Issue: 3/2018

American society is becoming increasingly polarised in many domains: Democrats versus Republicans; a portion of the middle class versus the establishment; and globalisation supporters versus globalisation opponents. However, these various dimensions of polarisation are not always identical and cannot be summarised by means of a simple left-right opposition. There are globalisation opponents on both sides of the political spectrum and in all classes of society, for instance. What all these forms of polarisation have in common, however, is the increasing degree of irreconcilability with which the respective groups confront one another.

The American public’s awareness of one dimension of this polarisation has increased since the last presidential election, even though it has affected the country for decades: the growing political divide between urban and rural areas. Experts have noted that, since 2008 in particular, the correlation between population density and voting behaviour in the US has risen. US cities are becoming bluer (blue is the official colour of the Democratic Party) while much of the non-urban space is becoming redder (red is the official colour of the Republican Party, or the GOP – the Grand Old Party). This phenomenon is especially marked at the extremes – in the large cities and in the most rural areas of the US. In the last decade, a political chasm has opened up between urban and rural populations.

In the 2016 presidential election, this urban-rural divide was especially noticeable: Large American cities overwhelmingly supported the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, while Donald Trump and the Republicans gained votes everywhere else in the country. The Republican candidate was particularly popular in small towns and rural areas: the more rural the constituency, the stronger the support for the unconventional politician (see fig. 1). This political divide goes beyond electoral preferences: A recent study by the Pew Research Center shows that in rural areas and in the largest metropolises alike, the majority of Americans think that people in rural and urban areas have different values. In addition to outright disagreements on controversial issues, such as immigration, same-sex marriage, and the role of the US government, each group believes that the other fails to understand their problems and condemns them.

The divide between urban centres and their peripheries constitutes the core of this article. The aim is to map out the socio-economic characteristics of the urban-rural divide in the US in order to then analyse the resulting current political consequences. Doing so raises the following questions: What political conclusions can be drawn from this situation? What challenges are Republicans and Democrats facing in the next election because of this urban-rural divide? And a final important question: What can be done to bridge this divide?

Fig. 1: Votes in the Presidential Election 2016 (in Per Cent by Population Area)

I. The Urban-Rural Divide

The US Office of Management and Budget (OMB) distinguishes between metro counties – urban counties in or in the immediate vicinity of large cities of at least 50,000 people –, and non-metro counties – counties that encompass both small towns outside of major concentrations of people (2,500 to 20,000 people) and rural regions. According to the Department of Agriculture, 85 per cent of Americans live in urban centres (metro counties, which will be referred to here as “urban”) and 15 per cent in the countryside.

People tend to have the same concerns about rental prices, poverty, and the availability of jobs, whether they are in large conurbations or in rural regions. There are nevertheless significant economic and social differences between urban and rural areas.

Economic Challenges in Rural Areas

The rural-urban discrepancy is particularly striking on the labour market: As in other Western countries, jobs have been disappearing from rural America in the agricultural and manufacturing industries for decades. This is due to both process automation and increasing competition worldwide. However, the development of the service sector and of new technologies is creating new jobs in the conurbations. This is where most qualified people live (low-skilled positions in the service sector, such as call centres, tend to be outsourced to foreign providers). Until the mid-1990s, one third of all new companies were founded in the most rural counties in the US; this has long ceased to be the case. The economic recession of 2008/2009 exacerbated the situation further: The rural labour market shrank by 4.26 per cent between 2008 and 2015; yet, despite sinking until 2013, the urban labour market grew by 4.02 per cent. Since 2013, the creation of new jobs in rural regions has continued, but, as Steven Beda of the University of Oregon emphasises, those jobs are not in traditional sectors, but in the service industry: “So Appalachian coal miners and Northwest loggers are now stocking shelves at the local Walmart.”

