Issue: 3/2024

There is no uniform “political centre” in Spain. In the last national elections in 2023, the two main parties, the centre-right PP (Partido Popular) and the centre-left PSOE (Partido Socialista Obrero Español), which is drifting further to the left, each won more than 30 per cent of the vote and together achieved just under 65 per cent. On the face of it, the losses of the far-left and right-wing populist parties can also be seen as a stabilisation or even a strengthening of the political centre. However, none of the major parties in Spain clearly define themselves as centrist, but rather position themselves as centre-left or centre-right.

The term “political centre” is vague or open to interpretation. Extremist forces now claim that positions or attitudes that were deemed centrist 20 years ago are either “right” or “left” in order to combat them as part of their political tactics. Historical experience and increasing polarisation in recent years explain the Spanish parties’ reluctance to aim for the centre as a political category.

Spanish Centrist Parties Have Historically Failed

The centrist UCD (Unión del Centro Democrático) under the leadership of Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez played a key role in the transition phase from Franco’s dictatorship to full democracy between 1975 and 1982. True to its name, it was a moderate, partly Christian social, partly social-liberal reform party that pursued centrist policies. It succeeded in becoming the strongest force in parliament in the first national elections in 1977, winning 165 of 350 seats as a centrist party. This position of strength enabled the UCD to forge groundbreaking compromises across the whole political spectrum from right to left. In this exceptional political situation, all parties set aside ideological differences where necessary in order to advance the transition. According to polls at that time, most Spaniards also positioned themselves in the centre.

Nevertheless, the UCD failed to establish its centrist concept over the long term. A variety of internal party currents tended to bring lines of social conflict into the party and government instead of projecting them onto political competitors. To a certain extent, the UCD became a victim of its own success. When it came to resolving systemic issues, it was able to mobilise more apolitical voters. But following the adoption of the democratic constitution in 1978, the importance of its centrist concept began to wane and conflictive, ideologically charged economic and socio-political issues came to the fore. In the 1982 national elections, the UCD gained only eleven seats. For the first time, the strengthened PSOE (202) and the Alianza Popular-PDP (107) divided the Congress of Deputies along centre-left/centre-right lines.

With the rise and fall of Ciudadanos, the second attempt in recent Spanish history to establish a (new) political grouping with a centrist concept has also failed. Originally social-liberal, the Citizens’ Party (C’s) was initially founded in 2006 as a regional, constitutionally loyal alternative to the Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSC), which had increasingly moved closer to the Catalan separatists. Ciudadanos grew rapidly and seemed to be unstoppable, reaching its peak in 2017 with 36 out of 135 seats in the regional parliament of Catalonia (25.35 per cent) and with 57 out of 350 mandates in the national parliament in April 2019 (15.9 per cent). It looked as if it was on its way to becoming a liberal party in the centre between the then more conservative PP and the socialist PSOE.

After the failure of the Catalan separatists, C’s quickly lost relevance. In a way, history was repeating itself: as the Catalan bid for independence faded into the background as a temporary political anomaly, the party found it increasingly difficult to communicate a consistent political direction. The downright contradictory positioning on the spectrum from liberal-conservative to social-liberal on the regional level as well as tactical coalition manoeuvres with both the PP and the PSOE, fostered the negative image of Ciudadanos as an uncertain, undefined and ultimately superfluous political player. Following a few years of agony, C’s disappeared from all regional, national and European parliaments in elections held in 2023/2024.

