invention game. In the medium of the television series, which has the highest ratings and installs a novel within a novel, so to speak, there is a political occupation of religion - of a Christianity without a church, even without God.

In the name of the party programme of the "PPC", not only the occidental traditions of enlightenment and nationalism are cannibalised. The democratic rules of the game are also reversed in order to use them unconscionably against pluralism, tolerance thinking and cosmopolitanism. But Spinnen is not concerned with a political parable, but with politics in the medium. Does television make better politics? And possibly a more effective Christianity? What happens when the actors of political figures are not only mistaken for their models, but slip into the roles of those they portray themselves? It is the Job-like hero himself who confronts these questions by going to the filming location of the series, Berlin. The ending is too furious to be given away here. It takes place in the Ministry of Finance and fulfils all the criteria of a good "Tatort" thriller.

All this is unobtrusively and artfully composed. A brilliant novel, frighteningly realistic, told with discreet irony and astute diagnosis of the times, a book precisely for and about our times.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2019

Louis Begley

* 6 October 1933 in Stryj

On the search for a good life

Literature has inherited the idea of a happy life from philosophy. But only a few authors today dare to seriously tackle the Atlas-heavy task of telling stories about it. Louis Begley, too, distrusts big feelings and happy endings. His novels deal with the catastrophes of happiness, with family disasters, illness, death, betrayal of love, loss of memory and hope.

Biography and work

Louis Begley has written nine novels, the first in 1991, at the age of 68, the autobiographical novel Wartime lies (1991; Lügen in Zeiten des Krieges, 1994). The tenth novel will be published in German translation by Suhrkamp in autumn, just in time for the author's 80th birthday: "Erinnerungen an eine Ehe". Here, too, Louis Begley expands his range of themes with aplomb. It is about obstacles to marriage and matters of honour, about morality and professional success, about the wishful unhappiness of better society - quite in the style of Ingmar Bergmann's film "Scenes from a Marriage". The narrator is not a writer by chance. Not without a highly likeable self-irony, he describes his hardships in getting from facts to fictions. He wants to research for a novel without distorting the truth, but has to add a lot to what he knows and remembers in order to create an exciting story.

Louis Begley's own life story provides the material from which his novels spring, but it is also fiction in the sense of the title of his life-smart Kafka book The Monstrous World I Have in My Head (2008). Louis Begley was born under the name Ludwik Begleiter as the only child of Polish-Jewish parents on 6 October 1933 in the East Galician provincial town of Stryj, which was Polish between the world wars and today belongs to Ukraine. In the summer of 1941, German troops occupied the country, which had been evacuated by the Red Army. In the shadow of the Wehrmacht, the extermination troops of the security police moved in. Louis Begley fled with his mother, disguised as Polish Catholics.

When the war ended, Louis Begley emigrated to the United States with his parents in early March 1947. In New York, he anglicised his name, began studying law at Harvard and became a successful lawyer at the law firm "Debevoise & Plimpton" on Wall Street.

Begley became a writer in 1989 when he retired from the firm for four months to write his first book. Wartime lies is not a life confession, but a novel of recollection that condenses and transforms his own experiences. The lies in times of war, which the young novel hero Maciek uses together with his aunt Tania, ensure their survival in hostile surroundings and at the same time show the power of memory fiction. "I tried, in the voice of the observant Maciek, to translate layer by layer total inhumanity, horror, horror into language with a constant narrative tone," Begley said in an interview with the Jüdische Allgemeine Wochenzeitung in 1994.

After his novel debut, he wrote a series of philosophical novels, about which Christoph Stölzl said on the occasion of the awarding of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation Literature Prize to Louis Begley: "Begley's suite of transatlantic social novels, written in a short decade, will probably one day be read as detached from their time of origin as Fontane's Berlin cycles or Thomas Mann's modern Odyssey of the bourgeoisie."

Begley's characters are middling heroes, uncomplaining Job figures, Kafkaesque bankers and brokers, lawyers and authors; these characters are not unsympathetic, whose track records regularly fail when it comes to their own affairs of the heart. "Shipwreck", Begley's 2003 novel title, is their fate, remembering an amour fou their programme, stoic renunciation their conclusion.

Ben is perhaps the most representative of these heroes - alongside the philosophising pensioner Schmidt, who was also filmed with Jack Nicholsen and to whom two wonderful novels (published in 1996 and 2001 in German translation) are dedicated. Ben plays the main role in Begley's second novel, The Man Who Was Late (1992). He is a "Jewish refugee" who wants to learn the good life in America, but gets tangled up in the contradictions between self-hatred and the desire for happiness. He is certainly happy in the world of "cashless well-being", especially with women. But he cannot be happy with it.

