Past developments

Discussion on the issue of “economic security” first started to attract attention in Japan in December 2020, in a policy proposal issued by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), titled “Recommendations Toward Developing Japan’s ‘Economic Security Strategy.’”1 In these recommendations it was noted that the National Security Strategy of Japan did not clearly address a viewpoint on how Japan would achieve its national interests from an economic perspective, notwithstanding the fact that economic factors are now impacting security, including the changing global power balance, the use of relations of economic dependence for political purposes, the vulnerabilities exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the spread of digitalization. The recommendations went on to define “economic security” as “ensuring Japan’s independence, survival, and prosperity from an economic perspective,” and set out “strategic autonomy” and “strategic indispensability” as its fundamental principles.

The compilation of these LDP recommendations was, in part, a response to various problems that cannot be overlooked and have continued since the 2010 arrest of the Chinese captain of a Chinese vessel that intentionally collided with a Japan Coast Guard patrol vessel, prompting economic coercion from China in the form of rare-earth export restrictions. The recommendations set out a broad range of areas that should be explicitly covered by “economic security” policy, including everything from resources and energy, ocean development, food security, and financial infrastructure, to countermeasures to major infectious diseases, infrastructure export, and involvement in rule-making via international organizations.

Following the issuance of the LDP recommendations, the term “economic security” appeared with increasing frequency in government documents (including the growth strategy, etc.), but the government did not explicitly stipulate its own definition. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, speaking in his first policy speech upon being appointed Prime Minister (October 8, 2021), positioned “economic security” as the third pillar of his government’s growth strategy, stating that “Under a newly established ministerial remit, we will advance our efforts to secure strategic goods and materials and prevent outflows of technology, while we will materialize an autonomous economic structure. We will build a resilient supply chain and draw up legislative bills that promote Japan’s economic security.” In the same speech he also separately identified “realizing a science and technology nation” as the first pillar of the government’s growth strategy, indicating an understanding of the funding of “research and development in advanced science and technology” as something distinct from “economic security,” which was therefore defined more narrowly than in the LDP recommendations, being focused rather on (i) securing strategic goods, (ii) preventing outflows of technology, and (iii) building a resilient supply chain.

Thereafter, the first meeting of the Council for the Promotion of Economic Security, chaired by the Prime Minister was held (November 19, 2021), in which the goals of “economic security” were enumerated as follows: (i) strengthen the autonomy of Japan’s economic structure by making supply chains more resilient and ensuring the reliability of key infrastructure; (ii) work to foster critical technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum, and ensure the superiority and therefore indispensability of Japanese technologies; and (iii) aim to maintain and strengthen the internationalorder based on fundamental values and rules. Assuming that these three broad directions were concurred on among the ministers concerned, this would indicate that a slight change in the scope of “economic security” had occurred from the time of the policy speech.

Following the above-mentioned developments, in February 2022 the government’s bill for the Act on the Promotion of Ensuring National Security through Integrated Implementation of Economic Measures (hereinafter “Economic Security Promotion Act”) was approved by the Cabinet and submitted to the Diet. This Act sets out the challenges for economic security into the three following areas: (i) areas where efforts have already been initiated and will be continued and enhanced; (ii) as initiatives continue to be enhanced, areas that should be addressed as a matter of priority through the formulation of legislative measures; and (iii) ongoing consideration of further issues in anticipation of future changes in the situation. Applicable to (ii) above were the following four new legislative measures: “systems for ensuring stable supply of critical products,” “system for ensuring stable provision of essential infrastructure services,” “system for enhancing development of specified critical technologies,” and “system for non-disclosure of selected patent applications.” The Act was passed and promulgated in May 2022, with phased entry into force thereafter ranging from within six months to within two years. The various necessary budgetary allocations were also implemented at the same time. The Act does not contain a definition of “economic security” and in the course of Diet deliberations the Minister in charge of Economic Security responded that “ensuring the safety of the nation and its people from an economic perspective” is the purpose of “economic security.”

In May 2024, another law to be passed was the Act on Protection and Use of Critical Economic Security Information (hereinafter the “Critical Economic Security Information Act”). This Act institutionalizes the so-called “security clearance” system, which has been identified as being an important aspect of economic security policy. Under this system, as a part of the nation’s information security measures, the government grants access to those who need access to information designated as critical security information held by the government, after first investigating and confirming the reliability of such persons.

