Energy in transition

Greece's energy landscape has been undergoing a metamorphosis in recent years: until now, Hellas has been heavily dependent on energy imports. With the exception of the only deposit of crude oil and natural gas so far in exploration near the island of Thassos in the North Aegean, which nonetheless covers only a minimal share of the country’s needs, crude oil, petroleum products and natural gas represent more than 20% of all imports of Greece. Until 2019, electricity production was dominated by lignite. With a share of more than 30%, Greece was thus among the laggards when it came the implementation of environmentally friendly policies: the development of renewable energy resources was rather restrained, despite Greece's comparative advantages (favorable solar and wind conditions).

Since 2019, however, the government led by Nea Dimokratia (EPP) has been pursuing a new, ambitious environmental policy: at the UN Climate Summit in 2019, Prime Minister Mitsotakis declared that "the share of renewable energy resources in total demand should increase to 35% by 2030" - a significant uptick from the 15% at that time. He also set the target of "decommissioning all -now increasingly unprofitable and costly- lignite-fired power plants by 2028". Meanwhile, Greece is also holding a regional leadership role on environmental protection at the international level: at the invitation of the Greek Prime Minister, the heads of state and government of nine southern EU members signed in September 2021 the "Athens Declaration on Climate Change and the Environment in the Mediterranean"; a declaration to recall promises to promote environmentally friendly measures and strengthen cooperation among Mediterranean neighbors. Greece is becoming a pioneer and a leading nation in environmental protection and renewable energy development.

In parallel, however, the country's foreign and energy policy is also focusing on transitional technologies such as the further development of fossil deposits (oil, natural gas) in the Greek seabed. Greece thus joins a growing group of states in the Eastern Mediterranean that have intensified their efforts in this regard in recent years: Israel, Egypt, the Republic of Cyprus, Lebanon, but also Turkey are among them. At the same time, Greece is strengthening its role as a hub for the storage and transport of natural resources by actively participating and taking initiatives in projects to build pipelines, expand LNG terminals and lay electricity cables.

In this context, the last few years have shown how difficult it is to exploit the energy resources in the bottom of the Eastern Mediterranean (EastMed). Besides the technical hurdles, it is above all the political circumstances that make cooperation and joint extraction of oil and gas difficult.

EastMed: The treasures of the seabed and the difficult sharing of profits

As Eastern Mediterranean is commonly referred to roughly half of the Mediterranean Sea east of Libya and Italy to the coasts of the Middle East (Levantine Sea). It is one of the cradles of human civilisation and is known worldwide for its rich and "turbulent" history. It is a region characterised by different cultures and religions, its idyllic beaches, its mild weather and good food.

Next to the above, it is in recent years the economic importance of this region, which has developed into an energy hub of European and global significance, which draws attention. Since the discovery of the Tamar gas field by Israel in 2009, several countries in the region have been competing to discover and exploit its resources hidden under the seabed (mainly Israel, Egypt and the Republic of Cyprus).

Crucial to the exploration, discovery, exploitation and transport of energy resources to Europe as well as other regions is the establishment of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) between the states of the region in EastMed region. These form the basis for responsibilities for exploration and subsequent economic exploitation. The Republic of Cyprus has worked to conclude agreements with Egypt (2003) and Israel (2010). This was preceded by an agreement with Lebanon (2007), which was never ratified by the Beirut parliament due to objections to the Nicosia-Tel Aviv agreement. After the recent historic agreement between Israel and Lebanon (October 2022) on the delimitation of their EEZs, which paves the way for the exploitation of the important Karish field between the two countries, the way of a settlement between Cyprus and Lebanon is more open (albeit taking into account the prior agreement with Syria required by the latter). This is, however, where the agreements end and the problems begin:

The biggest challenge in the field of energy production in the Eastern Mediterranean is the Cyprus question. After the Turkish invasion in 1974 and the occupation of one third of the island since then, the lack of recognition of the Republic of Cyprus by Turkey and the failure of all peace talks on the reunification of the large island in the Eastern Mediterranean make it difficult to implement the proposed projects to exploit and deliver these resources to Europe. An agreement between the two sides and the Turkish Cypriot community in the north of the island looks impossible so far. The next few months will show whether the newly elected president Nikos Christodoulidis can initiate a process of rapprochement. A second major obstacle are the Greek-Turkish relations. The two countries' views on the issue of setting EEZs are divergent, with Turkey seeking balance through a number of other issues (Turkey is trying to bring other issues to the negotiating table that Greece opposes, such as the maritime borders, demilitarisation of the Greek islands, etc.). The fact that Turkey has not acceded to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982) further complicates the situation.

