Issue: 3/2018

Introduction

Over the last few years, the focus of debates around population growth and urbanisation and their implications for the governance sector has been shifting from Asia to Africa. The reason for this is that the predicted population growth rates for Africa will outnumber the Asian rates by far (see fig. 1 and 2). The overall political management of the challenge facing African urbanisation is also crucial for Europe given the geostrategic positioning of the African continent, and the interdependencies in the fields of economy, stability, food security and migration.

Urbanisation is a defining phenomenon of the 21ˢᵗ century. In 2050, two thirds of people will live in cities and the urban population on the African continent will have tripled. The majority of this growth will take place in low- and middle-income cities especially in Africa and Asia, while the share of growth in Europe, North America, and Oceania is projected to decline steadily until 2050. The London Urban Age Project calculated that in Lagos, for example, the population grows by over 58 people per hour. In comparison, London’s population grows by only six in the same time. With an annual population growth rate of almost four per cent, Africa has the fastest urban population growth rate worldwide, and cities such as Ouagadougou, Bamako, Addis Ababa and Nairobi are currently growing at an even faster rate than that.

However, the process of urbanisation is not only accompanied by new chances and opportunities, but also by enormous challenges. Thus, the level of crime is especially high in metropolises: in a period of five years, 70 per cent of city dwellers in Africa fall victim to a crime. To secure ongoing important technological, economic, urban, environmental, and socioeconomic changes, safety and security need to be improved in African cities, because safety and security play a key role in economic upsurge and democratic development in these societies.

Currently, the question of sustainable urban development is also on top of global develop-ment agendas such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the UN-Habitat’s African Urban Agenda. The newly established goal no. 11 of the SDGs (“making cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”) in particular, shows that urban development is now perceived as an individual topic in its own right, as opposed to one that is cross-sectional. This promises new impetus for much-needed future urban investments and policies, which are vital, especially in Africa.

This article addresses the political relevance of urbanisation, the role of youth and related political fields such as urban governance and safety and security in African cities. The main focus will lie on urban violence and crime prevention as the most innovative and creative policy approaches are currently being developed in this field.

Fig. 1: Africa’s Urban Population Growth 2016 to 2050

Fig. 2: Shares of World Urban Population between 1960 and 2050 (in Per Cent)