Average annual income has fallen slightly across the country since 2000 due to the financial and economic crisis. However, people who work in rural regions still earn almost 30 per cent less than their compatriots in big cities (35,171 compared to 49,515 US dollars annual income). According to Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley, this gap is now 50 per cent greater than it was in the 1970s. Poverty levels in rural regions are comparable to those in cities (18 per cent against 17 per cent). Nevertheless, 31 per cent of rural counties compared to only 19 per cent of large cities face “concentrated poverty” (at least one fifth of the population below the poverty line). In addition, following the real estate market collapse, prices in rural areas have risen more slowly than prices in cities, which has eroded the financial capital of many households on the periphery. In light of these reasons, for many Americans on the periphery, the economic crisis has not been overcome yet, while city dwellers can already look to the future with greater confidence.

No Country for Young Men

Given these economic characteristics, it is not surprising that the rural population has a different demographic profile to that of the urban population. For one thing, it is older: Since 2000, 88 per cent of rural counties have seen people of working age (25 to 54 years old) move away. The average age in small towns is now 41 – five years above the median in large cities. The rural population is generally less well-educated, even though the overall share of Americans with an academic degree has risen since the year 2000. For instance, there are more people in cities with a bachelor’s degree than those holding merely a high-school diploma. This relationship is reversed in rural areas. Moreover, 11.8 per cent of the inhabitants of large cities (defined as communities of 50,000 or more) suffer from disability. In small towns (between 10,000 and 50,000 inhabitants), the rate is 15.6 per cent, and in the most rural areas, it rises up to 17.7 per cent.

As in other Western countries, the strained economic situation and demographic development have led to the decline of rural areas. In small towns, there are fewer and fewer retailers and service providers, such as post offices, child care centres, and schools. This can have dramatic consequences, especially in the healthcare sector, for example, when those who are ill are forced to travel long journeys to the nearest doctor, or even experience difficulty in getting an appointment at all. According to the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, 79 hospitals in rural counties closed between 2010 and 2017. This situation is particularly challenging in the context of the opioid crisis, which is more pronounced in small rural communities than in large cities. Between 1999 and 2015, the mortality rate caused by opioids in rural areas quadrupled among 18 to 25 year olds and tripled among women. A University of Michigan study showed that between 2003 and 2013, the number of newborns with opioid withdrawal symptoms in rural communities grew 80 times faster than in cities.

While large American cities in the 1980s and 1990s were notorious for their lack of security, high crime rates, and socio-economic problems, the situation today is quite different. The city centres of most US conurbations are becoming increasingly attractive for companies and employees. The process of gentrification is causing rapid rises in real estate prices and is changing the cityscape due to increasing demand for public infrastructure, such as tram lines and cycle paths. On the other hand, the situation in rural areas today is worse than in the rest of the country in many respects, including: average age; level of education; employment rates among working-age men; disability rates; teenage pregnancies; divorce rates; and a number of medical complaints, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and chronic pulmonary diseases.Interestingly, there is a strong consensus among Americans that government funds are not being apportioned fairly, with too little being allocated to rural areas.

Fig. 2: Voters Preferences (in Per Cent)

II. Political Wake-Up Call

It was only the result of the 2016 presidential election and the surprising defeat of mainstream candidate, Hillary Clinton, that brought to light the political dimension of the urban-rural divide in its entirety.

Changing Moods in Rural Voting Districts

The statistics of the last 20 years show that the majority of urban dwellers have consistently favoured the Democrats, in ever great proportions (55 per cent in 1998, 62 per cent in 2017, see fig. 2). In rural districts, on the other hand, support for the GOP has grown, especially since 2008, so that it now enjoys a majority (44 per cent in 1998, 45 per cent in 2008, 54 per cent in 2017).