In this context, the Libyan issue complicated the situation: In November 2019, Turkey signed a memorandum with the Libyan Government of National Accord (based in Tripoli), defining their EEZs; the implementation of this agreement could nonetheless set the region on fire. On the one hand, because this (in violation of UNCLOS) essentially ignored the international legal impact of major Greek islands such as Crete and Rhodes (which, of course, is expected of Turkey, which, as mentioned above, has not signed and ratified UNCLOS, while Libya has signed but not ratified the Convention). On the other hand, Libya's interim government does not have the authority to conclude such international agreements. Greece, Cyprus, Egypt and Israel, as well as a large part of the international community (EU, US, Germany, etc.) have raised both legal and political objections. Nine months later (October 2020), Greece and Egypt signed an agreement on the mutual (partial) delimitation of their EEZs, effectively calling into question the agreement between Turkey and Libya. Shortly before that (in June 2020), Greece signed an EEZ delimitation agreement with Italy; thus adding another piece to the puzzle of legally securing the rights of the Eastern Mediterranean states. Finally, the political agreement between Greece and Albania on the joint referral to the International Court of Justice in The Hague on the issue of the delimitation of their EEZs is worth mentioning. However, the signing of the corresponding contractual agreement is still pending.

It was in this complex and constantly evolving diplomatic environment that the EastMed gas pipeline project was developed. This project was the result of close cooperation between Greece, the Republic of Cyprus and Israel and aimed to transport natural gas from the Leviathan (Israel) and Aphrodite (Cyprus) fields to Europe via Crete, mainland Greece and Italy (via connection to the Poseidon and IGB pipelines). It is an enormous project with major technical challenges (much of the 2,000 km route is in an area of great sea depth and difficult geological conditions) and a high cost of over €6 billion. The EastMed pipeline would be able to supply the European market with 10 billion cubic metres of natural gas. The agreement between the three countries was signed in January 2020, but the project faces significant difficulties: As already mentioned, it is a technical project that is very costly. The construction also effectively excludes Turkey, while the inclusion of the Republic of Cyprus brings the unresolved Cyprus problem into the equation. Turkey has repeatedly voiced its objections to this project (recall that the Turkish-Libyan memorandum was signed at a time when the EastMed plans were being developed). At the same time, Turkey acts as an energy hub for the region via the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and Turkstream. To make matters worse, the US reportedly withdrew its original support for this project in early 2022, citing environmental reasons. However, Turkey's exclusion from this project and the high economic risks are likely key contributing factors to this decision.

And then came war in Ukraine

Then, war came back to Europe. The Russian attack on Ukraine not only brings death, misery, destruction and economic devastation, but also poses a fundamental challenge to the EU in terms of energy supply and security. The dependence on Russian oil and gas had to be ended quickly. Despite the different energy models in the EU member states, the need to decouple from Russia and to procure the resources needed for European industry, economy and society from other countries can become an opportunity. In this context, projects that previously seemed unrealistic are again on the table. The debate on the importance of the EastMed pipeline has already restarted. Despite serious concerns and doubts about the technical challenges around EastMed, the project could be an alternative; bearing of course in mind the EU's goals of gradually reducing the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix. In any case, the EastMed pipeline could help supply Europe with crucial amounts of energy. In order to maintain EastMed as a realistic plan, talks are already underway to change the pipeline route: the Egyptian side has reportedly proposed to Greece as early as 2021 to bypass Cyprus and pump the natural gas from Israel overland to Egypt and from there to Crete. More realistic, however, is the prospect of developing LNG terminals to supply Europe from deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus/Israel).