Urbanisation and Economic Growth

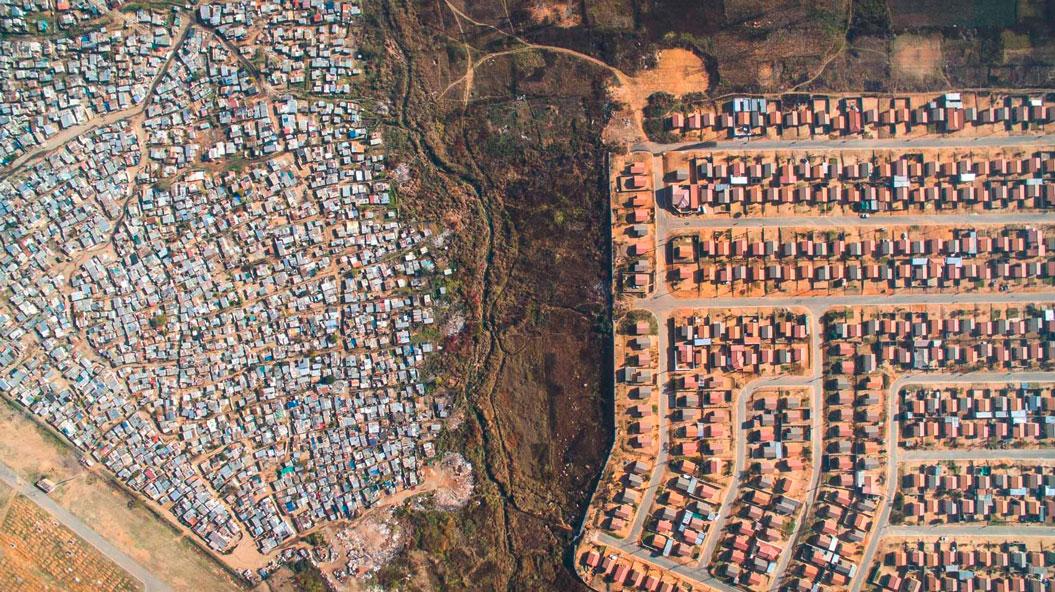

Research from the World Bank indicates that poverty is increasingly urbanising, some experts are warning about the “planet of slums”. The reality is that the majority of urban residents in Africa today live in slums or informal settlements, lack access to basic services, and have an informal low-wage and low-productivity job at best. Even though future improvements in urban poverty reduction are likely, the sheer number of poor (as well as young) people who lack access to the job market as well as to other social, medical or educational services is expected to increase dramatically. The African Economic Outlook 2016 predicts that Africa’s slum population will grow in line with the cities’ population growth. Hence, the aim of minimising urban slum populations will not be realised if the current development of the majority of countries will be followed. Even though such structural hurdles are highly problematic for the economic development of cities, urbanisation also goes hand in hand with great transformative potential. Cities have been and still are engines of economic growth, innovation and productivity. Yet in Africa, urbanisation takes place against the background of urban poverty and inequality.

Furthermore, structural change that takes too long severely hampers the adjustment of the cities and their administrations to the demographic development: there are still too few educational and job opportunities, social and healthcare provisions as well as the supply of electricity and water are inadequate in many places and young people’s future prospects are bleak.

Yet, more and more people, and especially the youth, migrate to the cities. Dissatisfaction with the public administration, as well as the implications of climate change and armed conflicts are the main reasons for rural exodus in Africa. In contrast to Latin America, Africans do not necessarily expect better employment opportunities from migrating to urban areas. New studies show that there is no real correlation between economic development and urbanisation in African cities as we witnessed in Europe decades ago.

According to the African Economic Outlook, this “urbanisation without growth” has exacerbated the consequences of slow structural transformation in Sub-Saharan cities. Economic development continues to positively effect urbanisation dynamics, but urbanisation in Africa can and does happen in contexts of low growth. At the moment, we can see this for example in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where the GDP per capita is one of the lowest worldwide yet the country’s level of urbanisation is in line with the African average. In addition, countries such as Angola and Nigeria are urbanising rapidly despite the lack of industrialisation. These factors need to be analysed and monitored more carefully since we know that there is a link between urbanisation and development; higher levels of urbanisation generally correspond to higher levels of human development and vice versa (measured according to the HDI; see fig. 3). This is not yet the case for sub-Saharan Africa. Here, given the high official und even higher unofficial unemployment rates, the informal labour market in particular should be the focus of attention and subject to more in-depth analysis in regards to urban planning and development measures.

The Aspects of Safety and Security– Reasons, Challenges and New Crime Prevention Strategies

Violence and Crime in Cities

Incidents of violence, whether politically or criminally motivated, are common in Africa’s cities, and, just like poverty, violence is urbanising. Crime rates are always much higher in large cities than in small cities or rural areas. In most cases, urbanisation is inextricably linked to high rates of crime and violence due to factors such as extreme inequality, unemployment, inadequate services and health provisions, weakening family structures, less social ties, social exclusion and overcrowding.

Furthermore, armed conflicts, riots and protests are on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa, too. The often oppressive state responses to protests are also a problem. In South Africa’s Gauteng province (home to Johannesburg and Pretoria), for example, people took to the streets on average more than 100 times each year between 1997 and 2016 – more often than in any other African megacity region. Unplanned, overcrowded settlements populated mostly by marginalised youth can be hotbeds for violence. Armed conflict has triggered rural-urban migration, and hence accelerated urbanisation. This is currently the case in the DRC and in Nigeria.

Violence and conflicts weaken the democratic and economic development of cities and contribute to decreased levels of economic growth even of entire national economies. Conversely, there is a strengthening of local democracies and economic development if a decrease in violence, conflict and crime is achieved.

