Issue: 3/2018

IR:Professor Reckwitz, your book “The Society of Singularities” paints the picture of a society that is downright obsessed with the extraordinary: unusual hobbies, individual eating habits, highly styled apartments, and customised adventure holidays – maximum self-realisation appears to be the only measure of a “good” life. Is there no room left in our society for that which is general and binding?

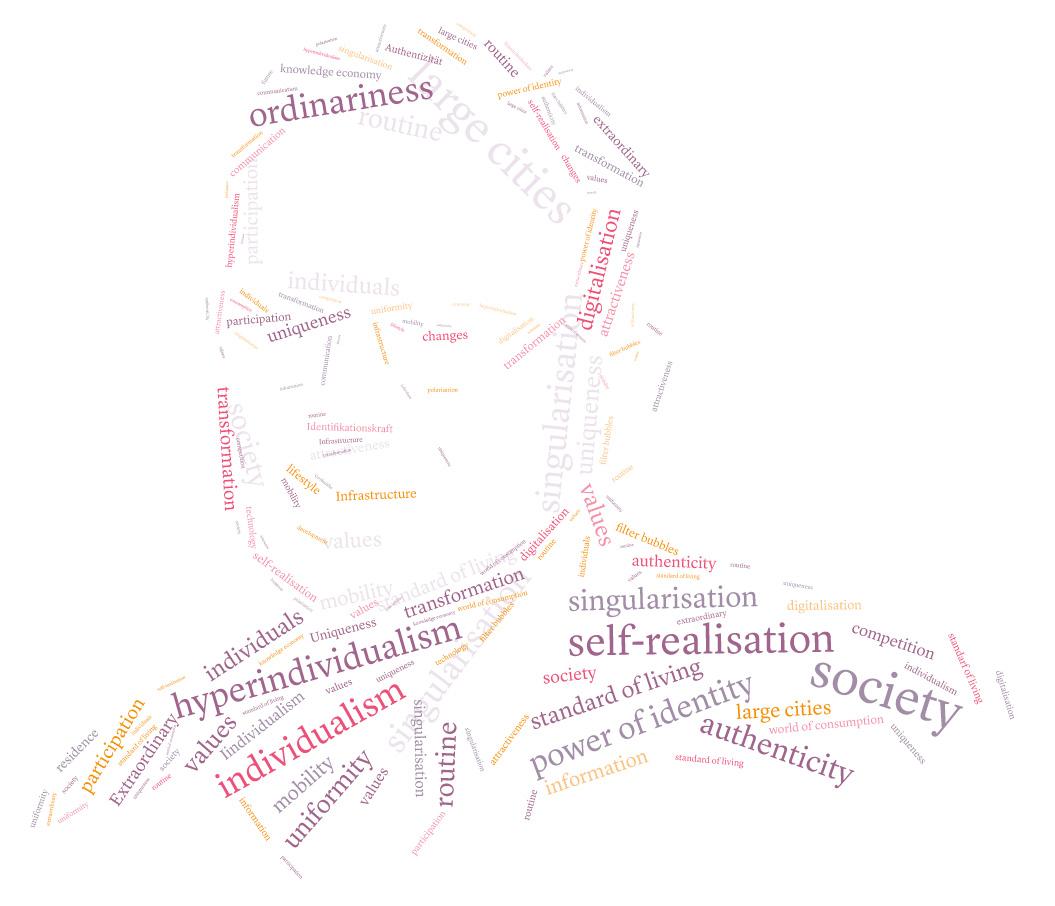

Andreas Reckwitz: I do not want to sink into generalised pessimism about culture. But my book does in fact carefully examine the social mechanisms through which these processes of singularisation, that is, of orientation on that which is unusual and unique, have spread in Western societies over the last few decades. What is at work here goes beyond mere individualism. It is not just individuals who are trying to be special and non-interchangeable – which becomes especially obvious in digital media like Instagram and Facebook –, things and objects, such as the goods of cultural capitalism from the individual piece of craftsmanship to the Netflix series, are also to be experienced as unique.

IR: So interpreting it as hyperindividualism would fail to go far enough?

Andreas Reckwitz: Most certainly, since even spatial units such as cities are engaging in global competition by attempting to design themselves as units with special urban landscapes, special atmospheres. Or take the singularisation of temporal units: the trend is away from routines and toward events, special moments, or projects. Ultimately, we are seeing the paradoxical profiling of collective units as special in the wake of the “Society of Singularities”. One conspicuous example are “imagined communities” such as regionalistic movements extending from Catalonia to Scotland: one's own people with its special history is also singularised here; this enables the power of identity to unfold. Thus, singularisation goes far beyond the “individualism” of individuals.

IR: So, “Be special!” is, in a sense, the imperative that provides orientation not only to everyone, but also to everything?