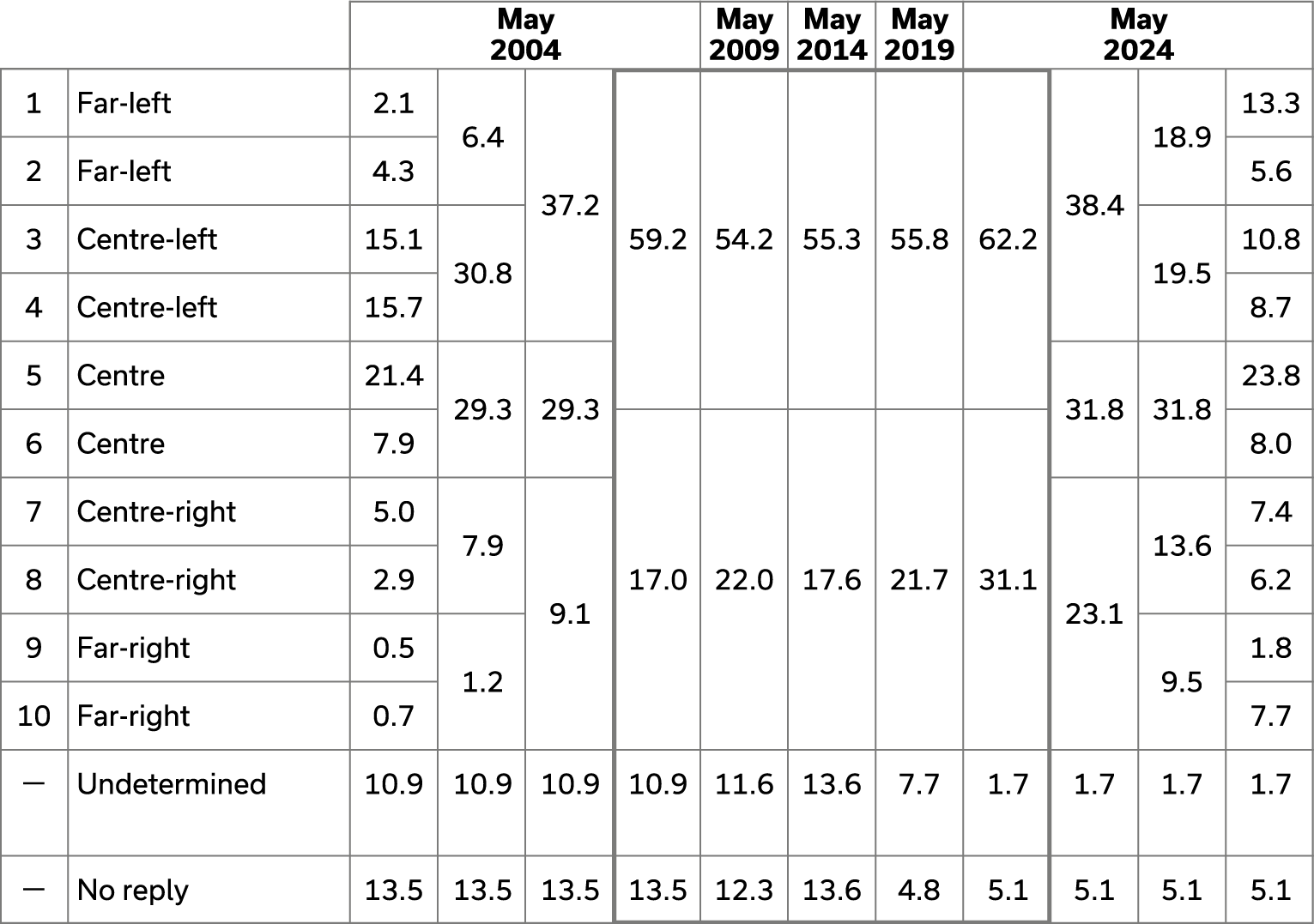

It is worth contrasting these past developments with how the Spanish electorate positions itself on the political spectrum in terms of ideology. Today, just under a third of Spanish voters align themselves with the poltical centre in a narrow sense (31.8 per cent), as they did 20 years ago. 38.4 per cent of voters place themselves on the centre-left to far-left of the political spectrum, while 23.1 per cent position themselves on the centre-right to far-right. Overall, Spanish society therefore positions itself more to the left of the centre.

The number of people who categorise themselves as far-left has more than doubled in the past two decades. Similarly, the number of those who categorise themselves as far-right has also increased. From the additional finding that there are currently considerably fewer undecided voters, it can be concluded that Spanish society has become increasingly politicised (see figure 1).

Fig. 1: How Spaniards Position Themselves in Terms of Political Ideology (Random Sample Taken from May 2004 to May 2024, in Per Cent)

At this point, it should be noted that the term far-right in Spain is not identical with the German definition of far-right. It should also be noted that many Spanish regionalist voters “automatically” perceive themselves as left-wing because the Spanish left – in contrast to many more unitary, centralist socialists in Europe – has positioned itself as a supporter of more extensive autonomy rights. The historical reasons for this lie in the opposition to the Francoist unitary state.

