Issue: 4/2024

What began more than 18 months ago as a battle between two Sudanese military officers for control of central power in Khartoum has now not only plunged Africa’s third largest territorial state into total chaos, but has also shifted the political tectonics at the crucial hinge between the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and the Sahel region. The countries most affected by the war in Sudan are Egypt, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Uganda, Chad and Libya, which together are home to almost a quarter of Africa’s total population.

The commander-in-chief of the regular Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), Lieutenant General Abdel Fatah al-Burhan, and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, the commander of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which were formed more than 20 years ago, were unable to agree on the exact distribution of power following a brief period of joint rule. This led to the outbreak of fighting between the military and paramilitaries in the Sudanese capital on 15 April 2023. Initial hopes of a quick start to meaningful negotiations have been dashed a long time ago. The ongoing regionalisation of the conflict as a result of the intervention of numerous players, some of which have strongly divergent interests, has significantly complicated past exploratory efforts and made diplomatic solutions impossible to date. The total number of Sudanese citizens who have been forced to leave their homes since 15 April has now exceeded 13 million. The humanitarian situation in Sudan has reached the scale of the Syrian catastrophe between 2015 and 2018. For German and European policy, the relevance of the situation in Sudan arises from the same geographical proximity and the same security interests that prevail with regard to the Sahel region: containing the potential for flight and migration by strengthening state and economic structures and combating non-state armed groups. However, given the focus on the conflicts in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, the Sudan conflict receives little attention in European politics and public opinion.

The Military, Paramilitaries and the Brief Hope of Democracy in Sudan

Despite fears of an armed conflict between the SAF and RSF having already been reported in the weeks leading up to 15 April 2023, the sudden outbreak of violence took many observers by surprise. Almost four years to the day, on 11 April 2019, the current opponents, al-Burhan and Hemedti, were jointly involved in the overthrow of Sudan’s long-term ruler Omar al-Bashir. When a transitional government was agreed upon in July of the same year under the mediation of Ethiopia and the African Union (AU), both generals were given positions on the eleven-member “Sovereign Council”, which was set to run for a three-year period. In addition to the establishment of this council, chaired by al-Burhan and comprising an equal number of military officials and civilians, the politically unencumbered economist Abdalla Hamdok was appointed prime minister and a cabinet composed of representatives of the old regime as well as new figures was appointed. Democratic elections were scheduled for the end of the 39-month phase, and the media reported on the continuation of the “Arab Spring” or a new wave of it. However, those hopes were frustrated due to another coup in October 2021.

Just two years after the transitional political structures were established, the Sudanese military ended the country’s fledgling democratic experiment and ousted the civilian part of the transitional government under Prime Minister Hamdok. The renewed coup on 25 October 2021 was led by General al-Burhan, who was supported primarily by the SAF, but also by the RSF led by General Hemedti. Following ongoing protests by the civilian population and pressure from abroad, Hamdok was reinstated on 21 November. However, power remained almost entirely in the hands of the military and the balance between the military and civilians that had originally been agreed, failed to be restored. Time and again, the army responded to the continuing large-scale demonstrations using force. This led to the final resignation of the Prime Minister on 2 January 2022. Twelve months later, another agreement was reached for a two-year interim phase under a military government, with a subsequent handover of power to a civilian government.

In the few months leading up to the outbreak of violence in April 2023, tensions within the Sudanese security apparatus steadily increased. The founding of the RSF as an additional armed player two decades earlier and its rise to become an actor on a par with the armed forces proved fatal. The long-simmering question within the security sector about the future primus inter pares escalated when the RSF opposed plans to integrate into the SAF. Specifically, the disagreement arose from the armed forces’ demand for a complete transfer of the RSF into the regular army within 24 months, i.e. during the interim phase, while General Hemedti’s organisation demanded a time horizon of ten years. After both sides had spent days preparing for a direct confrontation, the SAF ordered the RSF to evacuate certain positions in the greater Khartoum area, prompting RSF fighters to attack army facilities. On 17 April 2023, their commander-in-chief, General al-Burhan, declared the organisation of his former ally a rebel group and ordered it to disband.