It goes without saying that private and public investors avoid high-risk districts and this negatively affects the socioeconomic stability in the country as well as the population’s quality of life. Even just a perceived lack of security poses a risk to a city’s sustainable development.

Fig. 3: Levels of Urbanisation and Human Development Worldwide Represented by Human Development Index (HDI) Rating

Safety and Security and the Youth Bulge

We refer to a “youth bulge” if at least 20 per cent of the population is between the ages of 15 and 24. This age group makes up the majority of both victims and perpetrators of crime everywhere in the world.

The role of the youth needs to be a critical focus area in light of urban demographics in Africa (see fig. 4). Africa has by far the youngest population worldwide, and younger people are generally more prone to migrate to urban areas than older ones. This boosts the proportion of the working-age population in cities and potentially contributes towards economic dynamism. On the other hand, the exclusion and marginalisation of urban youth may also increase the risk of urban violence.

The role and impact of young people on democratic and participatory governance as well as on economic development and social cohesion are important for every society and any future democratic development. According to some, the youth represents huge potential for the development of democracy in the future, while others are more pessimistic and correlate, for example, the numbers of young people (mainly of young men) with the likelihood of violent conflicts – however, the majority see a stronger link between jobs, poverty and violence. Young people without proper school education or vocational training are more likely to commit crimes due to their experienced or perceived lack of individual development perspectives. If the youth cohort is reasonably well educated but there are no jobs, this will often trigger youth protests and cities are the main locus of these protests for the most part. The well-known “Arab Spring” uprisings in 2011 exemplify these types of urban protests; we now increasingly see them in sub-Saharan Africa, too. In Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, urban youth-led protests in 2014 led to the resignation of long-term President Compaoré after 27 years in power. In South Africa, so called “service delivery protests” were shaking communities and the hegemony of the ruling African National Congress (ANC). Another very prominent example are the #FeesMustFall student protests witnessed in South Africa over the last few years, which finally shed light on other political fields such as social cohesion etc.

Fig. 4: Median Population Ages across the World

This is why the youth needs to be the focus of political education measures; otherwise, social apathy, violence and crime will increase dramatically in urban areas. Young people must partici-pate in societal debates and have a voice in the political arena. If the youth have no real voice in society, the resulting frustration could lead to a feeling of abandonment by society and easily turn into acts of violence and crime.

Youth violence and juvenile delinquency must not be overlooked when it comes to international cooperation. It results in high economic and social expenses, alienates internal and external investors and is generally considered one of the greatest barriers to development.

Abb. 5: Anteil der städtischen und ländlichen Bevölkerung in Südafrika von 1950 bis 2050 (in Prozent)

Crime and Violence Prevention Strategies in South Africa

Similar to other African countries, urbanisation in South Africa is striking. Whilst 52 per cent of the population lived in urban areas in 1990, 71 per cent will live in urban areas by 2030 and the figure will rise to 80 per cent by 2050 (see fig. 5). In addition to the facts already mentioned, the legacy of socially and spatially segregated urban development during apartheid plays a crucial role in South Africa. Violence and crime is particularly concentrated in urban centres. The South African government has developed a comprehensive national violence prevention policy (White Paper on Safety and Security); however, implementation at the local level is generally weak. The country has a very high rate of murders, assaults, rapes, and other crimes compared to most other countries. Crime rates have declined since the end of apartheid, but they remain 4.5 times higher than the global average. Unfortunately, the most recent statistics do not reflect this decline. In the last four years, the murder rate has again increased by 20 per cent and the number of armed robberies has risen by 30 per cent. This happened during a period when the South African Police Service (SAPS) annual budget increased by 50 per cent. Much of this undesirable development is associated with poor political appointments, arguably due to corruption linked to former President Jacob Zuma.