The crucial role of Greece

In this rapidly changing environment, Greece aims to become a key hub for Europe's energy supply and security, benefiting, among other things, from the political and economic stability it has enjoyed in recent years. With this goal in mind, Athens has initiated a series of policy measures at both national and international levels:

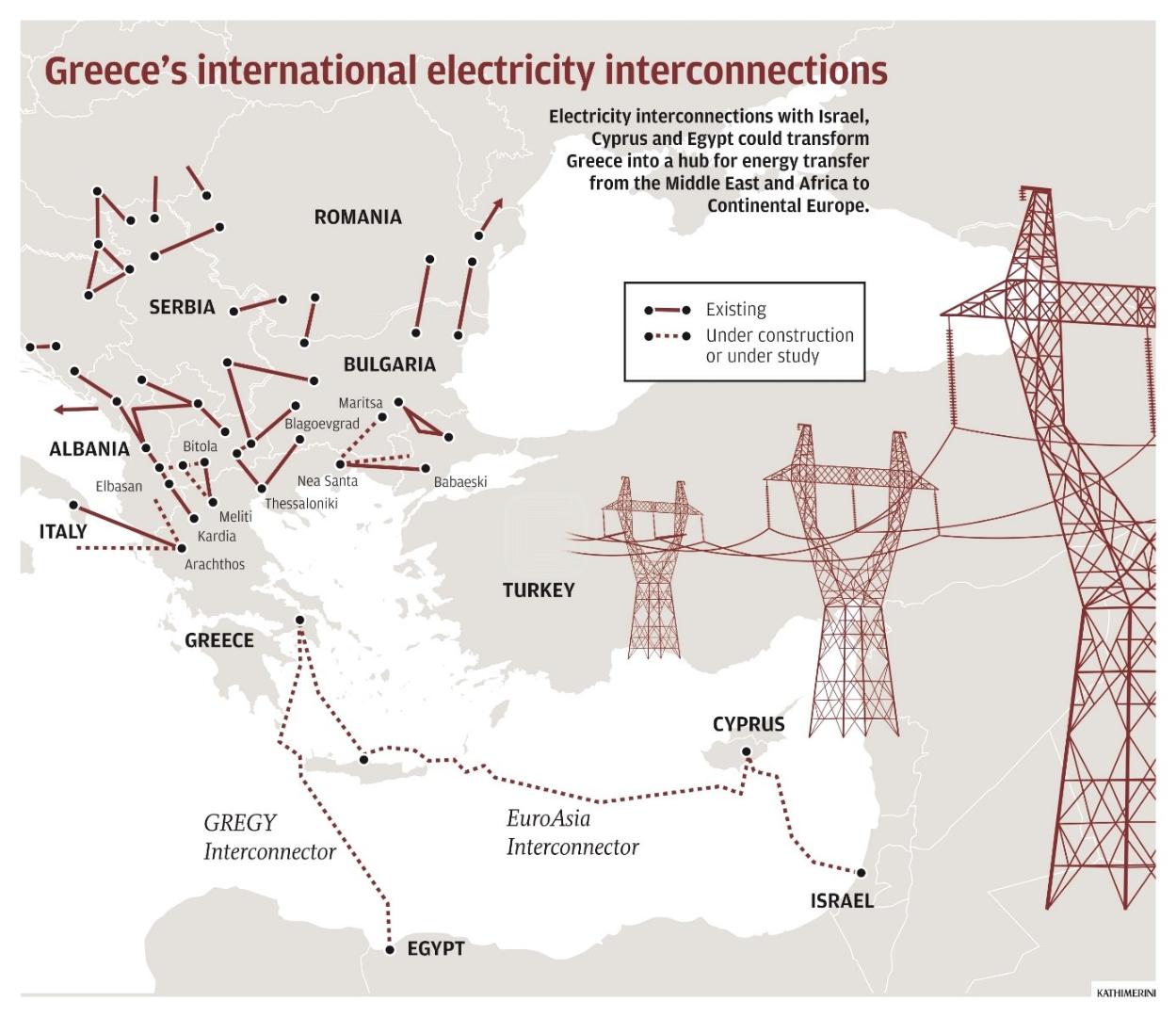

Greece's ambitions to become an energy hub are firstly developing in the electricity sector. This is due to the realisation that securing stable volumes of electricity from renewable and environmentally friendly sources from North Africa and the Middle East will contribute significantly to Europe's energy security, especially in key sectors of the economy such as industry. Greece already has active interconnections with the grids of all neighbouring countries and Italy. In the future, new connections will be developed that would multiply the flow of electricity between these countries. A new connection to the Bulgarian grid is already under construction, while new grids to Italy, Albania and Turkey as well as to North Macedonia are under consideration. However, that is not all: the plans also envisage the transfer of renewable electricity from North Africa and the Middle East to Europe - in particular to Austria and Germany - as announced by Greek Energy Minister Kostas Skrekas. As the Greek Minister of Development and Investment, Adonis Georgiadis, explained, German companies in particular are very interested in investing in the renewable energy sector in Greece.