In parallel with the above-mentioned development of legislative measures, work was also progressed on the development of economic security policy-related organizations within the government. The National Security Secretariat (NSS) acts as a coordinating body for the Japanese government’s diplomatic and security policies, and in April 2020 the NSS newly established an Economic Security Unit dedicated to economic affairs. Next, in October 2021, Prime Minister Kishida newly established the post of Minister in charge of Economic Security. Following the partial entry into force of the Economic Security Promotion Act in August 2022, the Economic Security Promotion Office was established in the Cabinet Office, and the Minister in charge of Economic Security was positioned as a Minister of State for Special Missions. It is anticipated that these organizational developments will help economic security policies to become more unified and consistent across all government ministries and agencies.

Significance of economic security policy in the current situation

Japan’s economic security policy has thus taken shape as described above, but as the process of formulation of the Economic Security Promotion Act duly demonstrates, its enactment does not in itselfcomplete Japan’s economic security policy. Areas that need to be covered by economic security policy are wide-ranging, and review and revision are constantly required in response to the ever-changing situation.

Although in the first place it is difficult to state that the definition of “economic security” has been set out unequivocally, the essential challenge for any definition is to strike a balance between “economic logic” (the logic of seeking economic efficiencies based on market principles) and “political logic” (the logic of seeking the political value of security, in a dimension distinct from economic efficiencies) from the perspective of national interest. In that sense, it could be seen as nothing more than attaching the label “economic security” to what has traditionally been implemented previously in individual policy areas.

For example, the Japanese government has sought to incentivize the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSMC) to establish a presence in Kumamoto Prefecture in order to expand semiconductor production in Japan and is forecast to provide upward of 1.2 trillion yen in subsidies for the construction of the first and second plants. In addition, the government has already provided 330 billion yen in subsidies to Rapidus Corporation, a company newly established with the mission to realize domestic production of next-generation semiconductors, with this figure expected to ultimately reach a total of approximately 920 billion yen. Total government subsidies earmarked for the support of the semiconductor industry have reached approximately 3.9 trillion yen over the three-year period from fiscal 2021 to 2023. This policy of injecting massive subsidies could also be viewed as an attempt to revive in a new form the former “industrial policy” developed and pursued until the 1980s by the then Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, today’s METI) under the new banner of “economic security.”

Similarly, if looked at with an open mind, many of the policies being advanced as current economic security policy could be said to in actual fact be extensions of previous policies. However, the fact that the Japanese government has reiterated “economic security” as an important policy pillar is significant for three reasons.

First, it is significant as it presents an opportunity to review and restructure conventional policy development in a way that reflects the latest changes in the current situation. The increasingly confrontational relations between the U.S. and China of recent years have provided a major stimulus in this respect. Moreover, it also sends a message internationally that Japan is committed to reviewing and restructuring such policies. On this point, it would perhaps be appropriate to take an even longer historical perspective. Following the end of the war, Japan followed what would become known as the “Yoshida Doctrine,” under which Japan was managed by a pragmatic national strategy. Security was assured on the basis of the Japan-U.S. Security Alliance, and Japan’s national strategy of focusing on the economy while only lightly armed proved to be an effective strategy for the duration of the Cold War. However, the upheaval in the international environment following the end of the Cold War necessitated a review of this national strategy. The aim of the administration of Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone (1982-1987) was to “advocate a final settlement of postwar politics and the realization of Japan as an internationally oriented nation that makes an active external contribution to world peace and prosperity.” This was part of that historical trend. For Japan, it has been a historical necessity to take the initiative in reviewing and restructuring its own policies in the face of the changes in the international environment following the end of the Cold War and, more recently, the rise of China and its actions that diverge from accepted norms.

Second, it is significant as it presents an opportunity to review internal government divisions of responsibilities. Each policy area is divided across multiple ministries and agencies, and it is this dispersed approach that has given rise to inconsistencies and inefficiencies. In particular, in Japan there have been significant challenges in terms of coordination between the organizations with authority over security and those responsible for overseeing economic policy. If these separate organizations could be unified and coordinated under the banner of “economic security,” it could be expected to lead to improved consistency and efficiency in terms of overall policy. This represents a major change when one considers how Japan’s bureaucracy and administrative structures have long been criticized as being vertically structured into siloes. Even when considered from an international perspective, it is rare for a country to have an administrative organization responsible for overseeing economic security policy.

Third, it is significant as it presents an opportunity to raise awareness of “economic security” within private sector companies. Companies are organizations that are essentially profit-seeking in nature, and therefore naturally tend to prioritize “economic logic,” but raising awareness of “economic security”-related risks is important not only from a national perspective, but also for the management of risks by companies. In reality, as discussion over “economic security” in Japan has intensified, an increasing number of companies have newly established a director or department responsible for “economic security.”

By vigorously promoting economic security policies that possess the above-mentioned significance from legislative, institutional, and budgetary perspectives, Japan’s economic security policy has also come to be recognized internationally as a pioneering initiative.