At the centre of Begley's literary work is the question of the future of humanistic values. What happens when personal "notions of the good and the humane" are thwarted by intrigue, manipulation and prejudice is what he explored in a book about the "Dreyfus case" (2009). Tellingly and warningly enough, it bears the subtitle "Devil's Island, Guantanamo, History's Nightmare". The good life is not a gift, after all. It has to be told, through the catastrophe, which literally means a change of luck. The new novel gives us hope that the author will not stop telling stories about the search for happiness even in his ninth decade of life.

Author: Michael Braun

State: 2013

Norbert Gstrein

* 3 June 1961 in Mils near Imst

Aeronauts, aeronauts, high-flyers

Airmen in literature are traditionally sad or comic heroes. Threatened by a crash, at the mercy of the elements, they hang between heaven and earth, and only rarely manage to escape the fate of Icarus, on whom the myth inflicts divine punishment for hubris and megalomania. The fall of Icarus or Euphorion also symbolises the failure of the artist who aims too high with his work. In addition to this tragic history of motifs, there is an initially narrow, but with the triumph of the natural sciences visibly stronger tradition in which aeronautical projects function as material for adventure stories and provide important motifs above all for the utopian novel literature of the 19th century. After a technophile phase of literary history at the beginning of the 20th century, inspired by popular air shows and culminating in Gabriele d'Annunzio's aeronautical novel Forse che sí forse che no (1910), a "transformation" of the utopian novel occurs. In science fiction literature, space travellers have taken the place of airmen, the stratosphere is terra cognita, and what were once challenges for aviation pioneers have become routines for low-cost and frequent flyers in the 70 or so years between the Wright brothers' stuttering attempts at flight in Kitty Hawk (1903) and the first commercial Concorde flight (1976).

It is all the more surprising that Norbert Gstrein revived the balloonist material in 1993 with his novella O2 and was successful with both the public and critics. The theme returns to a post-Utopian media world that makes everything seem feasible. The historical event, the 1931 balloon ascent into the stratosphere, is mirrored in the diverse - fictitiously embellished - reactions of those involved in the air and on earth. In this way, the novella is an epic lesson on the relationship between fact and fiction. It demonstrates the question of who owns a story - the media, the historians, the poets - and what they make of it.

Stories and counter-stories

Distortion and falsification of a story through the perspectives of counter-stories has been a theme of Gstrein's narrative works from the very beginning. The motto of Thomas Bernhard, which stands above Gstrein's first novel Das Register (1992), points to the origin of this theme: "How many of our talents could we have developed to astonishing greatness within us if we had not been born and grown up in Tyrol". Tyrol and the Alps, village narrowness and the destructive effect of mass tourism are the coordinates of Gstrein's first books. But there is more to discover than the negative Heimat novel and the anti-idyll. Gstrein's debut novel Einer (One, 1988), about the life of an innkeeper's son on the fringes of village society, develops the pathography of a personality destruction. Jakob is "Einer", who is always the whipping boy, unloved child, abused boarding school pupil, inhibited lover, mocked ski instructor and finally apathetic drunkard, a stranger even in his own parental home, where his story is reconstructed from the perspectives of changing characters. The mystery remains: Jakob is picked up by an inspector, "after a misdeed or mishap committed" (E 113).

Loss of identity due to social constraints, however, is only one level of the narrative. The true misery of the soul, of which Gstrein's narratives are saturated as if by a hospital smell, is reflected in the language distress of his characters. "Language lacked words" (A 32) is the programmatic title of the story Anderntags (1989), which is about unhappy self-discovery and gradual silencing. The thirty-year-old first-person narrator Georg tries to come to terms with the love affair with his girlfriend who died in an accident. But the "misunderstandings in speech" inevitably lead to a "growing brutality [...] - also in language" (A 96ff.). Jorge Semprún, Norbert Gstrein's laudator at the award ceremony of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Weimar, has precisely described how this language of Gstrein's

"destroys the conventional idioms and routines of language in order to present everything that seemed doomed to silence - that is, to loss and disappearance - in the fabulous light of the uttered, even if it remains, possibly, an ambiguous, even ambivalent light".

Stories from the Austrian 'Province'

The novel Das Register marks a decisive step towards the theme of O2. Once again, the leitmotifs of the previous stories appear: the failure to be Austrian, disgust with the world and oneself, loss of identity and linguistic distress; once again, the plot takes us to the valley worlds of South Tyrol, where "generations lived on the same spot, never leaving the village" (A 13), where on Sundays "the clatter of the tourist fakers hurt deep in the stomach" (A 52). But Gstrein distances himself - more clearly than before - from clichéd tourism criticism and larmoyant Austria-bashing. In keeping with the poetics of the novel, he presents a larger section of the world, expanded historical contexts and psychologically differentiated characters. The story is told in the style of a Tyrolean family chronicle about a pair of unequal brothers who set out into the world to seek "success at any or almost any price" (R 125) in skiing or to bury themselves in the biographies of famous mathematicians. It is not difficult to discern data from Gstrein's own family history behind this. His brother is a successful skier, he himself studied mathematics at Stanford, Erlangen and Innsbruck.