Two connections play key roles in bringing about this goal: the EuroAsia Interconnector (Greece-Cyprus-Israel) and the GREGY cable (Greece-Egypt).

The EuroAsia Interconnector is a major technical project to lay a more than 1,200 km long power cable from Israel to Greece (Crete) via Cyprus. It is an important Project of Common Interest (PCI) of the European Union that could transport up to 2,000 MW once completed. The strong European interest is also reflected in the significant financial support for the project: 657 million euros have been allocated through the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) and another 100 million euros through the Construction and Resilience Fund. The inauguration of the construction works took place in Nicosia in October 2022; the project is expected to be completed by 2026. Its completion will significantly increase the geopolitical importance of all countries involved, in addition to the very important environmental impact. At the same time, Cyprus will be connected to foreign grids for the first time, enhancing the country's energy supply and security.

The GREGY project is still in the planning phase. It is planned to lay an almost 1000 km long cable from Egypt to Crete, capable of transporting up to 3000 MW of "green energy" from renewable sources. This would have great potential for both Greece and Europe. At the same time, the sovereign rights of Greece and Egypt would be further consolidated on the basis of their agreement on the definition of their EEZs.

However, the main objective of the Greek government is also to promote plans for the exploration and exploitation of natural gas and oil resources of the country. After the initiation of the process some 15 years ago and a period of inactivity between 2014 and 2019, the Nea Demokratia (EPP) government has dynamically advanced the permitting and exploration processes in the Western Greece/Ionian Sea and areas south of Crete. Although there is no confirmed data, modest estimates put the natural gas reserves in the Greek area at between 600 billion and 2 trillion cubic metres. Greece's annual consumption is about 5 billion cubic metres, while the EU's consumption in 2021 has reached about 400 billion. Exploration missions by large international companies (Exxon Mobil, Chevron) have already started: If the procedures go without problems, commercial exploitation could start in 2027/2028. The gains for Greece and Europe as a whole would be immense.

Greece is now investing heavily in expanding renewable energy sources and strengthening their role in the country's energy mix. According to official data from the State Grid Management Authority (ADMIE), in the period January-October 2022, the share of renewables in the energy generation reached 47.1%, surpassing that of fossil fuels. In October 2022, the country was powered only by renewable energy sources for five hours non-stop; a historic day. However, the war in Ukraine has significantly affected the Greek state's ambitious goals for decoupling from fossil fuels and initiated a partial return to lignite: The government decided to extend the lifetime of lignite-fired power plants that were to be taken off the grid in 2023 until 2025; a large 660 MW power plant that was to run on natural gas started operating on lignite in November 2022. For the first time, there is also a focus on the use of previously neglected energy sources: recently, the government announced a framework for the use of geothermal energy. According to the information, a single geothermal field on the island of Milos could cover the energy needs of half of the Cycladic islands.

The war in Ukraine certainly has an impact on the energy policy of Greece, which is trying to reduce its dependence on Russia. Before the war, Greece's dependence on Russia was on par with

the EU average (around 40%); between January and November 2022, this figure fell to below 15%.

Greece replaces Russian energy in the Balkans

The issue of processing and storage of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from third countries and subsequent transport to the Balkans and the EU is also becoming a priority for Greece. Greece's only LNG storage station, on the island of Revithoussa in the Saronic Gulf near Athens, has been working intensively in recent months. Arrivals of LNG cargoes have increased by 70% compared to 2021. At the same time, the station's capacity was recently increased from 225,000 to 360,000 cubic metres with the installation of a mobile storage station. In addition to Revithoussa, the port city of Alexandroupolis near the border with Turkey and the Dardanelles is becoming a strategically important energy hub. In May 2022, Prime Minister Mitsotakis declared the start of the construction of a floating LNG terminal in the presence of EU Council President Charles Michel and the leaders of Serbia, North Macedonia and Bulgaria (which is also contributing financially to the project). The project, scheduled for completion in 2023, is considered crucial for the gas supply not only to the domestic market, but also to Greece's northern neighbours, as far as Moldova and Ukraine itself. The presence of several heads of state and government in Alexandroupolis is a sign that both the Balkan states and the EU as a whole are committed to this project as a means of decoupling from Russia.