Courting the “Silent Majority”

In light of these figures, the two major parties, the PP and PSOE, are aware that they need to achieve two strategic aims. On the one hand, they need to fulfil their respective core electorates’ desire for a clear ideological positioning, preventing the “all things to all people” approach that is typical of the centre ground. On the other hand, they have to appeal to the almost 32 per cent of voters who identify themselves as true centrists. There is talk of the “strategic centrality” or the “silent majority” of the rather apolitical citizenry that the PP and PSOE are striving to attract. In concrete terms, they have traditionally made a clear ideological left-right distinction in their election campaigns and day-to-day political rhetoric, but have tended to be moderate in actual government.

The PP illustrates just how complex and risky such a balancing act is. At the end of 2011, after winning an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections, it defined itself as a “reformist party of the centre”. The PP’s intended shift towards the centre at that time was accompanied by the emergence of the far-right Vox party, a de facto offshoot of the PP. The PP’s worst performance in the national elections in November 2019 coincided with Vox reaching its peak by winning 52 out of 350 seats. This was a clear signal of protest by Vox voters, rejecting centrism and the perceived “dilution” of attitudes regarding loyalty to the constitution, the constitutional monarchy, patriotism, the family, and so on. In this case, the PP’s shift towards the centre that began in 2011 was not a step towards gaining more votes, but instead paved the way for a political competitor that was, at least initially, its own offspring, namely Vox.

The PP’s current party leader, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, is attempting to exploit “strategic centrality” by adopting a decidedly moderate stance and offering a conciliatory programme to very different milieus. After all, the results of the 2023 national elections highlighted how the PP cannot form a majority government solely by appealing to voters on the right of the centre. By appealing for centrality and moderation, Feijóo also seeks to improve a situation for which he justifiably holds the current left-wing government, and above all its leader Pedro Sánchez, largely responsible: the enormous polarisation of political culture. In this sense, Feijóo has described the PP as a “centre-right reform party” since 2023.

Manifestations of Polarisation

Both internal and external observers have noted a sharp increase in polarisation in Spain. As correct as this finding is, it seems necessary to differentiate between constructive polarisation, which can in fact stabilise Spanish democracy, and authoritarian polarisation, which damages the political culture and even endangers the system. In Spain, it is more important than ever to speak of polarisation in the plural.

Polarisation through the Fragmentation of Parliament

In the early decades of young Spanish democracy, a stabilising two-party system emerged (bipartidismo). This did not mean that there were only two parties. On the contrary, the Spanish party system has always been characterised by a plurality of parties. Yet the PP and the PSOE were by far the largest political forces. They invariably provided the head of government, occasionally alternating, and had small partners at their side. There was no centre in the narrower sense – voters could choose between two clear alternatives. The partners were so small that the major parties were able to implement their core policies.

This alternating system of power distribution gave rise to the anti-system party Podemos in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the liberal Ciudadanos after 2006 and the right-wing populist party Vox in 2013. The challengers Podemos and Ciudadanos came close to overtaking the two established parties PSOE and PP in terms of parliamentary seats (sorpasso). In the 2016 elections, Podemos won 5.1 million votes, almost as many as the traditional labour party PSOE, which received 5.4 million votes, while Ciudadanos won only nine seats less than the PP in April 2019 (57 vs. 66 seats). The new parties’ increased weight made the political system more unstable. Since 2015, there have been five new elections to the Congress of Deputies and the Senate, resulting in relatively fragile minority governments and a fragmented parliament with up to 19 different parties. In 2019, the PSOE and PP only received around 11.8 million votes in both elections – less than 50 per cent of the vote.

The nationalist regional parties have always been represented in parliament due to an electoral system that favours them, but due to the slim majority have disproportionately increased their ability to shape, or rather block policies. Political groups such as the far-left Basque EH Bildu, a successor organisation to Batasuna, the banned former political arm of the terrorist organisation ETA, have benefited from increasing “normalisation”, or even upgrading, especially by Pedro Sánchez. At present, Sánchez’s minority government is dependent on the successor organisation to Podemos, the Sumar electoral platform, as well as the four nationalist-separatist parties in the Basque Country and Catalonia. The latter can now enforce maximum regionalist demands such as the amnesty of convicted rebels, transfers of powers or financial relief at the expense of Spain as a whole.