Territorial Control, Balance of Power and Dependence on Arms Supplies

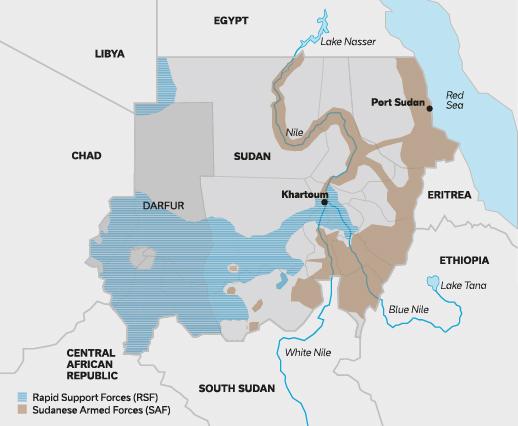

Even after 20 months of intense, nationwide fighting, neither of the two main players has been able to clearly gain the upper hand. The SAF, whose total strength is estimated to be at least 200,000 men, control almost the entire sparsely populated northern part of the country, including the Nile river valley from the Egyptian border to the embattled cities of Khartoum and Omdurman, as well as the entire coast of the Red Sea with the important harbour city of Port Sudan, which serves as the provisional seat of al-Burhan’s military government. The border areas with Eritrea in the east and Ethiopia in the south-east are also largely controlled by the SAF. The populous south-west and large parts of the border with South Sudan, as well as the south of the Darfur region and large parts of the border region with Chad, are controlled by the RSF, which is often said to have 100,000 troops.

The RSF emerged in 2013 from a militia encompassing members of nomadic Arab tribes, known as the Janjaweed, which had already gained notoriety as an auxiliary force of the regular Sudanese security forces during the Darfur conflict from 2003. Although the RSF are primarily equipped and trained for infantry combat in urban centres and operations in desert and semi-desert terrain and do not have an air force of their own, since April 2023 they have proven to be on par with the SAF and have inflicted some heavy defeats on them. The strength of the RSF can mainly be attributed to its homogeneity and the large contiguous retreat areas in the west and south-west of the country, its extensive combat experience, high degree of mobility and relatively good armament. A large number of RSF members were already experienced in combat due to their deployment in the Yemeni civil war from 2019 and their participation in the civil war in Libya when the war in Sudan broke out in April 2023. The RSF’s good relations with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which orchestrated the deployment of tens of thousands of Sudanese fighters in Yemen, and its contacts with Libyan General Haftar, stem from its operations in these two countries. In 2019, the UAE had already provided the RSF with more than a thousand off-road vehicles that were converted into weapon carriers and proved to be essential for the organisation’s mobile warfare.

However, at the outset of the war, the SAF controlled the much larger share of heavy equipment, the air force and the very strong domestic arms and ammunition production, which had developed into the third largest arms industry in Africa in recent decades with manufacturing capacities for infantry weapons, artillery systems and armoured combat vehicles. The country’s defence factories concentrated in the Khartoum area were therefore heavily contested, especially in the summer of 2023. Both warring parties are now de facto dependent on the supply of arms, ammunition and equipment from abroad. Modern types of weapons that provide an operational advantage are particularly sought after, especially drones and anti-aircraft systems. The SAF appear to receive most military support from Egypt, but other states also provide weapons and material of high operational importance. Iran, for example, is said to provide modern drone technology. The UAE is the most important military supporter of the RSF, even though this is regularly denied by the government. Numerous reports indicate that modern weapon systems of various origins, including drones, multiple rocket launchers, man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS) and anti-tank missiles, are being supplied by the UAE to Sudanese paramilitaries. This is done to a lesser extent via routes from Uganda and South Sudan, but mainly via supply routes through Libya and Chad, with aid flights and humanitarian facilities probably being used as cover in some cases. After the fall of the Bashir regime and into the early stages of the war, Russia had good contacts with both General al-Burhan and General Hemedti. Support for the RSF by irregular fighters from the Wagner Group appears to have declined significantly in the aftermath of the attempted coup by Yevgeny Prigozhin in June 2023. In the meantime, Russia, along with Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iran, stands firmly behind the SAF and General al-Burhan. Since September 2023, selective operations by Ukrainian special forces against Wagner Group units, renamed Africa Corps, have been reported.