Bill Clinton was the last Democratic candidate to win a majority of voters in both urban and rural areas: In both 1992 and 1996, he won almost half of the 3,100 counties in the US. Since then, the Democrats have been successful primarily in cities. In 2000, Al Gore, won the popular vote, although he won fewer than 700 counties. Barack Obama won 86 of the 100 most populous counties in the country in 2012, which was decisive for his victory, since he won only around 600 of the remaining 3,000 counties.Hillary Clinton’s defeat was the result of a combination of two weaknesses: Her support in key urban areas was significantly weaker than Obama’s in 2012, such as in Detroit or Philadelphia, and she lost even more votes outside the largest urban areas than the last Democratic president did (see fig. 3).

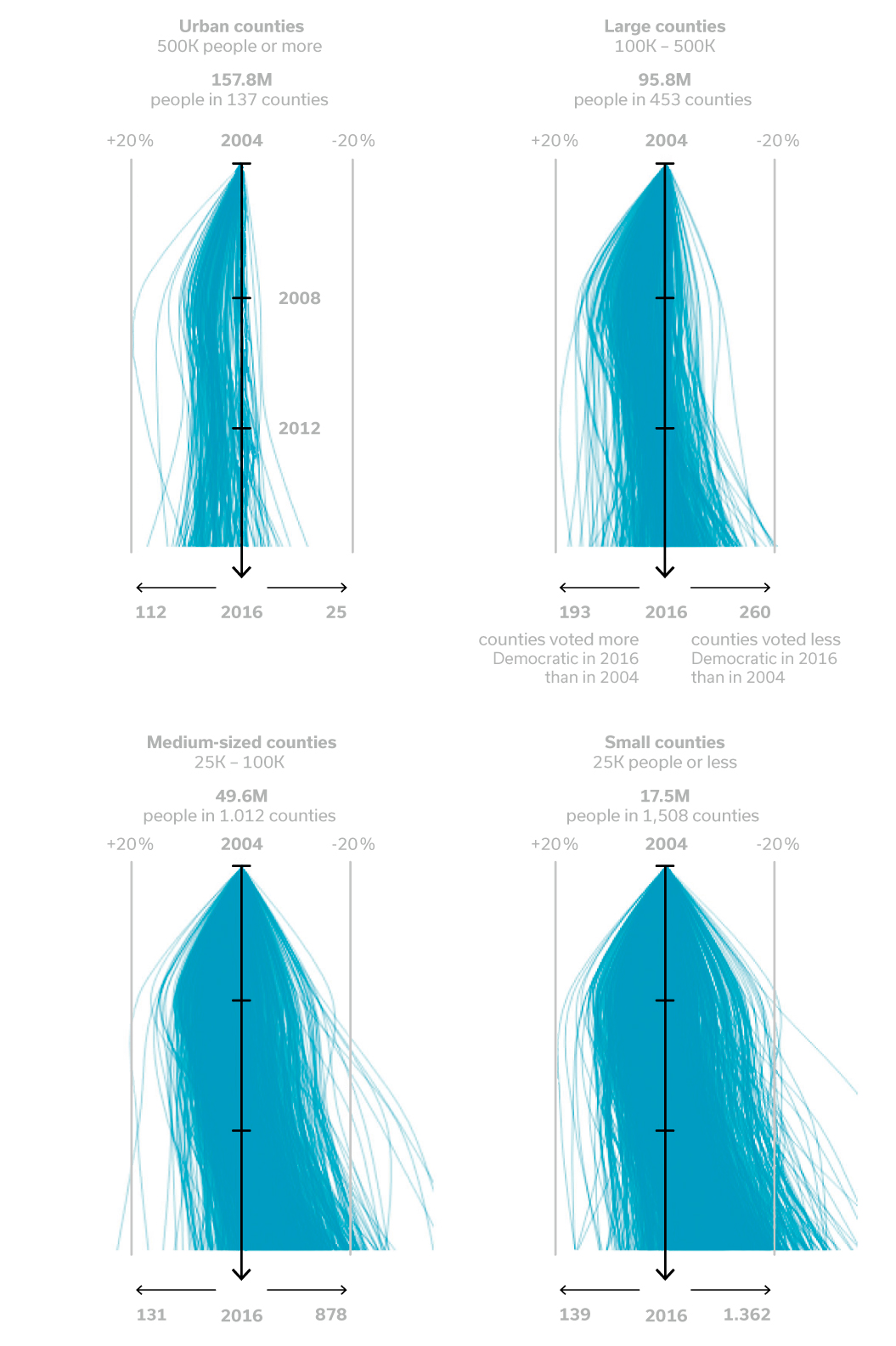

This growing polarisation is most noticeable in the largest urban areas (500,000 inhabitants or more) and in the most rural ones (25,000 or fewer). The Democratic Party fared better in 2016 in 112 of the 137 most populous counties (where a total of 157.8 million Americans live) than it did in 2004; at the other end of the geographical spectrum, the share of votes that went to the Democratic Party decreased in 1,362 of the 1,508 most rural counties in the country (with a total of 17.5 million inhabitants) in the same period (see fig. 4).

A key factor in the 2016 presidential elections, however, were the medium-sized counties, i. e. districts, suburbs and small to medium-sized cities with between 25,000 to 100,000 inhabitants – where a total of almost 50 million Americans live. While they had strongly supported the Democrats in 2008, eight years later they voted overwhelmingly for the Republicans (see fig. 4). This development was a decisive factor in Donald Trump’s victory in the so-called swing states of the Midwest. For instance, 68 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties gave the Democrats less support in 2016 than they did in 2004 (see fig. 5). In the 2008 and 2012 elections, the majority of these counties still opted for the Democratic candidate. This shift in 2016 primarily affected small and medium-sized counties (marked by thin red lines in fig. 5). However, large suburban counties, such as Racine and Kenosha (between Milwaukee and Chicago) have also changed sides politically. Urban counties such as Dane (which includes Madison, the capital) and Milwaukee have remained loyal to the Democrats throughout.

Fig. 3: Difference in Support for Democratic, Republican and Independent Presidential Candidates in 2016 versus 2012 (in Percentage Points)