These partial territorial conflicts are exacerbating polarisation in Spain. Any kind of coalition between the PSOE and PP is currently inconceivable. Existing barriers to the fringe parties are in many cases even less easy to overcome: Podemos, EH Bildu, Esquerra Republicana, CUP and the Galician Bloc reject any active cooperation with the PP as this could mean an irreparable loss of trust among their voters.

Pedro Sánchez ensures his political survival largely through polarisation. He has consistently rejected agreements with the moderate PP and favoured concluding agreements with extremists and separatists. In terms of rhetoric and content, his election campaigns basically came down to a dichotomous “us” versus “them”. By “us”, he meant all “progressive” forces, and thus all those who were not PP or Vox – regardless of their substantive positions. Under “them”, he subsumes PP and Vox, which he basically describes in the same breath as the “right and far-right”, against which his progressive majority must build a dam, even a “wall”. Sánchez has thus defined half of Spaniards as being outside the democratic spectrum.

Polarisation Due to Differing Economic and Socio-political Ideas

In terms of economic policy, in Spain we also see the classic polarisation between the more statist left and the more liberal right. However, it is positive to note that, particularly in the autonomous regions, both the PP and the PSOE are pursuing less ideological and more pragmatic approaches.

Another, deeper layer of polarisation between the camps is likely to be a fundamentally different view of the world, society and family – something that is difficult to resolve through negotiation. The Sánchez government, and particularly its coalition partners Podemos and Sumar, adopted socio-political laws based on the conviction that institutions such as “the parties”, “the family”, “the church” and representative parliamentarianism are essentially undemocratic. In their opinion, “the system” oppresses disadvantaged collectives (“migrants”, “women”, and so on). The affected collectives must be emancipated from these “powers” through politics, which is to be achieved by prioritising social rights over individual civil rights.

Examples of this attitude are laws that allow minors to have an abortion or change their gender without their parents’ consent. Parents are to be pushed ever further out of the education system. Parents are fighting back and criticising the fact that state authorities are increasingly transporting the ideology of Podemos, Sumar and the PSOE into the classroom.

From the left’s perspective, all these measures advance the “progress” and “modernisation” of Spain. The PP is deeply opposed to such trends, believing that the left-wing government has in fact divided society. Contrary to the left’s election campaign slogans, the PP does not want to return to the old way of doing things, but instead to tone down excessive responses, for example by promoting cooperative rather than confrontational feminism. In any case, social policy is another source of polarisation.

Polarisation as an Expression of a Divergent Understanding of Democracy

For years, political observers have noted an erosion in Spain’s institutions. This includes an unprecedented politicisation of the judiciary, which found expression in long-standing conflicts over the appointment procedures at the Spanish Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional) and the highest judicial authority, the General Council of the Judiciary (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, CGPJ), which were only recently resolved.

First and foremost, there are tangible political interests underpinning the blockade. Those holding the reins of the judiciary have greater power to implement political decisions. The PP accused the PSOE of undermining the separation of powers given that Sánchez systematically places political loyalists in top positions within public institutions in the judiciary and beyond. Conversely, the PSOE accused the PP of not recognising the new realities of power and wanting to preserve traditional power structures.

In June 2024, a highly controversial amnesty law came into force for ringleaders of the unconstitutional Catalan independence referendum of 1 October 2017 who are still being prosecuted or have already been convicted. Up until the national elections on 23 July 2023, Sánchez had always ruled out such a law because he deemed it unconstitutional. A clear majority of constitutional experts and judges still hold this view today.

Beyond all the legal implications, it is politically relevant that the judiciary is directly subjected to politics in several respects. It is, in fact, a deal: impunity in exchange for retaining power. Specifically, Sánchez secured the seven votes from the Catalan separatist Junts party required for his re-election by changing the law specifically for their leaders and in their favour.

Nevertheless, Sánchez dismissed the subsequent massive criticism of this undermining of the separation of powers and the principle of equality of all citizens before the law by large sections of society and many professional organisations with the argument that it was merely an alleged “fascist sphere (fachosfera) that wanted to overthrow his government”. The judiciary feels discredited. The intention of the PSOE and Junts to set up so-called control commissions in parliament to “scrutinise” court rulings contributes to this. Behind this plan is the accusation of “lawfare”.