Fig. 1: Territorial Control of the Conflict Parties

Interests and Policies of Key External Players

Egypt

For Egypt, the conflict in Sudan poses a serious threat to its stability and security. In view of the situation in Libya and the war in Gaza, Egyptian President al-Sisi is keen to avoid further escalation on the country’s southern border at all costs, especially as the conflict with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) continues to intensify. The influx of Sudanese refugees is putting a strain on Egypt’s already limited resources and exacerbating existing problems on the housing market, in healthcare and in access to educational institutions. As a result, the Egyptian government has adopted restrictive measures and closed Sudanese refugee schools on the grounds that they are not part of the public school system. Although humanitarian aid is being provided, Sudanese refugees are confronted with hostility from parts of the Egyptian population. This is fuelled by misinformation and economic fears. Media reports and public statements repeatedly portray Sudanese refugees as an additional burden on the struggling economy and the weak social system, leading to tensions with the host community. What is more, misinformation often circulates about disproportionately high benefits for and unfair job allocation to refugees. International aid organisations in Egypt, as in Sudan, face considerable difficulties due to bureaucratic hurdles, particularly lengthy approval procedures and security concerns, and in some cases can only operate to a limited extent.

Saudi Arabia

The government in Riyadh is primarily interested in stability in Sudan, and especially after recent experiences following the Tigray war, it fears a sharp increase in refugee movements via the East African migration route along the strait between Djibouti and Yemen or directly via the nearby Red Sea coasts. It is therefore hardly surprising that Saudi Arabia is supporting the government camp under al-Burhan, whose armed forces control the entire Sudanese part of the Red Sea coast opposite the Arabian Peninsula. The fact that the Kingdom is no longer on the side of the RSF, even though they served as an important military ally in the Yemeni civil war, also reflects the drifting apart of the former close partners Saudi Arabia and the UAE. It is not only in Sudan where these countries have increasingly come into conflict with each other in recent years. Paradoxically, this positioning puts Riyadh behind the same party that is also supported by its arch-enemy Iran. This is because the Gulf monarchy has no interest in Russia or even Iran gaining a military foothold on the Sudanese coast.

Russia and Iran

Russia’s policy towards Sudan has for years been aimed at finalising an agreement to establish a naval base on the Red Sea, similar to the one in Tartus, Syria, on the eastern Mediterranean coast. After a series of exploratory talks with other neighbouring countries failed, Russian and Sudanese sources reported a preliminary agreement in February 2023. The military, including both of today’s opponents, had agreed at the time, but referred to the final approval by the civilian government to be elected later. Russia’s clear positioning on the side of al-Burhan can above all be explained by the clear prioritisation of the long-awaited naval base near the harbour city of Port Sudan. In recent months, there have been reports that the Iranian government is also interested in a naval base or at least permission to permanently station a larger naval unit in Sudanese waters. Apart from Iran’s fundamental strategic interests in gaining a foothold on the coast facing its Saudi arch-enemy, the security policy developments in the Red Sea following Hamas’ attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 are likely to have dramatically increased Tehran’s interest in a maritime presence there.

United Arab Emirates

Due to its extensive arms supplies, the UAE is by far the most important ally of the RSF. The involvement in the war in Sudan is a continuation of Abu Dhabi’s policy of the past decade and aims at expanding its own influence on the Arabian Peninsula and in East Africa through economic investment and support for non-state armed groups. In recent years, the UAE has invested more than six billion US dollars in Sudan, particularly in the harbour infrastructure of Port Sudan. Apparently, Abu Dhabi is counting on the RSF gaining the upper hand militarily and taking possession of the Sudanese coastline in the near future. Another strong interest of the UAE lies in Sudan’s role as the third largest gold producer in Africa. For years, numerous mines have been controlled by the RSF under General Hemedti, who, as the most important gold trader in his country, is one of the central suppliers for markets in the Persian Gulf. The fact that the UAE is making major profits from the gold trade with a party to the conflict should be addressed more strongly by the EU.