Andreas Reckwitz: Yes, but it is important to see that the orien-tation towards the unusual and unique is itself a thoroughly societal process in which entities are assessed, produced, and experienced as being unique. Almost everything in late modern society that promises identification and emotional fulfilment takes the form of the singular – from holiday trips to attractive jobs, romantic relationships, and desirable places to live through to political projects. Overall, this is shifting the primary societal evaluation criteria: whereas during the period of the classical industrial society from the 1950s to the 1970s, dominant criteria included the normal and the standardised: the same standard of living, the same types of residence, major political parties, mass culture, etc. These criteria have increasingly shifted towards the unusual. This is because singularity promises authenticity and attractiveness. These are the primary values of the late modern period. What society therefore deems to be weak and of little emotional appeal is ordinariness, routine, and uniformity.

IR: A society does not make fundamental changes for no reason at all. What do you think are the causes of the development you have described?

Andreas Reckwitz: I identify three sets of causes in particular: economic, cultural, and technological. The economic one refers to the goods that promise cultural value and uniqueness, the area of growth of late modern economy – be it tourism or the internet industry, education or nutrition. The classical industrial economy reached its limits back in the 1970s and is being increasingly displaced by a cognitive, cultural, or immaterial capitalism. What is successful here is what marks a difference, what promises a special experience or identificational potency. It is therefore no wonder that only about 20 per cent of workers are employed in industry – it used to be 50 per cent. The spearhead of this development, however, is the so-called knowledge economy. But singularisation is not merely the result of economic competition. A cultural factor is also of importance: what late modern individuals want for their lives is not the standard, but the singular. They are influenced by a life principle of successful self-realisation, and individual development in a multitude of opportunities. This is the result of a far-reaching shift in values, which have been underway since the 1970s: away from duty and acceptance values toward self-realisation values. Of course, there is a long tradition behind this shift, but it was not until the development of a broad new middle class, most of whom had high levels of education and participated in the knowledge economy, that a lifestyle of successful self-realisation found a substantial social group to support it and thus became culturally dominant for the first time. Finally, there are also technical framework conditions for singularisation: digitalisation. The internet’s algorithms ultimately create an individualised world of consumption and information that is identical to no other such world, addressing each person in his or her uniqueness via data tracking. Additionally, the internet also generates a massive selection of images and texts that are compliant with the radical laws of the attention economy. In this economy, the only way to succeed, whether that be a YouTube video or Instagram photo, is not to be like everything else, but to have an interesting difference to attract attention through singularity.

IR: If you look at what things succeed on platforms like Instagram and Facebook, you see the new designer tennis shoes, dinner from a popular sushi place, or a selfie with someone who is more or less a celebrity – all of them things that you would associate with trendy neighbourhoods like Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin and not so much with Kirchberg an der Iller or any other little village in the countryside. Is the “Society of Singularities” primarily a big-city phenomenon?

Andreas Reckwitz: Yes and no. On the one hand, singularisations exist independently of the city-countryside question. Everyone participates in the internet, and it allows the promises of cultural capitalism to penetrate into even the remotest of villages. On the other hand, big cities are in fact the places where the Society of Singularities concentrates – which is not surprising, since cities have always been at the cutting edge of new developments throughout modern history. There are also reasons for that in this case: as I said, the supporting group is the new middle class, the highly qualified, and they congregate in large cities, if for no other reason than that this is where they can study and get jobs in the knowledge economy. At the same time, of course, big cities offer an especially wide range of opportunities for singular goods in the broadest sense: opportunities for high and scene culture, widely varied choice of schools for children, gastronomy of various types, exercise classes from Tai Chi to tango, and so on and so on. The influence of global culture is especially great in the big “cosmopolitan” cities.

IR: But can’t a village also be a place of self-realisation?

Andreas Reckwitz: Sure, and that is an idea that is as current as it is old. Around 1900, a life reform movement fed the longing of big-city-dwellers for a return to the countryside. Today, there are also tendencies among city dwellers to acquire a second property in the countryside or even to migrate completely – from Berlin to the Brandenburg countryside, for instance. People expect to find something that they do not get in the city: nature and peace, preferably in “unique” surroundings. However, a new flight from the cities seems to be constrained by practical limits for the time being: the highly qualified professions in the knowledge economy concentrate in cities.

IR: So there is competition not primarily between city and countryside, but more among the cities themselves?