Challenges

(1) Essential challenges

As noted above, the essential challenge for “economic security” is to strike a balance between “economic logic” and “political logic” from the perspective of national interest. “Economic logic” is the logic of seeking economic efficiencies based on market principles, the fundamental idea since the time of Adam Smith being trusted in market functions. In contrast, “political logic” seeks political value of security in a dimension distinct from economic efficiencies. Political value includes such things as security, democracy and human rights.

Although finding a balance is something that can be easily said, “economic logic” essentially pursues efficiency by assuming a win-win game in which rational actors are the players and, in contrast, “political logic” assumes the existence of values beyond economic rationality and, in some cases, values based on irrationality. Finding a balance is therefore a challenge fraught with difficulty that involves fundamental trade-offs.

This is in fact a challenge that has existed for some considerable time. During the U.S.-Soviet Union Cold War era economic relations between the countries of West and East were so small as to be almost negligible, with relations being largely a matter of so-called “high politics” that fell under the category of “political logic.” The “containment” policy of the U.S., developed on the theoretical basis of George Kennan’s “X Article,” was truly a policy in total adherence to “political logic.”

Subsequently, with the end of the Cold War came the assertion that democracy and free-market economics had triumphed in the international community bringing about the “end of history” (Francis Fukuyama), and in turn the balance veered sharply towards “economic logic.” This is because the accession of Russia and China to the World Trade Organization (WTO) was achieved with the support and encouragement of other countries, with it being assumed that the two would be duly incorporated into the Western order. Following “political logic,” the costs associated with security were greatly reduced, instead being enjoyed as economic “fruits.

However, “history” had not come to an end. Authoritarian states remained essentially unchanged, and as it developed economically, China made no attempt to hide its stance of challenging the existing order. It was at this point that the balance, which had swung significantly towards “economic logic” found itself being corrected from the perspective of “political logic,” with “economic security” thus being propelled to become an urgent agenda item.

As described above, Japan’s pioneering efforts in recent years to bring economic security policy into the international spotlight can be understood as a move to recalibrate “economic logic” and “political logic” in a way that responds to changes in the “Grand Narrative.”

Based on such an understanding, it is clear that constant review of economic security policy is required, and such constant review is the essential challenge facing economic security policy. What is more, such a review would of course be by no means sufficient if Japan were to implement it in isolation. From Japan’s perspective, working in cooperation with the countries of Europe, the U.S., and the countries of Asia, the challenge is to ensure that the balance between “economic logic” and “political logic” is always appropriate and in tune to the international situation at any given time. On the other hand, Japan now has increasingly interdependent relations with China in economic terms and cannot escape its geopolitical influence, making it necessary to constantly seek to find a mutually accommodating balance with China. One of Japan’s major essential challenges is how accurately and strategically it can advance such international efforts.

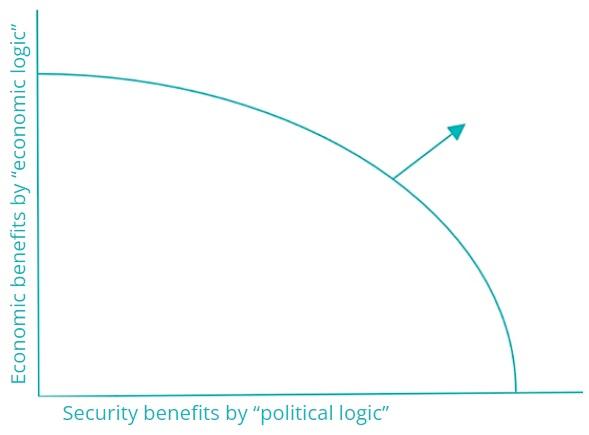

In addition to the above, the challenge of achieving an appropriate balance while also improving the optimum point is also important. If a diagram were to be drawn of the trade-off relationship between “economic logic” and “political logic,” the achievable point of balance is shown on the possibility curve below, but it is also important in policy terms to shift this possibility curve upwards. If it is possible to effect such a shift, both economic and security benefits could be improved.

(2) Urgent challenges

Although in the above figure the aim should be to shift the possibility curve upwards, in reality there can be and, in actual fact, are situations where an achievable optimum point on the possibility curve is not realized, instead remaining inside the possibility curve. From the perspective of at the very least avoiding such a situation and realizing a point of balance on the possibility curve, the following are examples of urgent challenges that could be pointed out.

(i) Relationship between the government and private sector companies

Many of the locations most closely related to economic security are the places of business of private sector companies. It is precisely for this reason that it is essential for the government to share sufficient awareness of the issues with private sector companies if economic security policy is to be implemented appropriately.