Ethiopia

The security of the economically significant Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, located just 45 kilometres from the Sudanese border, is of central interest to the Ethiopian government. The construction of the dam on the Nile was a serious point of contention between Ethiopia and Egypt for two decades. Egypt fears becoming heavily dependent on Ethiopia for the country’s drinking water supply. So far, Sudan has adopted a balancing and neutral position. Addis Ababa is now keeping a close eye on whether and to what extent the balance of power is shifting in the constellation of these three states. Against this background, Ethiopia is seen as a supporter of Hemedti, the opponent of the Egyptian protégé. The government in Addis Ababa has been regularly accused of providing at least indirect military support to the RSF. From the Ethiopian perspective, another security concern is to avoid a resurgence of the border conflict over the al-Fashaga region. This fertile agricultural land was the subject of a compromise solution (“soft border”) in 2008, whereby the Sudanese claim was recognised, but Ethiopian citizens were allowed to continue farming there. In the wake of the Tigray conflict, however, armed militias not under the control of the central government in Addis Ababa have articulated a full claim to ownership.

Chad

The United Nations arms embargo on the Darfur region in western Sudan, which has been in place since 2005, has been unable to prevent the main route for arms supplies from Chad from leading into this very region. Numerous Chadian citizens, almost exclusively ethnic Arabs, also fought in the ranks of the RSF from the outset. This, in turn, harbours the risk of a spillover of the conflict onto Chadian territory. The de facto president of Chad, Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno, and a large part of the country’s elite belong to the Zaghawa ethnic group, which is largely based in Darfur, Sudan, and is fighting against the Arab groups. With some 900,000 Sudanese refugees, an estimated 88 per cent of whom are women and children, having arrived in the eastern regions of Chad over the past 18 months, the country, which is one of the poorest in the world, also has a considerable humanitarian burden to bear.

South Sudan and Uganda

The southern neighbours Uganda and South Sudan are also heavily affected by the refugee movements. There are currently an estimated 500,000 Sudanese refugees in South Sudan, which until 2011 was part of their own country of origin. Prior to the outbreak of the war, there were around 55,000 Sudanese refugees in Uganda. A further 170,000 people have arrived since, but have not been granted official refugee status due to reservations on the part of the Ugandan authorities. A similar danger of being drawn into the conflict, as seen in Chad, also exists for South Sudan. South Sudanese citizens have joined both the RSF and the SAF. Furthermore, the war in Sudan is jeopardising the export of South Sudanese oil, 100 per cent of which is exported via Port Sudan accounting for some 90 per cent of South Sudanese state revenue. Apart from the supply routes for the RSF via Libya and Chad, there are repeated reports of supplies and support networks in South Sudan and Uganda.

A number of states, including the People’s Republic of China, Turkey, Israel, Kenya and Qatar, also have considerable (security) policy and economic interests in Sudan and therefore maintain relations with both sides without taking a clear stance.

Peace Talks – Many Initiatives, Little Hope

Since the outbreak of the war, there have been various mediation efforts to achieve a temporary or permanent ceasefire or to initiate a structured peace process. The talks in Jeddah mediated by Saudi Arabia and the US, which began in May 2023 and ultimately led to talks in Geneva in August 2024, attracted a great deal of attention. In addition to the hosts – the US, Saudi Arabia and Switzerland – Egypt, the UAE, the AU and the UN took part as observers. This round of mediation efforts also ended without any substantial results. The SAF had withdrawn their participation, while the RSF participated with a small delegation after initial hesitation. It is worth noting that the observers Egypt, UAE and AU all have experience from their own exploratory initiatives, which at times ran in parallel. The AU alone has tried to initiate substantive talks in three different formats but failed, just like the East African regional organisation Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) with its IGAD Quartet on Sudan.

While criticism is often levelled against the plethora of negotiation formats and the low level of coordination, the main obstacle to a real peace process, or even just temporary ceasefires, is the lack of willingness to negotiate or compromise on the part of the two main parties to the conflict. The high level of influence exerted by external players in the conflict has significantly complicated the framework conditions for a political solution. Relying on their regional alliances and external support, the SAF and RSF leaderships seem to believe that they can significantly improve their respective positions on the battlefield. In this context, it is questionable if and to what extent they still act independently in their decision-making or whether they have already become dependent on their external allies when it comes to the question of “negotiations versus continuation of the fighting”.