Widespread critical reporting on corruption scandals in Sánchez’s closest political and even family circle led to him targeting the media that criticised him. Sánchez announced “measures to preserve democracy”. Consequently, this is seen as an attempt at intimidation and an attack on the freedom of the press. Unsurprisingly, these events are significantly contributing to the processes of polarisation. There is only for and against here, no moderating position.

These events and, above all, the way they are handled, reveal a drifting understanding of democracy. Sánchez and his closest supporters see themselves as progressive innovators of democracy, in which the will of the people must become directly effective. Its progress and exercise of will must not be hindered by traditional power structures in institutions that have always been supposedly dominated by the “right”. It must be borne in mind that the PSOE has now governed at national level for a total of 27 years, while the PP has only been in power for 14.5 years, which means the Socialists have exerted far more influence on the configuration of the Spanish political and judicial system than the PP. However, Sánchez is now reversing this rhetorically because he does not have a clear majority. To put it bluntly, according to the left-wing narrative, democracy must be “democratised”. Although numerous elections in 2023 and 2024 objectively caused the left-wing parties in particular to suffer severe electoral defeats, the election losers are postulating a “social majority”, alluding to the mere sum of all political forces beyond the PP and Vox. This legitimises the complete exclusion of right-of-centre parties from political decision-making.

What Sánchez declares as an improvement to democracy is strongly criticised by his opponents; the latter view it as hugely damaging to Spain’s representative democracy, which is based on the separation of powers. They see signs of a system-changing, creeping authoritarianism in the way the law is handled and in the attacks on the judiciary and the press. For the PP and Vox, the 1978 constitution represents the crowning achievement of the unifying transition from the Franco dictatorship to full democracy, and it must not be infringed upon under any circumstances.

This is giving rise to a new polarisation: representative democracy versus a “popular democracy” based on Latin American Bolivarian models such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador. A worrying negative dynamic is underway that does not currently allow for a moderating centre.

Geopolitical Context of Polarisation

The polarisation in Spain, as in other EU countries and worldwide, is not determined by domestic policy issues alone. Russia, for example, is also trying to exert influence on Spain. Vladimir Putin’s conservative and religious ultra-nationalism holds a certain appeal for far-left, far-right and separatist movements in Spain.

The far-left parties Sumar and Podemos have never officially condemned Stalinism, which claimed many millions of victims. Sumar and Podemos also show understanding for Putin’s expansionist course towards the West as a supposed countermovement to NATO, which they reject. Both have been able to keep Spanish arms deliveries to Ukraine relatively low since 2022 thanks to their participation in the coalition.

Court hearings on the accusation of treason in the context of the unconstitutional referendum in Catalonia on 1 October 2017 are still ongoing. Among other things, Putin’s support for the then regional president, Carles Puigdemont, via agents and media messages will be assessed.

The discourse of religious and nationalist patriotism is becoming increasingly appealing to the national conservative to right-wing populist Vox. Having recently cut its liberal wing, the national party leadership around Santiago Abascal is drifting ever further in the direction of an eastward-looking ultra-nationalism. This has been reflected in the European Parliament in its departure from the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) and its turn towards the identitarian “Patriots” around Viktor Orbán.

Russian troll farms on social media are feeding their polarising messages into all of the aforementioned voter sectors. Time and again, there are also rumours and investigations into alleged flows of Russian money to Russia-friendly fringe parties and media in Spain.

Polarisation and the Functionality of the Political System

The effects of the multiple polarisations are most visible at national level – to the point of blocking reforms. PP leader Feijóo had offered Pedro Sánchez several “state pacts” on territorial organisation, economic and social policy, Spain’s foreign relations and so on. Yet, this will not happen as long as Sánchez benefits more from polarisation than from cooperation with the largest opposition party.

Due to its heterogeneity, the Sánchez government has no common political project beyond the empty formula progresismo (progress). For example, at NATO summits, Sánchez pledges the two per cent target to strengthen Europe’s defence capabilities, whereas his coalition partner Sumar opposes this. The nationalist-separatist regional parties are demanding transfers of powers, debt relief and other financial benefits; against which even PSOE representatives from the other autonomous regions are levelling criticism because they see it as unequal treatment. When it comes to economic and social policy, the left-wing and right-wing parties that support the government are worlds apart. A budget for 2024 could not be drawn up due to major differences and it remains uncertain whether there will be a new budget for 2025.