Alexandroupolis’s importance will also increase through a new gas-fired power plant, the construction of which was inaugurated by the Greek government in January 2023. This new power plant with a capacity of 840 MW, in which the state-owned electricity company DEI has a 51% stake, will supply Greece as well as Bulgaria, Serbia and North Macedonia.

Greece is thus becoming a dominant energy player in South-Eastern Europe, which will contribute to deepening Greece's relations with its northern neighbours. For example, at the meeting of the heads of state of Greece and Northern Macedonia, Mitsotakis and Kovaczewski, in September 2022, energy cooperation was the main topic of discussion. The need to find solutions to common problems can potentially contribute to the overall convergence between the two countries. Cooperation between Greece and Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary will be strengthened: during the World LNG Conference in Athens in December 2022, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the gas authorities of the four countries to examine aspects of the implementation of the so-called "vertical corridor". This is the possibility of transporting natural gas in two directions between these states, using the existing IGB pipeline between Greece and Bulgaria. Cooperation in the Balkans is not limited to gas, either.

The war in Ukraine is also acting as a catalyst for another project that until recently seemed dead: the Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline. This old project to build an oil pipeline from Bulgaria to Greece had been abandoned in 2011 due to high costs of €1 billion were among the reasons. The needs of Bulgaria, which is highly dependent on Russia for its energy supply, brought this old project back on the agenda. This time the reactivation will take place with one important difference: oil will run in the opposite direction (from Greece to Bulgaria) to supply a Bulgarian refinery on the Black Sea, which meets about 75% of the country's needs.

Conditions for Greece to play its role

Based on the above, Greece has all the prerequisites to play a leading role in energy policy developments in the South-Eastern Mediterranean, which will have significant economic and political implications for the entire European Union. However, the necessary preconditions are:

- rapid progress in the field of hydrocarbon exploration (natural gas, oil) and the discovery of truly large deposits in quantities that justify their costly exploitation.

- further cooperation between Greece and its neighbours. Both in the short and medium term, a close partnership based on political convergence with countries such as Egypt and Israel is crucial for the implementation of flagship projects such as the EuroAsia Interconnector.

- Securing the necessary financial resources is of course an essential parameter for the realisation of plans in the energy sector. A prime example of the importance of securing the appropriate funds is the EastMed pipeline, which is so expensive and technically challenging to build, that it is difficult to realise (despite its importance for Europe's energy security).

- Political stability in Greece has contributed to both the maturation of the plans and the strengthening of international confidence in recent years. The upcoming elections in Greece in spring 2023 should not lead to a reversal of the plans. The conceivable victory of Nea Dimokratia (EPP) would be a guarantee for the predictable continuation of the planned projects.

- Relations with Turkey are a factor that should not be neglected. In particular, in the area of exploitation of energy reserves, the issue of delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zones in the Aegean and south of Crete (see the Turkish-Libyan memorandum and the Greek-Egyptian agreement) should be a European priority. The EU's contribution stems, on the one hand, from the importance that the gas and oil in these areas can have for its energy security and, on the other, from the security implications of this issue.

- The war in Ukraine is proof that any plans at national or supranational level can also be quickly reversed. A thorough examination of all possible scenarios and a high degree of adaptability are therefore necessary to achieve the goals set.

- The development of Greece as an energy hub for the region and Europe should be pursued with due regard to the security interests of the Union, especially concerning new dependencies on third countries. The past has shown that these can have serious consequences. The debate on the involvement of countries such as China in the development of energy infrastructure has started in several European countries and should continue in the light of various plans to be realised in the upcoming years.

Conclusion

The exploitation of energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean will be one of the greatest political, diplomatic and economic challenges for Europe in the medium term. In an ever-changing environment, Greece, a pillar of political and economic stability, can make a significant contribution to meeting the energy needs of the entire region and Europe, both by using its own reserves and by acting as a hub for the supply of environmentally friendly electricity and resources from North Africa and the Middle East. Taking on this role will not only increase the country's importance on the diplomatic chessboard, but is also beneficial for the EU by reducing its dependence on third countries. The Greek energy Odyssey is in full swing; it remains to be seen whether, like in Homer, it will end well.