Two prerequisites are regularly cited for the success of future peace initiatives: on the one hand, the supply of weapons to the warring parties from the outside ought to be stopped and, on the other, the external allies of the two opponents would have to force them to the negotiating table. In addition to Egypt and the Gulf states, Turkey and the US, in particular, are seen as potential mediators and relevant players with sufficient influence.

Human Rights Violations on an Almost Unimaginable Scale

Given that a large part of the fiercely contested zones are located in urban areas, the war in Sudan has been characterised by a very high number of civilian casualties right from the start. Half of the population has fled the capital Khartoum. According to the UN, more than 13 million people are currently displaced as a result of the fighting over the past 18 months. Of these, 10.7 million are considered internally displaced persons (IDPs); 2.3 million Sudanese citizens have sought refuge outside their country. Since the start of the conflict, more than 20,000 Sudanese have lost their lives, although some sources estimate significantly higher numbers. Around 25 million people, about half of Sudan’s population, need humanitarian aid. The scale of this humanitarian disaster now exceeds that of the Syrian refugee crisis eight years ago. Recently, representatives of European aid organisations spoke of a hunger crisis of historic proportions and the UN has identified the worst famine in more than 40 years – prices for staple foods in Sudan have recently risen by up to 200 per cent compared to the previous year. Both parties to the conflict have already deliberately caused food shortages in order to use hunger as a weapon against parts of the civilian population.

Ethnically motivated atrocities and targeted killings of members of non-Arab population groups also regularly occur in Sudan. Continuous ethnic cleansing is reported above all from the Darfur region. In November 2023 alone, more than 1,000 civilians were killed there, mainly from the Masalit ethnic group. In addition, the warring parties are deliberately destroying supply infrastructure, looting and pillaging, which leads to large-scale flight and displacement and in some cases to the outbreak of epidemics, such as cholera. The vast majority of the Sudanese population no longer have access to adequate healthcare. According to reports, 70 per cent of hospitals are no longer functional. Other crimes against humanity include the use of torture and the systematic use of rape, sometimes of minors, as a weapon. The speed and scale of the humanitarian catastrophe in Sudan as well as the high risk of it spreading to the entire region are now being mentioned in the same breath as the wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Syria.

Outlook and Implications for German and European Policy

Even if the resources of German and European politicians were not absorbed by the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and the political will for engagement in the Horn of Africa or for a stabilisation mission in Sudan were present, many questions would still remain. Following the disastrous results of stabilisation efforts in Afghanistan and the Sahel, all concepts for interventions aimed at building peace, combating the causes of displacement and maintaining or establishing state structures continue to be under scrutiny. Although the political will is there and commitments have been made, Germany does not currently participate in EUNAVFOR Aspides as planned due to its very limited military resources, even though the mission aims to protect vital German interests. The EU mission, deployed since February 2024, is tasked with protecting international shipping in the Red Sea from attacks by the Yemeni Houthis. In any case, the question of German involvement in Sudan does not arise in Berlin beyond the assumption of costs for humanitarian aid and participation in diplomatic initiatives.

In the diplomatic sphere, Germany plays an important role bilaterally or within the framework of the EU, despite its very limited direct influence on the two main parties to the conflict, and should endeavour to expand this role. In light of the current migratory pressure on Europe’s borders, it is in German policy makers’ objective interest to contain the humanitarian crisis in Sudan and counteract further destabilisation of the entire region. If it is not possible to ensure adequate care for the internally displaced persons within Sudan, there is a risk of a wave of refugees heading towards Europe on the scale of 2015. It was only recently reported that 60 per cent of the people in the refugee camps in Calais, France, are already Sudanese citizens. In view of the population development and migration potential in the countries of the Horn of Africa, Europe cannot afford to allow another neighbouring region to descend into chaos. When compared to the refugee and migration scenarios, the European states’ lagging behind in the systemic conflict with Russia and China in that region and the scenario of Islamist terrorist organisations infiltrating the Sudanese vacuum, almost pose the lesser security policy challenges.

– translated from German –

Steffen Krüger is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Egypt office.

Gregory Meyer is a Research Associate at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Regional Programme Security Dialogue for East Africa based in Kampala.

Nils Wörmer is Head of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung’s Regional Programme Security Dialogue for East Africa.

Choose PDF format for the full version of this article including references.