The American presidential election system, which favours rural states, was an important factor in Donald Trump’s triumph, which occurred despite the opposition of most city-dwellers. The conflict between urban or populous states and rural states was already at the centre of a Constitutional compromise at the founding of the American Republic. It was determined at the time that rural states would always have two senators, even if their population only gave them the right to one seat in the House of Representatives. This leads to very different voting weights from state to state. Rural states are also overrepresented during presidential elections: Due to the distribution of Electoral College votes, a vote in Wyoming, a very agrarian state, has four times the weight of one in the state of New York, for instance.

Fig. 4: Evolution of the Democratic Vote in Every County Since 2004

Fig. 5: Evolution of the Democratic Vote in Wisconsin Since 2004

Resentment as a Driver of Polarisation

The reasons for the growing urban-rural divide are complex. According to surveys, politically conservative individuals traditionally prefer to live in large houses in small towns or rural areas, among those with similar religious views, while Democrats generally prefer apartments in cities, where they can get around on foot and where people of various origins live. Current studies by Gregory Martin and Steven Webster of Emory University emphasise that these geographical preferences fail to explain the widening political divide between urban and rural areas. There is a kind of “sorting” going on, as urban Republicans leave cities to live in the countryside while rural Democrats move to the cities. However, this process is much too weak, Martin and Webster point out, to explain the heightening correlation between population density and election results. They come to the conclusion that geographical location exerts a certain influence on voter political preference – not the other way round.

The heightened polarisation since 2008, especially with respect to the increased support for Republicans in rural areas (see fig. 2), has often been put down to the candidacy of Barack Obama and the associated racial element it introduced. However, the 2016 presidential election, during which the polarisation of US politics intensified, has put the economic and cultural concerns of the white lower middle class at the centre of the political debate. This issue is closely related to the economic and social differences between rural and urban areas, since Trump supporters tend to live on the periphery rather than in the main conurbations (see fig. 1). The demographic profile of the average Trump supporter – older, white, without a college degree, and employed in a low-skilled job – is more common in rural areas than in urban ones (see part I). This demographic group is also the one that suffers most from globalisation, not least because of the relocation of jobs abroad.