Crime Prevention in Townships: Hotspot Policing and Urban Upgrading

The described decline in the murder rate over the first two decades of democracy in South Africa was primarily due to the introduction of a new series of SAPS deployment strategies, shifting the focus towards “hotspot policing” or “high density policing” operations. The interventions exclusively focused on the townships (South African term for slums) and their micro hotspots such as hostels, shebeens (formerly illegal bars) and taxi ranks. Reasons for violent crime in these hotspots are mainly alcohol and firearms misuse combined with youth unemployment, weak social cohesion and social norms that are generally pro-violence. During such operations, SAPS members are usually heavily armed and deployed in battle-ready formations with the support of armoured personnel carriers and helicopters. Soldiers from the South African National Defence Forces accompanied the police on many occasions. Today, SAPS have taken a more passive and complementary approach of policing urban hotspots and is moving towards community-oriented policing models, as is the case in many other countries. In the meantime, community policing has become the organisational paradigm of public policing in South Africa.

“Through community policing governments can develop the self-disciplining and crime-preventive capacity of poor, high-crime neighborhoods. Community policing incorporates the logic of security by forging partnership between police and public. Since safety is fundamental to the quality of life, co-production between police and public legitimates government, lessening the corrosive alienation that disorganizes communities and triggers collective violence. Community policing is the only way to achieve discriminating law enforcement supported by community consensus in high-crime neighborhoods.”

In one of the largest and most violent townships in Cape Town, Khayelitsha, local gang wars led to the temporary shutdown of all services delivered by the city. During a six-month gang war between the “Taliban” and the “America” gangs, schools were closed, transport was disrupted and health services in the community were restricted. As this example shows, crime is concentrated at specific places. Against this background, in June 2018, South Africa’s Police Minister announced a new “high density stabilisation intervention” to tackle crime. It includes the deployment of desk-based police officials to the streets, particularly in “identified hotspots” such as Khayelitsha in accordance with the new community-policing philosophy.

“Hotspot policing” is now more often accompanied by social and infrastructural crime prevention initiatives. In Khayelitsha, for example, a municipal project called “violence prevention through urban upgrading” aims at reducing crime, increasing safety and security and improving the social conditions of communities through urban improvements and social interventions. The project is unique in South Africa insofar as it integrates all forms of development concepts and not only the infrastructural upgrading of urban spaces. The project combines planning efforts by state institutions with community-based protection measures. This includes the connection of policy frameworks, private security and neighbourhood watches and the easier access to justice for residents. The project uses different lenses, one being the “Situational Crime Prevention” approach. The term “Situational Crime Prevention” seeks to reduce crime opportunities by increasing the associated risks and difficulties, and reducing the rewards. It is assumed that positive changes in the physical environment ultimately lead to safer communities. Changes such as the “Active Boxes” are to be used for this approach: small three-story buildings with offices, a caretaker flat and a room for community patrollers, which are built close to the so-called “micro hotspots” mentioned above. Another aspect of the project is the “Social Crime Prevention” approach that promotes a culture of lawfulness, respect and tolerance. The project focused on three areas: patrolling street committees combined with law clinics (in collaboration with the University of the Western Cape) and social interventions such as school based interventions and early childhood development programmes. The implementation is carried out using local resources to the greatest extent possible. A visible decrease in crime rates in Khayelitsha has been recorded since implementing the project.

Crime Prevention in South African Suburbs: “Cities Without Walls”

The counterpart to the townships are the wealthy South African urban suburbs. South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world, which these suburbs are a clear reflection of. At the end of apartheid, South African suburbs began to change dramatically due to rising levels of crime. This is a typical development for countries in transition, particularly for those characterised by high levels of inequality. With the demise of the inner city economy, businesses, together with their employees, started to move to the South African suburbs. The inner cities were abandoned and crime became widespread. With the associated increase in the fear of crime, suburb dwellers built higher walls and erected electrified fences as a means of defence. This initially attracted strong support and was bolstered by the private security industry, which had vested interests in the rush to monitor space and strengthen security. To date, high walls have become a part of the accepted landscape in the suburbs. New research has now proven that crime rates are higher in places surrounded by walls. Solid, high walls are viewed as an obstacle to policing. Furthermore, natural surveillance by neighbours and patrolling by police or private security services are limited. Against this background, another interesting approach to tackling crime is the “city without walls” project in Durban where academics, the Metropolitan Police Service, private security firms and local communities are working together. The objective is to challenge the perception of crime, to eliminate the perception of alienating neighbours and to strengthen a cohesive community. Selected communities and institutions such as the Alliance Française and the Goethe-Institut participated in the project, tore down their own walls and replaced them with transparent and see-through fences or walls. Research proved this pilot project to be successful: lower crime rates and more social cohesion in the pilot communities.