Spain’s advantage lies in its distinctly federal, autonomous structure. This means that blockades at national level are compensated for by regional governments capable of taking action. Spain’s public administration works well, too. Despite all the problems, the provincial cities have managed to drive innovation, digitalisation and industrial development. The country is very active in environmental policy, although there is no explicitly green party.

It is also worth recalling that the share of votes for the two major parties increased to just under 65 per cent in the most recent national elections. The extreme parties Sumar and Podemos on the left, and Vox on the right, have lost significant ground and now only account for one third of the votes of the major parties. The regional parties have lost voter support, too. Their excessive influence on politics is due to Sánchez’s fragile situation and is therefore likely to be only temporary. All these facts stabilise Spain in the extended centre.

And not all polarisation is detrimental. Democracy thrives on the pluralism of concepts and opinions. Constructive polarisation offers voters alternatives. While strong opposition strengthens democracy, branding every rejection of government proposals as “polarisation” violates this vital element underpinning all parliamentarianism. Polarisation becomes dangerous, however, when it is so radical that it abandons the common understanding of democracy and the common constitutional basis.

More Cooperation, Less Division?

In Spain, there is no comparable drive towards the political centre as is the case in Germany. Due to their different historical experiences, people openly admit to being on the left or right. Nevertheless, the “right-wing” category in Spain is still a long way from extremist or even fascist thinking as they are defined in Germany; even if it is important to keep an eye on the extent to which Vox is becoming radicalised by its rapprochement with Viktor Orbán. The PSOE is (still) comparable to the German Social Democrats. The fact that the leader of the Communist Party can be deputy head of government can be explained by the lack of experience of a communist dictatorship in Spain.

The majority of the Spanish population would like their respective parties to adopt a clear position. In their view, no so-called “centre party” could provide such clarity, with too many “all things to all people” positions on key issues such as more or less state involvement in the economy and education, more or less national unity or more or less privacy in educational matters. Nevertheless, prior to elections, the major mainstream parties try to win majorities among the volatile groups of voters in the strategic centre who do not have a strong ideological commitment.

Clear positioning means a stronger polarisation of political culture, which is perceived by outside observers and Spaniards alike. To a certain extent, offering real alternatives stabilises Spanish democracy. However, we currently witness how Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez in particular is using polarisation as a mobilisation tool and a political survival strategy. The most visible sign of this is his adamant rejection of compromises with the largest (opposition) party in Spain today, the Partido Popular.

Conversely, there is hope that the current intensification of polarisation may be temporary. Once Pedro Sánchez is no longer head of government and PSOE leader, there could be a way back to greater moderation and cooperation between the major parties and thus to the political centre. A comparative analysis of the election manifestos for the 2023 local, regional and national elections provides one reason for this optimistic outlook, with the surprising finding that the positions of the PP and the PSOE in particular are largely compatible when it comes to society’s “real problems” – such as jobs, inflation, healthcare, education, justice, the environment and finances. The PP undeniably favours liberal solutions, especially in economic policy, while the PSOE prefers to rely on the guiding and active role of the state to correct the assumed “market failure”. The PP emphasises strengthening the individual in social, family and education policy, whereas the PSOE focuses more on community institutions. Unlike the election programmes of Vox or Podemos, however, neither the PP nor the PSOE contain extreme, irreconcilable policy approaches. Coalitions or at least selective agreements (pactos) would be entirely possible.

The Spanish parties do not strive to occupy the centre ground. Nevertheless, Spain has succeeded in building a stable democracy with a distinctive structurally moderately polarising extended two-party system (bipartidismo). Almost contrary to the overall European trend, extreme forces on the left, right and separatist spectrum are losing support among the population in Spanish elections. It remains to be seen whether and what long-term consequences the negative polarisation induced by the Sánchez government will have for Spanish democracy.

– translated from German –

Dr Ludger Gruber is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Spain and Portugal Office based in Madrid.

Martin Friedek is a Research Assistant at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Spain and Portugal Office.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.

Topics

Austria's political centre under pressure

Elections in Greenland

Bundestag election 2025: France hopes for policy change in Germany

No clear winner in the parliamentary elections in Kosovo: Forming a government will be complicated

Canada faces the threat of a trade war with the U.S. in this election year!