In her 2016 book “The Politics of Resentment”, which has since become famous, Katherine Cramer, professor at the University of Wisconsin, documented the economic concerns, social fears and resentments of the white rural population towards the white urban upper class in her state. She describes how citizens in rural Wisconsin today feel powerless and ignored because they have the impression that everything is decided in the big cities, and that the cities also receive all public resources while their rural communities are being abandoned. Cramer also highlights how rural residents feel that urban dwellers do not respect them, often considering them to be racist, and patronising them without understanding the challenges of those who live in the countryside or in small communities.

The frustration in rural America that Cramer describes helps explain the success of Donald Trump in the Midwestern states that were decisive for his victory. Trump’s promises to revive rural regions resonated in these states: combating globalisation with re-nationalisation and isolation practices, including job creation in traditional industries, such as mining and manufacturing, as well as by fewer international free-trade agreements; curbing immigration and instituting rules to ensure American citizens have priority on the labour market; modernising infrastructure; and deregulating environmental and industrial sectors to stimulate economic activity. Hillary Clinton’s infamous characterisation of half of Trump’s supporters as “deplorables”, during the campaign, shows how little the Democratic candidate had understood the concerns of rural Americans.

III. Political Implications for the Future

The implications of the urban-rural divide are different for Republicans and Democrats. However, the associated political challenges are vast, both for the president and for the two political parties.

Donald Trump and His Base

During the election campaign, Donald Trump regularly spoke out against cities, which he views as areas of economic and moral decline where violence and drugs prevail – despite the current trend of city centre revitalisation in the US and the associated problems of gentrification. Since moving into the White House, Trump has, in his public statements, cultivated the contrast between his rural or small-community voter base and the urban elites. Trump accuses the latter, with their “swamp” (Washington D.C.), their media (CNN and The New York Times, which he regularly refers to as “fake news”), and their figureheads (primarily Hillary Clinton, but also Nancy Pelosi, the Minority Leader of the House of Representatives), of neglecting common Americans for years. It is interesting to note here that the real estate magnate from Queens who was never recognised or accepted by the Manhattan elite has decided to take the side of rural Americans in his political career.

The first year of his presidency saw open showdowns between the Trump administration and several American cities. Many communities on both the West and the East Coast, as well as metropolitan areas in the heart of the country, such as Minneapolis, Chicago, Denver, New Orleans, and Houston, have all passed laws to thwart Washington’s decisions, against a backdrop of strong mobilisation among residents and local businesses. Tensions are especially great in the areas of climate change and immigration. For instance, many cities, with or without the support of their states, have an active environmental policy, despite Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement. Many have become sanctuary cities, which refuse to extradite illegal immigrants who are obliged to leave the country, yet have committed no crime. Equally, in the area of gun laws, some cities have moved ahead of Washington, introducing more stringent regulations.

The president remains in campaign mode. He continues to organise regular rallies for his supporters, hoping that mobilising his base outside the major conurbations will be sufficient to secure re-election in 2020. He thus makes many domestic and foreign policy decisions (from gun laws to the Iran deal to the relocation of the US embassy in Israel) based primarily on his campaign promises and the support they are likely to generate from his base.

The challenge for Donald Trump is to keep his base happy until 2020. Even if he retains a solid core of the Republican electorate – with 38 per cent of Republicans agreeing with him on “all or almost all” political questions – he will still need to provide concrete results at the end of his term. So far, there appears to be a consensus among experts that the policies of the Trump administration, especially as regards abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), anti-immigration measures, tax reform, punitive tariffs on imported goods, and the “Buy American, hire American” strategy will not in fact contribute to significantly improving the everyday lives of his supporters. If Trump’s policies prove to be counterproductive, as some economic experts fear, rural regions, where his most dedicated supporters live, but which are the most vulnerable to economic downturns, will be the hardest hit.