A prerequisite is the mutual sharing of sufficient information between the government and the private sector, and while there are both formal and informal efforts already being made at public-private sharing in Japan, there is still room for improvement.

Furthermore, before information can be shared between the government and the private sector, another challenge is to improve their respective information gathering and analysis capabilities. Although efforts are being advanced to enhance the “economic intelligence” functions of the government and for companies to gain a fuller awareness of the status of their own businesses, considerable improvements are presently required on both sides. For example, in the private sector there are more than a few companies that do not have a full understanding of the actual status of their own supply chains. On the other hand, there are some cases where various regulatory information provided by the Japanese government to private companies on the basis of economic security needs, is not as clear-cut as information provided in the U.S. Entity List. Not only does this have an excessively constraining effect on private sector companies, but there are also concerns that it could result in the creation of grey zones that enable lobbying by countries and other entities of concern in terms of economic security.

(ii) Review of critical products and essential infrastructure

Although Japan’s Economic Security Promotion Act makes provisions relating to critical products and essential infrastructure, these are areas where constant review and revision are required, based on the latest developments. One example of such a revision being necessitated occurred on July 4, 2023, when the Nagoya United Terminal System (NUTS), in operation at five container terminals and centralized control gates at the Port of Nagoya, was subjected to a large-scale cyberattack that resulted in a three-day stoppage of all operations. In response to the incident at the Port of Nagoya, on January 30, 2024, in the sixth meeting of the Council for Promotion of Economic Security, the Prime Minister stated, “In terms of essential infrastructure, in light of the incident last year at the Port of Nagoya, it is necessary to add general port and harbor transportation businesses to the businesses covered by the Economic Security Promotion Act,” and issued instructions that, “A bill revising the Economic Security Promotion Act to add general port and harbor transportation businesses to essential infrastructure should be promptly formulated, and the government should coordinate with the ruling parties to accelerate preparations to submit the revision bill to the current regular session of the Diet.” As a result of this process, the Act to Partially Amend the Economic Security Promotion Act was passed in May 2024, in which “general port and harbor transportation businesses” were added to the businesses covered by the essential infrastructure system and is scheduled to enter into force within 18 months. While an ex post facto review of such incidents is unavoidable in practice, an appropriate proactive review of critical products and essential infrastructure should be conducted in advance as far as it is possible to do so.

(iii) Non-disclosure of selected patent applications

One of the pillars of the Economic Security Promotion Act is the establishment of a system for non-disclosure of selected patent applications. This is something that has already been introduced in many other countries and is a system that was also long awaited and anticipated in Japan.

Although the recent establishment of the system represents an important step, it is designed in such a way that even if an application is recognized as sensitive technical information for national security purposes, there is still an option for the applicant, a private company, to make a decision to withdraw the application itself, leaving concerns that this could become a major problem depending on the actual operation of the system. Operational innovations and future amendments to the system also therefore need to be considered.

Conclusion

While Japan’s economic security policy has been pioneering in some respects, even from a global perspective, issues nonetheless remain and there are areas where improvements are still needed. It will be necessary for Japan to revise policies accordingly, while also referring to developments and initiatives in other countries.

For example, in the Republic of Korea (ROK), the Special Act on the Promotion of National Strategic Technologies was enacted and promulgated on March 21, 2023. It has been observed that efforts to manage and protect knowledge and information related to the national strategic technologies covered under the Act are more thoroughly stipulated and effective than Japan’s policy, and there are elements that Japan would be well advised to refer to in the future. Furthermore, so-called investment screening has yet to be introduced in Japan, and although the government is attempting to enhance effectiveness by managing the transfer of technology itself, further study is likely to be required depending on the status of other countries’ efforts.

In any event, as long as the essential task of economic security is to realize an appropriate balance between “economic logic” and “political logic,” it will remain a never-ending policy challenge that could be likened to the “Rock of Sisyphus” in Greek mythology. It is precisely because these are open-ended challenges that we must accurately understand their essential nature, and formulate and implement policies accordingly. Whether or not we can indeed do so is our own fundamental challenge.

About the Author

Shigeaki SHIRAISHI is former Senior Research Fellow and Director of Research Center for Economic Security at Nakasone Peace Institute on loan from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

He graduated from the University of Tokyo with a B.A. in Law in 1988. He completed graduate studies at Princeton University with a Master in Public Affairs in 1994.

He joined the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) in 1988. He has held posts including Director of the Information and Research Division, Trade Policy Bureau; Senior Fellow, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (concurrently OECD consultant and IEA consultant); Director of the Service Affairs Policy Division, Commerce and Information Policy Bureau; Counsellor, Cabinet Secretariat; and Vice President, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.

The views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this report are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the view of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, or its employees.