Andreas Reckwitz: In fact, industrial cities were relatively interchangeable in industrial society. In post-industrial society, on the other hand, cities polish their profiles so as to be unique: that applies to Hamburg or the Ruhr, Marseille or Copenhagen. That is not merely a question of city marketing, but of structural design of the cities themselves. Why do they do it? The reason is primarily the significance of the new, educated middle class and its great spatial mobility, including the workplace mobility of highly qualified individuals. The cities find themselves in competition in order to appeal to inhabitants, visitors, and companies. The ones that succeed are those that can offer the right quality of life, those that successfully develop a “self-logic”, as Martina Löw put it in “Sociology of Cities”. In the late modern era, we are therefore experiencing polarisation at the spatial level as well: between boom towns and abandoned regions. The boom towns are beginning to suffer the consequences of their success as singular locations, however: overcrowding, congestion, high rental prices, etc.

IR: You already mentioned Hamburg, the Ruhr, Marseille, and Copenhagen. Does that mean that the phenomenon of singularisation is primarily a European or Western one?

Andreas Reckwitz:Yes and no. Transformation due to singularisation does indeed initially centre on Western societies. They were the first industrial societies and are the first post-industrial societies. They therefore experience especially intense competition among their cities. But the rapid social changes in several emerging countries are clearly beginning to exhibit singularisation processes. Consider metropolises like Shanghai, Singapore, and the cities of the United Arab Emirates.

IR: So singularisation is becoming noticeable in Asia, even though the collective group traditionally enjoys a much higher value there?

Andreas Reckwitz: That is an important question, and it would require a separate study to answer it. There is a long tradition of distinguishing Western individualism and Eastern Asian collectivism, but you have to be careful not to think of them as closed cultural circuits, like adjacent spheres with no mutual influence. Cultural capitalism and the digital attention economy exert massive influence in places like Japan, South Korea, and the Chinese metropolises. They will probably result in a mixture of singularism and elements of these cultures’ collectivist heritage.

IR: The phenomenon of singularisation also has another dimension: self-realisation is, after all, not necessarily what social cohesion is based on, and even if some people may be disdainful of such things as church on Sunday, fire brigade festivals, and neighbourly cooperation, these practical social measures play important societal roles. My question is therefore: what price does a society pay for increasingly allowing these things to die out?

Andreas Reckwitz: The Society of Singularities is indeed to be observed with ambivalence. It has advantages, and it has costs. Life according to the criteria of successful self-realisation provides great opportunities for individual fulfilment and quality of life – more than in the classical industrial society. But there are winners and losers, and there are societal structures that are forced into the defensive. Industrial society had distributed social recognition relatively evenly: almost everyone was in the middle class. In the post-industrial society, polarisation set in: expanding education allowed the rise of the ambitious, urban new middle class. But another group are on the decline: the new underclass of low-qualified people, often employed in providing simple services, or outside the labour market altogether. Between the two is the old middle class, which feels itself to be at least somewhat on the cultural defensive and tends to champion the lifestyle typical of the old industrial society. “Being left behind” takes on various forms. In these three groups, people live in completely different worlds. The groups have diametrically opposed feelings for life. Those involved in public politics need to deal with these differences, but are themselves in crisis: digitalisation is dissolving what has been the “general public” that still had fixed points of reference such as the daily paper and the television that everybody used. Political communication is itself being singularised online. The notorious filter bubbles are forming.

IR: You describe the major parties in this context as “stewards of the commons” who almost inevitably experience crises in a “Society of Singularities”. Are major parties relics of the past?

Andreas Reckwitz: The major parties were characteristic of the “dominion of the commons” in industrial society. In a society that is quite homogeneous in any case, they were able to combine the interests of various milieus. Indeed, since the 1980s, a shift in political structures has accompanied the societal shift. One dimension is the singularisation of the party system. If you look at Scandinavia, the Netherlands, or more recently at France, this becomes especially clear: a number of new parties have arisen to address more closely networked milieus, but they develop a great identity-forming character. The major parties – the conservatives and the social democrats – lose when that happens.

IR: If you were a consultant for a major party, what strategy would you recommend? Enhancing the core brand and focusing on the base? Ultimately, one could also argue that a “Society of Singularities” is especially dependent on political forces that focus on what is common and what binds society together.

Andreas Reckwitz: There are two possibilities for such a singularised party system: either there is polarisation in which everybody insists on their own unique selling point, or a new culture of compromise arises among the many small segments of the party. In the latter case, it matters little whether these compromises are reached within a single large party (the major party model) or among many small parties. You cannot simply advise the major parties to concentrate on their voter base. The fact that these bases are eroding is the very cause of the problem.

Generally, however, late modern politics in particular faces the question of a renaissance of commonality: society – business, technology, lifestyles – is singularising rapidly, but shouldn’t politics compensate for that development by creating common and generally applicable framework conditions? This affects the “cultural question” as well as the “social question”: the question of securing infrastructures, participation in social goods, and education for everyone, of securing basic standards and a generally observed level of civility on the internet. The question of what form a general policy should take as part of a Society of Singularities is the central question of the politics of the future.

The interview was conducted by Sebastian Enskat.

– translated from German –

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.