The Republicans’ Achilles’ Heel

The Republican Party faces its next big challenge in the November 2018 mid-term elections. During their campaigns, GOP candidates traditionally focus on rural regions and the periphery of large cities, since most of their supporters live there. Populist decisions by Donald Trump, however, are meeting with incomprehension in parts of the conservative camp. In this context, some suburbs may represent a potential Achilles’ heel for the GOP. These areas are seen as urban counties (see the definition in part I), but in fact constitute a transitional zone between city and countryside. Today, 55 per cent of Americans live in suburbs of large cities or in smaller urban areas that the Pew Research Center categorises as suburbs.

Although these geographical zones have traditionally been rather conservative, recent statistics show an even distribution between Democrats and Republicans (47 per cent Democrat, 45 per cent Republican). This development may be associated with demographic trends such as the process of diversification resulting from African Americans and immigrants moving from the inner cities. A certain urbanisation of the suburbs is also underway because more and more public transportation and individual businesses are changing the profile of the suburbs, making them more attractive to new population groups. According to Richardson Dilworth of Drexel University, the decision to live in the suburbs today tends to be an economic rather than an ideological one.

Another factor is that many Republicans with university degrees live in the suburbs. Statistics show that they tend to be somewhat more sceptical towards the current president than their fellow Republicans in rural regions. Nowadays, Republican candidates must therefore often run campaigns that attract both of these demographic groups. This can be particularly challenging in elections where gerrymandering plays no role and the competition with the Democrats is real (gubernatorial and Senate elections, for example). For instance, Edward Gillespie, the moderate Republican candidate, narrowly lost the governor’s race in the swing state of Virginia in November 2017. He presented himself as a Trump ally and ran a confrontational campaign. This election was considered a test for the 2018 mid-terms and for the overall mood of American voters. A decisive reason for Gillespie’s defeat, besides the strong mobilisation of Democratic voters, were the poor returns in the suburbs of the Washington D.C. metropolitan area as well as in Virginia Beach, a populous, suburban tourist area on the Atlantic Coast.

The Relatively Conservative Campaigns of some Democrats

After the 2016 debacle, the greatest challenge now facing the Democrats is to win back voter confidence in rural areas and in small and medium-sized cities, especially in Midwestern states. As party insiders admit, the liberal positions of the Democratic elite in almost all social issues may have permanently eroded their support in rural areas. Recent votes have shown, however, that Democrats may be successful if they reach out to rural voters and former workers. These voters were particularly disappointed by the Obama administration and turned their backs on the Democratic Party in 2016. The success of Democrat Conor Lamb in Pennsylvania on 13 March 2018 is considered especially indicative of this potential.

The 33-year-old former Marine and federal prosecutor won a House of Representatives special election in Pennsylvania’s 18th District. In 2016, Donald Trump won there by a margin of almost 20 per cent. The district includes Pittsburgh suburbs where many college graduates live, as well as rural regions where coal and steel production once flourished. Conor Lamb’s campaign, which convincingly combined classically liberal positions with a socially conservative programme, resonated in both areas. While supporting unions and defending the welfare state (including Obamacare, welfare, and Medicare, the public programme providing health insurance to the elderly), he opposed such measures as stricter gun laws. Additionally, as a devout Catholic, he opposed abortion. He also supported Trump’s decision to impose higher tariffs on steel and aluminium imports.

Lamb is not the only one in the Democratic Party who is currently succeeding with similar positions in rural Republican strongholds. Another example is Dan McCready, who won the North Carolina Democratic primary for a seat in the House of Representatives in May 2018 and will be trying in November to be the first Democrat to win the 9th District seat in 55 years. Like Lamb, McCready is a young Christian who emphasises his status as an outsider and a veteran and defends the right to private gun ownership. Both are conducting pragmatic, somewhat conservative campaigns aspiring to attract voters disappointed by Trump. In doing so, they also distance themselves from the party leadership, especially Nancy Pelosi. As a representative of the Democratic elite of San Francisco, she is seen by both candidates as too distant from the concerns of the white lower middle class – much like Hillary Clinton was.