The Register is undoubtedly Gstrein's most autobiographical book, "a kind of fictional autobiography", as the author himself says. The title alludes to the father's habit of keeping meticulous records of all expenses "since birth", to which the self-tormenting question is attached: "Were we worth so much?" (R 83) By coming to terms with a father complex, the novel advances to a "sociology of provincial life" and to a "determination of the essence of the Austrian mentality", the core of which is a patriarchal pattern that manifests itself in the country's political history. Compared to the grandfather, one of those nouveau riche "tourism pioneers", the father, a disgraced teacher, is only a "domesticated, degenerate offspring" (R 62).

"Prehistories": Balloon Rides in Literature

There is definitely method in the way O2 literally rises from the familiar ambience of contemporary Austrian literature and gives shape in the form of the balloon to the hope mentioned in Gstrein's previous works, "to go on, beyond all borders" (R 17). The balloon in which Piccard set off on 27 May 1931 on his "legendary stratospheric flight", later recounted in the "report" Der Kommerzialrat (1995) in the style of "peasant kitsch and lie literature" (O 74f.), is a symbol of the distancing from the "classical" theme of Austria.

Piccard's balloon trip has a prehistory that plays along as a recursive, intertextual element "because every story had a prehistory, and every prehistory had a prehistory again, again and again" (O 22). On the one hand, it is presented as a "chronique scandaleuse surrounding the legendary stratospheric flight of the Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard [...]" (K 53) in Gstrein's Kommerzialrat, where it is faked as the boastful autobiography of the elementary school teacher Schatz, who in turn has appeared as a perspective figure in O2 - a significant catching-up intertextual self-reference.

On the other hand, this prehistory - if one disregards the experiments of Leonardo da Vinci, who in 1513 in Rome made hot-air-filled figures of saints rise into the sky, and Francesco Count Lana di Terzis, who invented a vacuum airship in 1670 - already begins on 5 June 1783 in Annonay with the first public (still unmanned) balloon ascent by the brothers Jacques-Etienne and Joseph-Michel Montgolfier, followed only a few months later by Jacques Alexandre César Charles' hydrogen balloon in Paris. The reactions to the world sensation ranged "from the deepest reverence for the achievements of the discoverers to dripping mockery of the after-effects, from religious doubts to euphoric expectations of the future" and also took hold of Goethe, who was not only interested in the scientific-technical aspects of the balloon flights in France and in German cities and took part in experiments himself, but also gained an aesthetic side from them: as a parable for the greatness and limit of artistry:

"Whoever witnessed the discovery of the air balloons will bear witness to the world movement that arose from it, the share that accompanied the airmen, the longing that arose in so many thousands of minds to take part in such long foreseen, predicted, always believed and always incredible, perilous wanderings [...]."

Ballooning as fiction

The flight, the preparations, the preliminary tests and the evaluation of the results, which Piccard described in his memoirs Between Earth and Sky (1946) and Above the Clouds, Beneath the Waves (1954) in the dry jargon of the specialist scientist, provide the framework of Gstrein's novella. He is not concerned with documentary reproduction of assured data and facts, but with "how a new kind of reality is constructed in the telling" (W 10). An indication of the fictionalisation of the material is the omission of Piccard's name, who is usually titled "Professor" (15, 18, passim). A curriculum vitae multiplied by the press introduces him:

"Born in Basel, he studied at the ETH Zurich and was a private lecturer and professor there, before his appointment to Brussels. The deciding factor in accepting it was not only that he became director of the Institute of Physics, but above all the assurance of an unrestricted budget. [...]. Before that, he had himself undertaken the first balloon flights, as a member of the Swiss Aeroclub, and was in the process of making a name for himself in aviation circles, not least with his much acclaimed lectures 'The Stability of Aircraft' and 'Theory of High Altitude Flights and Maximum Speeds'" (O 22f.).

The flight, which began early in the morning in Augsburg, lasted 17 hours and ended around 9 p.m. on a "rounded glacier" on the Gurglferner in Tyrol, is described in Gstrein's novella as a chain of mishaps, as a "'story of many misunderstandings'" (O 19f. ), from the "leak" (O 14) in the cabin wall, to the blocked valve line (O 33), the shortage of oxygen (O 59) and the constant checking of the pressure balance, to the near-accidental landing. In addition to the technical details, the descriptions of nature are particularly striking, such as the flight over an Alpine relief:

"chains of peaks spread out below us in all directions, it was a real sea, snow-covered or without snow, in the most rugged, forbidding places, a sight indeed to hold one's breath, and there were no words that could do it justice" (O 114f.).