Conclusion: The Increasing Power of Cities and the Role of Good Governance

Cities in Africa have enormous potential to provide sustainable solutions to democratic development. They offer opportunities for social and economic change and participation but also for political protest and unrest. Unfortunately, there is a lack of urgency within local city governments to respond to these challenges and opportunities in a sustainable way. The reasons for this is that they are overloaded with other (social) problems, they are not equipped with the necessary knowledge and infrastructure, and they are not willing to see this problem for what it is: a real danger to future democracy in Africa.

To ensure that the upcoming urbanisation translates into sustainable development, African cities need far better urban planning and innovative approaches that are tailored to their diverse urban realities. It is therefore important to foster political education and participation among the youth. Civil society together with political parties or political movements can be strong drivers to initiate dialogue and create platforms for engagement; however, local governments and authorities must always be involved in such processes.

The community-based and people-oriented policing approaches in South Africa after the end of apartheid are an example of how modern African administrative structures could be organised. On the other hand, exaggerated state police violence as we saw recently in the DRC, Ethiopia, Burundi, Zimbabwe and Tanzania (against the political opposition) destroys trust in the police and in democracy, as well as leading to more aggression and a vicious circle of violence, aggression, prejudice and mutual rejection. As a result, young people develop deep hatred against the police and hence against the state itself. In this context, policing needs to be seen as a diverse and pluralistic set of social acts. Policing in African cities will also need to stay abreast of the current technology (including social media) for an enhanced system of communication with the local communities and to therefore improve safety in urban spaces.

The newly established “Institute for Global City Policing” at University College London stated that due to the emerging political power held by city governments, they should be seen as “change agents of the future” or “change drivers”. In some cases, megacities now already have more political power than nation states. In light of this, local governments become more important in the national and the global context and need to be included as new players in global political processes such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the UN Conference of the Parties (COP) or the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). There are now a number of African cities in which progressive or liberal non-socialist opposition parties govern big cities or capitals (e. g. Johannesburg, Cape Town, Pretoria, Harare, Bulawayo, Dar es Salaam, Addis Ababa) and they often follow different approaches in regard to tackling crime and violence than those of the national government. Such a “non-coherence” of urban policies and strategies could hamper urban development, but in other scenarios, this could also lead to more independent and stronger cities. As regards security aspects, it could also lead to a stronger politicisation of the urban space including more political protests, demonstrations and violence.

The legitimacy of the people charged with ensuring public safety and order must be a key emphasis in every security environment. Increases in the numbers of police or the army should not necessarily be the best antidotes to insecurity. Military and policy exchange, as currently witnessed between the Colombian and Nigerian or the Malian and European police forces concerning the fight against local terrorism for example, together with an extended community or partnership approach would be an ideal framework for tackling future challenges. The root causes of crime and the foundations of law and order can be found in the nature and dynamics of each society. Therefore, a democratic, equal and just society based on the rule of law is the best prevention of crime and violence. Recently, the African continent presented an abundance of positive examples. Decade-long leaders or dictators together with their patronage networks were urged to step down to make room for political improvements and reforms (e. g. in Angola, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, South Africa, The Gambia) – these positive developments will trickle down to the local level and guide the process for more people-centred local government politics.

-----

Tilmann Feltes is Desk Officer in the Team Sub-Saharan Africa at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Until 2017, he was Trainee at the Stiftung’s office in South Africa.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.