This trend among Democrats raises questions for the next presidential election: Will the Democratic Party learn from its defeat in 2016? Another candidate from one of the two coasts, who comes from elite circles and is unable to attract voters from rural areas and small towns, will therefore probably lose once more. Democratic Party strategists should instead find inspiration in Bill Clinton’s profile: As a white politician from Arkansas, an agrarian Southern state, he was able to reach people of all social groups and thus bridge the urban-rural divide in two presidential elections. It is also a fact that the last four successful Democratic presidential candidates – Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Jimmy Carter, and Lyndon B. Johnson – all had a rural family background. They were able to communicate with conservative rural swing voters as well as with the city-dwellers and minorities that form the traditional Democratic base. Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” comment confirmed the worst fears of many rural voters and showed what her comfort zone was: urban, educated voters who have always supported the Democratic Party. Her comment was also symptomatic of the failure of her presidential ambitions, since no US presidential candidate has ever been able to completely ignore rural America and still win.

Conclusion

The economic and social divide between rural and urban areas is not unique to the US. It is also present in European countries and influences many election results. The outcome of the referendum in the United Kingdom in June 2016 was a shock for many Londoners and residents of other English cities who had spoken out strongly against Brexit. The urban-rural divide also played a role in the last presidential elections in France, as well as in the Bundestag elections in Germany.

What is special about the American situation is the dimension of the chasm between the socio-economic situation of rural residents and those who inhabit the nation’s major conurbations. Equally significant is the influence of political resentment outside the agglomerations on national politics. The 2016 presidential elections brought the scope of this phenomenon to light, thus representing a turning point. This dimension of polarisation in the US is now being taken into account in the campaigns of many Democrats and Republicans. For the 2018 mid-terms and for the 2020 presidential election, many experts recommend observing the political mood in rural regions, without ignoring the mood in many suburbs that no longer speak so clearly in favour of a single party.

Can the divide be closed in future? Several previous attempts were only partially successful. This is true of the rural development programmes under Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society Agenda in the 1960s, and of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) of 2010, which expanded access to health insurance, especially for those with low incomes. Thus, demographers, sociologists, and economic experts are developing new recommendations for improving the situation in rural America.

Brian Thiede of Pennsylvania State University, for example, recommends paying particular attention to the structure of rural economies and communities in order to reduce rural poverty. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs suggests another strategy: enhancing the physical, economic, and social links between urban, suburban, and rural communities. To this end, the think tank recommends intensifying regional planning efforts in order to avoid the wide disparity of effects of political decisions on urban and rural populations. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat considers large cities to be the problem because they are attracting too many resources and jobs. He would therefore prefer to unbundle the country’s largest cities and distribute their administration and businesses throughout the surrounding area. In his book ''“''The Fractured Republic''”'', Yuval Levin of the Ethics and Public Policy Center suggests not only enhancing the principle of subsidiarity, but also paying more attention to the local level. He believes that reviving “mediating institutions” from civil society, such as the family, schools, and religious organisations could help check the polarisation of American politics.

These are all approaches that can be tried out in the future. Unfortunately, several experts agree that it will be difficult for policy-makers to remedy the economic, social, and political dimensions of the urban-rural divide in the short or medium term. The contrast may even become more aggravated during Donald Trump’s presidency, pessimists fear. However, beyond the US president’s political decisions and their impact on the welfare of rural America, this analysis leads to the following conclusion: If, during the next presidential election, the Democratic Party does not succeed in selecting a candidate able to bridge the urban-rural divide, the probability of Donald Trump’s successful reelection will remain fairly high.

– translated from German –

-----

Dr. Céline-Agathe Caro is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Washington D.C. office of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.